Growth in China’s housing prices is slowing. That should be a good thing, but it’s not

After strong growth this year, commercial housing price inflation may finally be cooling down in China’s biggest cities. New home prices rose only 0.6% on the previous month, down from 0.7% in September. That drop was more marked in big cities. In Shanghai, October prices grew only 0.9% on the prior month, after climbing 1.6% in September.

After strong growth this year, commercial housing price inflation may finally be cooling down in China’s biggest cities. New home prices rose only 0.6% on the previous month, down from 0.7% in September. That drop was more marked in big cities. In Shanghai, October prices grew only 0.9% on the prior month, after climbing 1.6% in September.

That’s probably because the government has been taking steps (such as requiring a 70% down payment and charging a 20% capital gains tax on the sale of second homes) to reduce demand in big cities. With all the talk of a bubble, surely slowing price growth is a good sign?

It should be in theory. For one, money spent on a down payment is money that’s not going toward other forms of consumption, which are needed to rebalance the Chinese economy and shift away from investment-led growth.

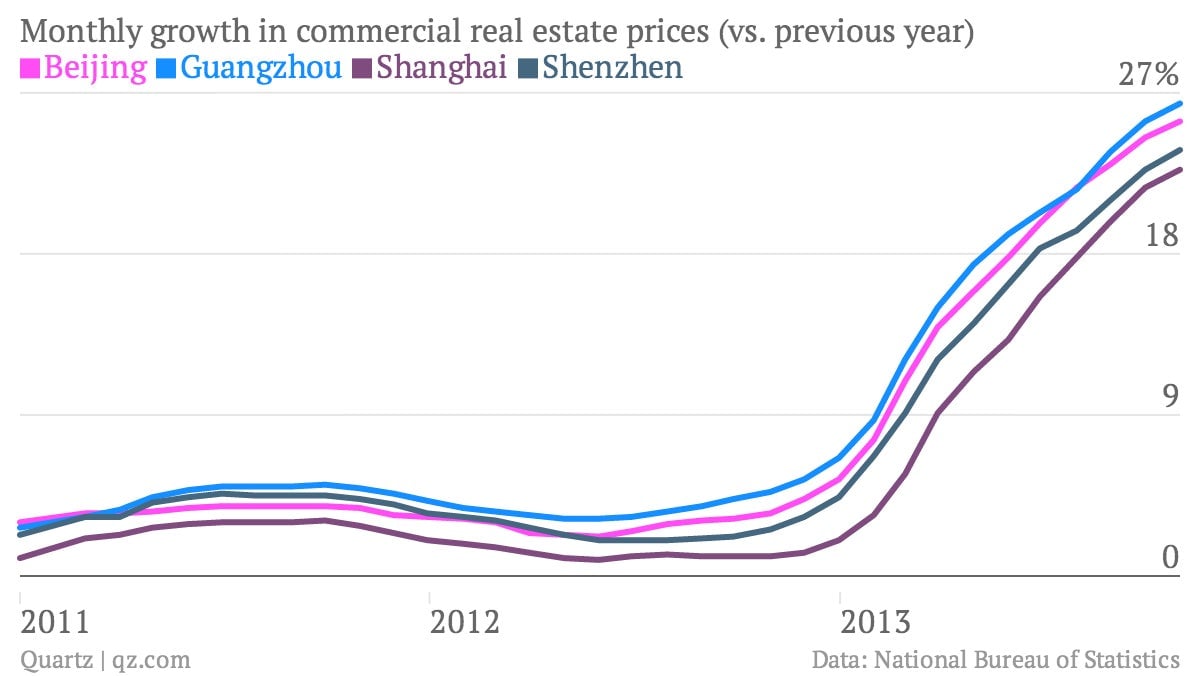

But though the new government measures are making it harder to buy homes in the big cities, they’re unlikely to change market dynamics everywhere else. First-tier city prices are still sky-high by annual measures—enough that a slew of top Chinese developers say they fear a bubble. Here’s a look at the top markets:

There’s a reason demand in these cities is so rigid. Buyers from all over China buy homes in the biggest cities, assuming these to be the safest bets around. Therefore, these markets bear little resemblance to China’s smaller cities, where rumors of collapsing prices are rampant.

