Indian onion prices are going bonkers—again

This is an asset bubble that is bound to end in tears.

This is an asset bubble that is bound to end in tears.

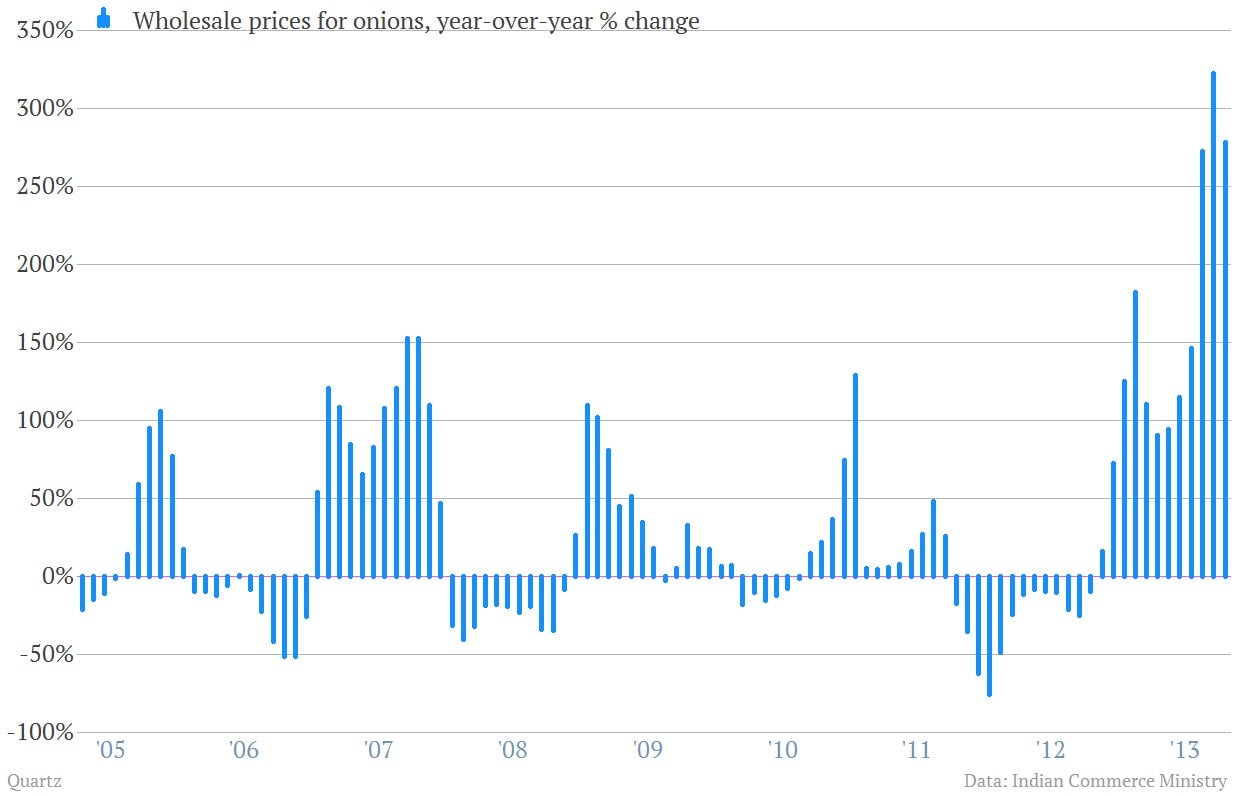

Prices for the humble onion, a staple for India’s one-billion plus people, continue to surge higher. Year-over-year prices have jumped 278% in October. That’s less than the 322% year-over-year surge seen in September. But it’s cold comfort to the hundreds of millions of Indians scraping by.

