Artificial intelligence is making it easier to describe smells

Most people don’t have the right words to describe what they’re smelling. Though humans can distinguish about a trillion odors, our vocabulary is limited. Terms like “fruity” or “musky” are not only imprecise, but also colored by cultural bias. Unlike with other senses—hearing, sight, touch, and taste—we have trouble agreeing on universal terms for smells.

Most people don’t have the right words to describe what they’re smelling. Though humans can distinguish about a trillion odors, our vocabulary is limited. Terms like “fruity” or “musky” are not only imprecise, but also colored by cultural bias. Unlike with other senses—hearing, sight, touch, and taste—we have trouble agreeing on universal terms for smells.

Now, an IBM study recently published in Nature suggests a promising solution to augment our smell vocabulary. Researchers led by computational neuroscientist Guillermo Cecci used artificial intelligence to create an algorithm that translates fuzzy descriptive words to their molecular equivalent, and vice versa.

Odor wheel

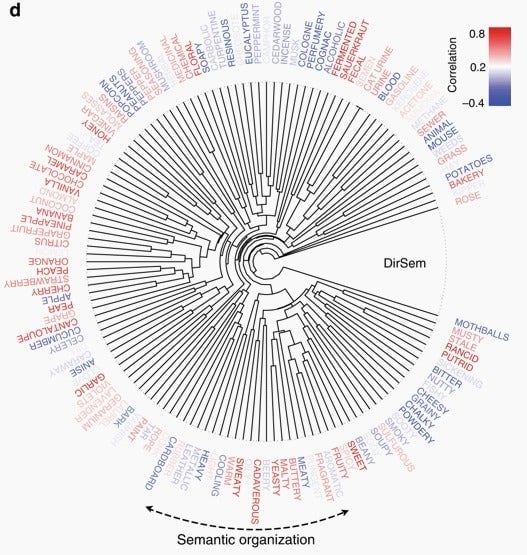

Researchers summarized their findings in an “odor wheel” that takes the most commonly used English words to describe scent, and arranges them in associative order. For instance, “vanilla” is adjacent to “chocolate” and “caramel” on the wheel, signaling to perfumers and chemists that when someone wants a vanilla candle, they likely won’t mind hints of caramel or chocolate.

“Now we do not need to profile a certain smell across a large set of descriptors,” explains Cecci. “In a sense it is similar to a color wheel… we can now mathematically determine nuances or close alternatives to a desired odor.”

The odor wheel also shows that some descriptive words translate to molecules better than others. Words written in red, including “sweaty” or “cadaverous,” are understandable to chemists, while those in written blue, like “soapy” or “cardboard,” are problematically vague.

But the graphic could use an information designer’s touch. Several words in the odor wheel, such as “methane” and “ammonia,” are so faded that they’re barely legible. Confusingly, this means that they fall in the middle of the spectrum and not that they’re unclear, as faded words might suggest. We recognize the smell of ammonia more readily than that of potatoes, but on the wheel the former is faded and the latter is blue. (Paging IBM’s legion of design experts.)

AI to the rescue

Ultimately, the goal is to improve the human capacity to talk about smell, an ability that has languished in part because we prefer sanitized environments and tend to extinguish unpleasant odors, explains Cecci. In the same way machine learning is being used to scan books or process surveillance information, IBM is using it to expand linguistic abilities pertaining to smell.

IBM’s breakthrough research is helping to untangle the mysteries of the human olfactory system, but more work needs to be done to create a universally useful odor wheel. Cecci and co-author Pablo Meyer say the study should be conducted in other languages because our perceptions are always affected by cultural factors.

In theory, IBM’s algorithm can shorten the typically onerous manufacturing process involved in creating lab-made perfumes and odorants. Our limited vocabulary makes the job of creating scents laborious and expensive. As it’s been for centuries, perfumery is still largely a trial-and-error (or sniff-and-sample) endeavor. It takes trained “noses” months, if not years, to arrive at the desired scent.

Healthcare implications

Cecci points out that the healthcare industry can benefit from smell research, too. For example, a more precise odor vocabulary can help doctors diagnose neurodegenerative diseases faster. Adults who fail a simple sniff test are twice as likely to develop dementia, according to a study published last year in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

The problem is that the language around scent has lacked an objective component. “We now think that given our AI-based method to semantically analyze odor perception, we will be able to work towards developing and finding signatures that can indicate disease,” says Cecci.