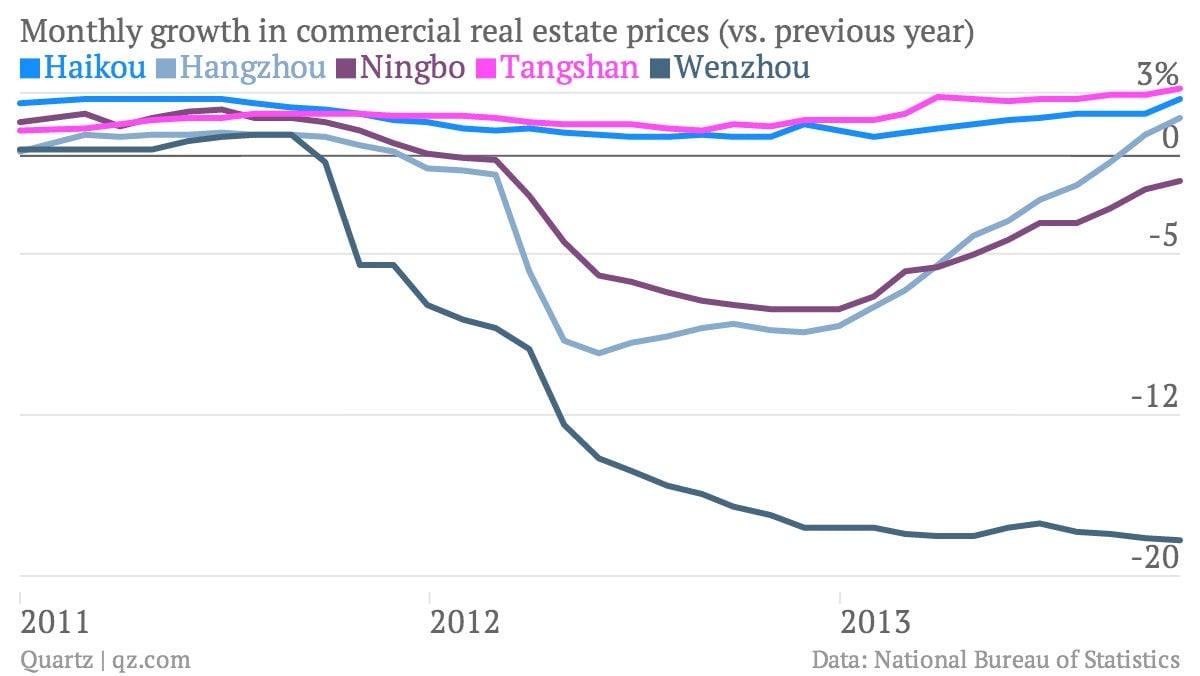

In fact, in many markets, housing prices have been falling for a while now. Even in some of China’s top 70 cities, demand is petering out. Home prices in Wenzhou, a city that suffered a mini-financial crisis two years ago, and Ningbo, an entrepreneurial hub on China’s eastern seaboard, have been falling for a while. Tangshan, Hangzhou and Haikou are also threatening to tip into the negative growth.

If more markets start to look like these, things could get dicey. Residential property is the lynchpin of the Chinese economy. Not only would collapsing prices drag down the huge part of China’s GDP growth driven by housing construction. Since an enormous share of personal and corporate wealth is tied up in the market, a steep drop in prices would also spark financial problems and possibly cause a bank panic.

The government knows what it should be doing to avoid this: instituting a property tax and reforming land rights so that local government are no longer driven to develop real estate in order to make money. China’s new leaders indicated on Nov. 15 that these changes are in the works.

But as we’ve argued in the past, China already has too many houses. And as The Economist reports, while the supply of new homes is surging, the government plans to build 200 new towns—undoubtedly full of shiny new apartment buildings.

In other words, the government plans to tamp down on demand while creating even more supply. Even if China doesn’t already have a housing bubble, these plans mean that it’s only a matter of time before it does.