The German and Italian economies are moving in opposite directions

To paraphrase disgraced US past presidential contender John Edwards, there are clearly two Europes. Or rather, there’s Europe and there’s Germany, the largest economy on the continent.

To paraphrase disgraced US past presidential contender John Edwards, there are clearly two Europes. Or rather, there’s Europe and there’s Germany, the largest economy on the continent.

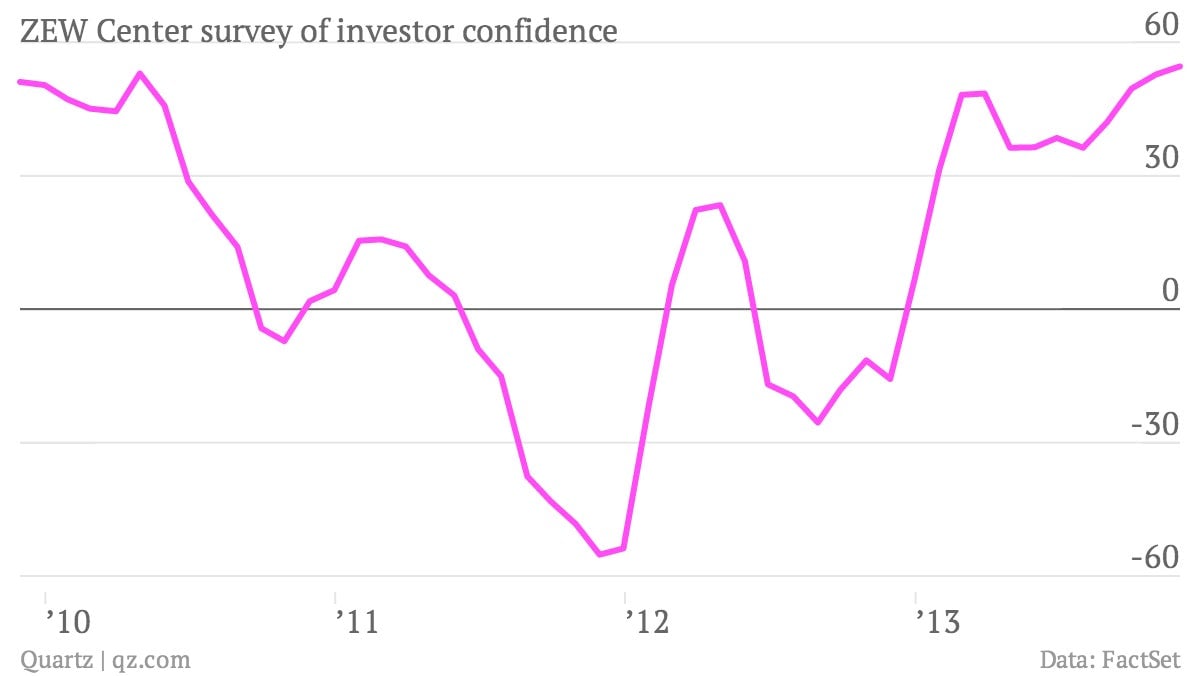

In Germany things are going pretty well. The economy is growing. Exports are booming. Home prices are rising, yet inflation—the national bogey man—is at a three-year low. And investors are practically ebullient. Check out today’s update on investor sentiment from the Zew Economic Institute in Mannheim, which rose 1.8 points in November to 54.6, its highest since October 2009.

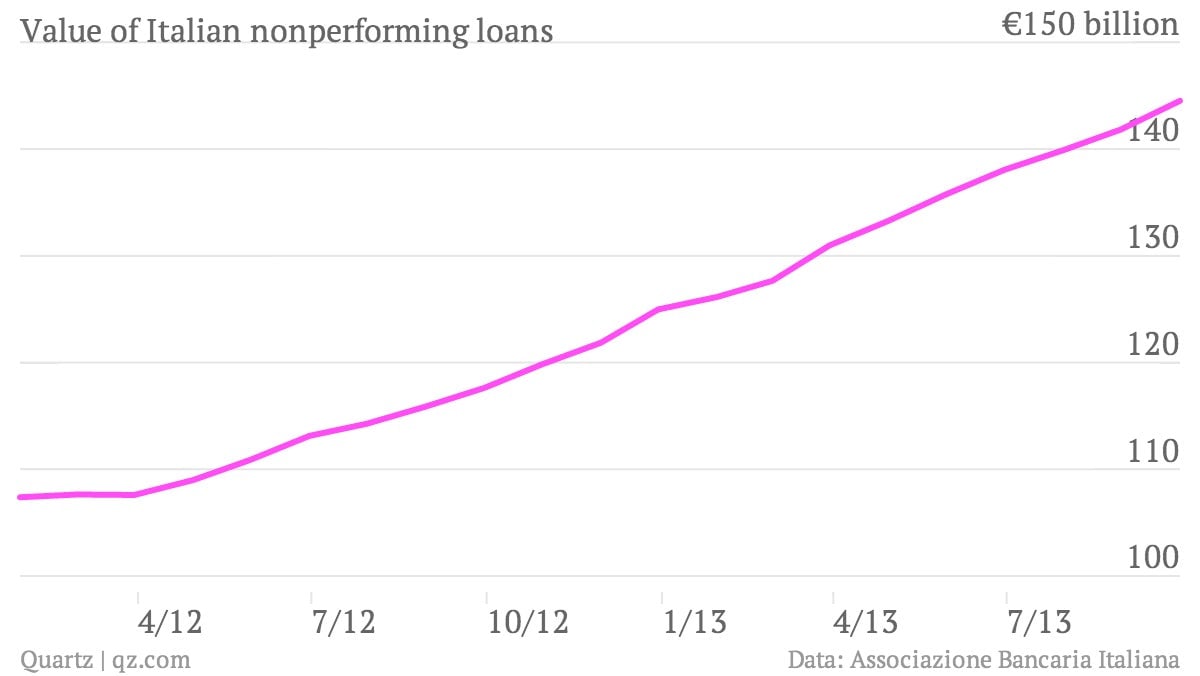

Meanwhile, a bit further to the south, Italy, the euro zone’s third largest economy, is flailing. It’s locked in its longest recession since World War II. Unemployment was at a record high of 12.5% in September. And because of these terrible economic conditions, the banking system is looking weaker and weaker. To wit, Italy’s main banking association was out with fresh data showing non-performing loans—problem loans that might eventually have to be written off as losses—continuing to climb higher. In fact, non-performing loans climbed 23% over the prior year’s level, to €144.5 billion ($195 billion) in September. As a proportion of lending, that’s roughly 7.5% the highest since 1998. Here’s a look.

This is the opposite of a virtuous economic circle. The weak economy weighs on the banking system, which cuts back on lending in order to husband its capital, which starves the economy of investment, which further weakens the economy and further weakens the banking system. This is how you get a decades-long deflationary spiral such as the one Japan is still struggling to shake off.

What’s the answer? Well, the nearest thing we have is aggressive central bank policy, a la Ben Bernanke. That means creating new money and shoving it into the economy, perhaps by buying financial assets like government bonds. Can the ECB do this? Sure. In fact, the rich-nation think tank that is the OECD today told the Frankfurt-based ECB to give it a shot. But the ECB is pretty much controlled by Germany, where money printing is decidedly a no-no. And that’s why the data disconnect between European nations is such a problem.

As long as everything seems to be fine for Germany, the exporting giant has little reason to allow for a course correction, which relegates Europe to just muddling along.