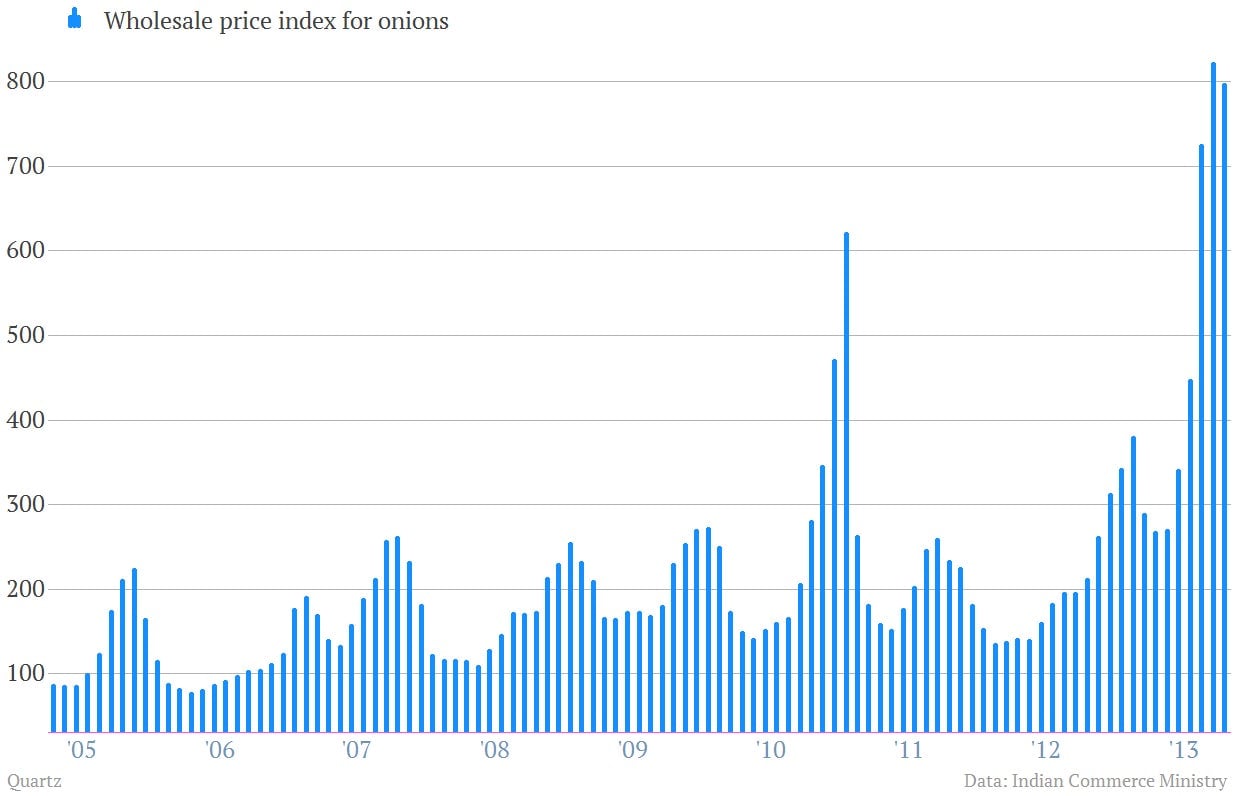

And that’s just the year-over-year change. The levels themselves are exceedingly high; the Indian commerce ministry’s wholesale price index for onions at around 795, just shy of the record high 820.5 seen in September.

Analysts say an increased supply of vegetables is partly the reason for the slight decline in prices. But the broader issue at play is the persistent weakness of the rupee, which adds an inflationary element to India’s notoriously shaky supply chain. (The rupee went through a sometimes scary rout in late summer.) The newly-installed Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram Rajan has made an effort to shore up the rupee by recently raising short-term interest rates, which in theory should help put downward pressure on inflation.

But there are other factors at play. And Rajan—like other emerging market policy makers—is also dealing with the prospect better-than-expected US economic data might ready the Federal Reserve to start easing up on its support for the economy. As a result, the Indian currency recently went through another feeble spell of 63 rupees to the dollar.

What’s more, there are politics to consider. In 1980, the Congress party rode to power with onion prices as the key issue of the campaign. In 1998, the rival Bharatiya Janata party lost control of the capital, New Delhi, as a shortage of onions pushed prices up sharply. In India, the political winds often reek of onion.