A map of the 90 corporations responsible for 63% of global carbon emissions since 1854

As the UN Climate Change Conference winds down today in Warsaw, an acrimonious dispute stands in the way of an accord on reducing global carbon emissions. Developing nations insist that industrial countries, which grew rich by spewing most of the extra carbon that has accumulated in the atmosphere, bear the burden of compensating those most at risk from rising sea levels and catastrophic weather. The wealthy countries counter that their citizens should not have to pay for the actions of their ancestors.

As the UN Climate Change Conference winds down today in Warsaw, an acrimonious dispute stands in the way of an accord on reducing global carbon emissions. Developing nations insist that industrial countries, which grew rich by spewing most of the extra carbon that has accumulated in the atmosphere, bear the burden of compensating those most at risk from rising sea levels and catastrophic weather. The wealthy countries counter that their citizens should not have to pay for the actions of their ancestors.

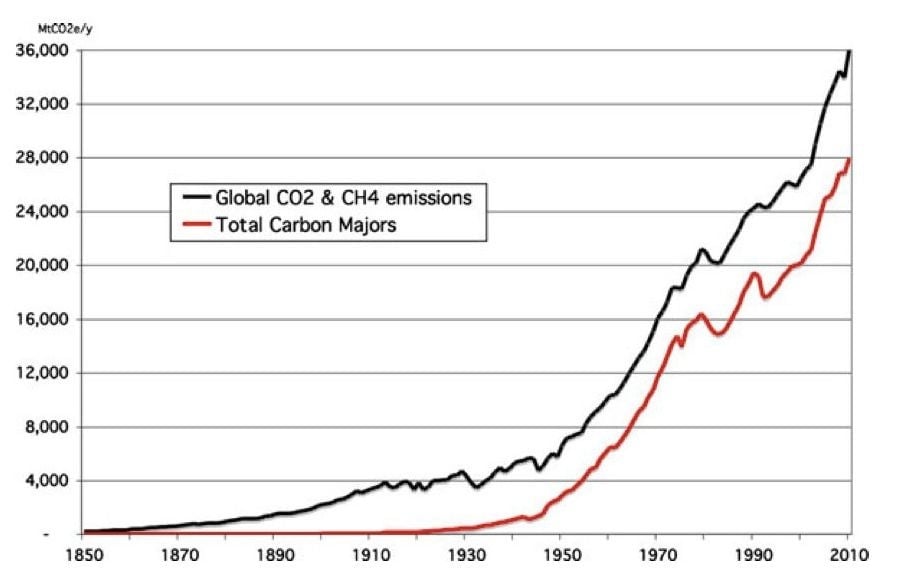

A new study, however, takes a different tack. It calculates the carbon emissions of corporations, not countries. Digging into historical and contemporary fossil-fuel production records, Richard Heede, a researcher with the Climate Accountability Institute, a US-based left-leaning non-profit, estimates that just 90 companies have been responsible for 63% of cumulative global greenhouse gas emissions between 1854 and 2010. Fifty of what Heede calls the “carbon majors” are investor-owned companies, and 40 are state-owned or state-affiliated producers of oil, natural gas, coal and cement (a significant source of carbon emissions).

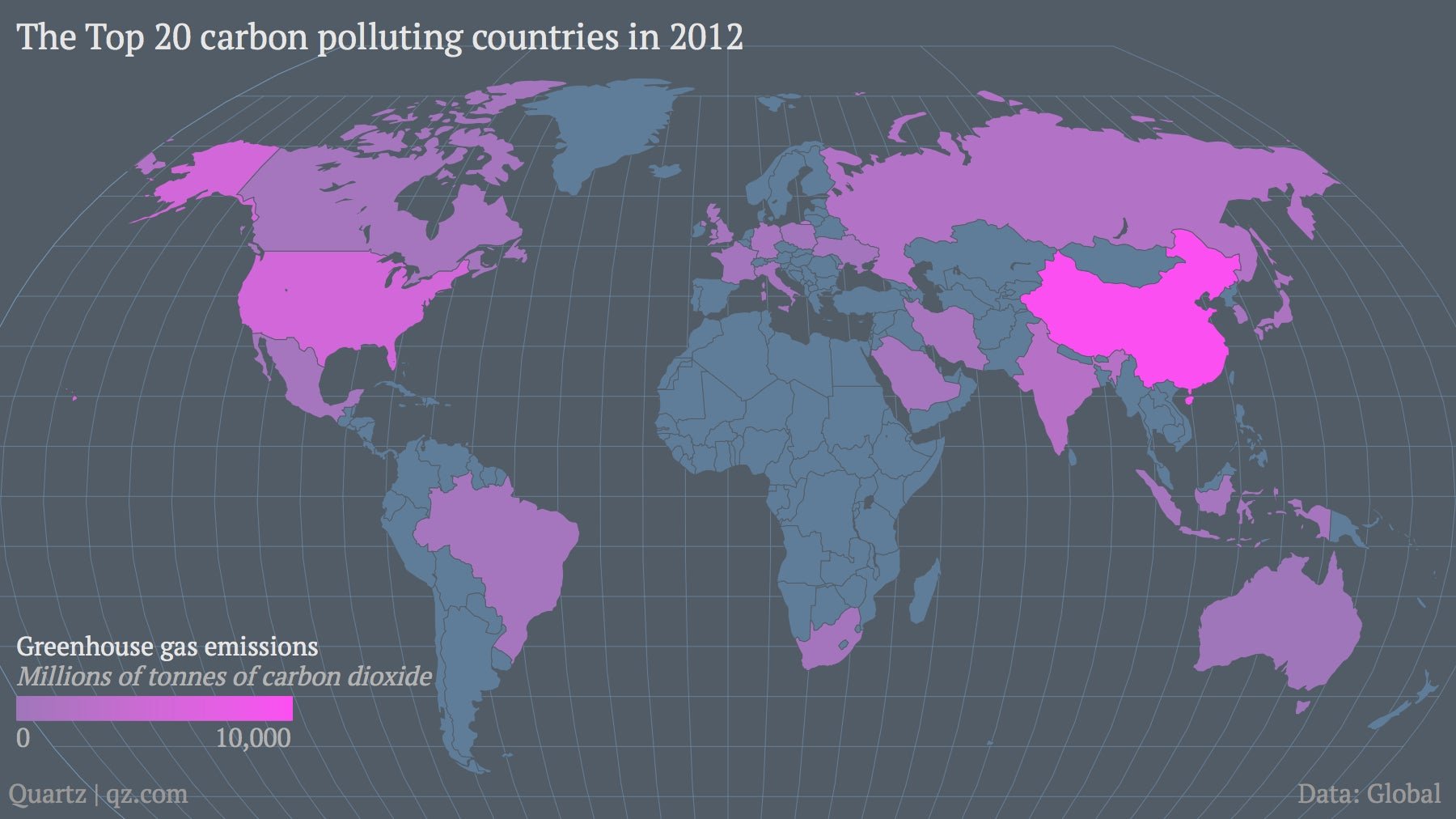

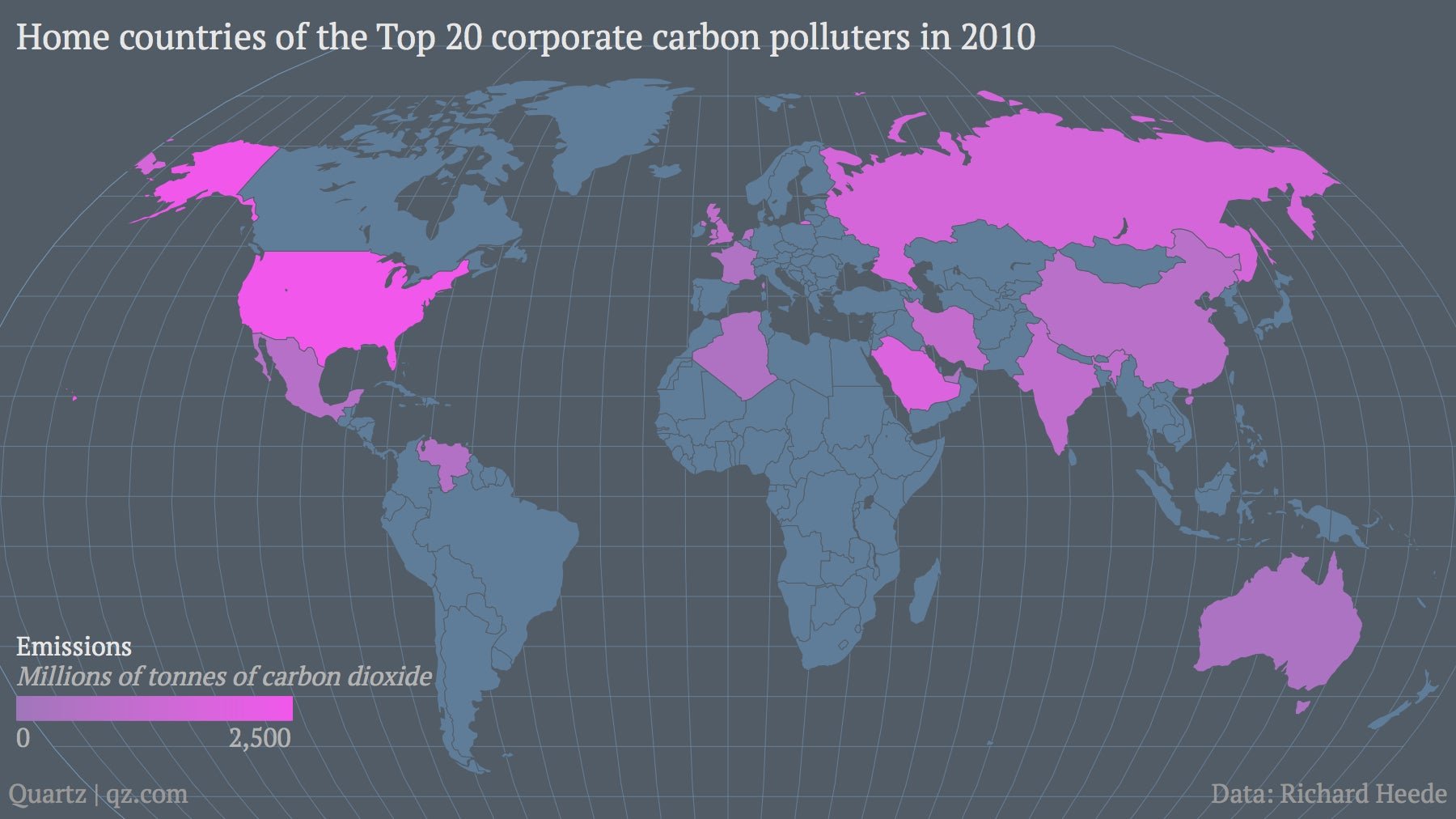

Looking at emissions in terms of companies rather than countries makes for a subtly different map of the world’s carbon problem. Here’s are the top 20 carbon-emitting countries in 2012, based on data from the Global Carbon Project, a non-profit research organization:

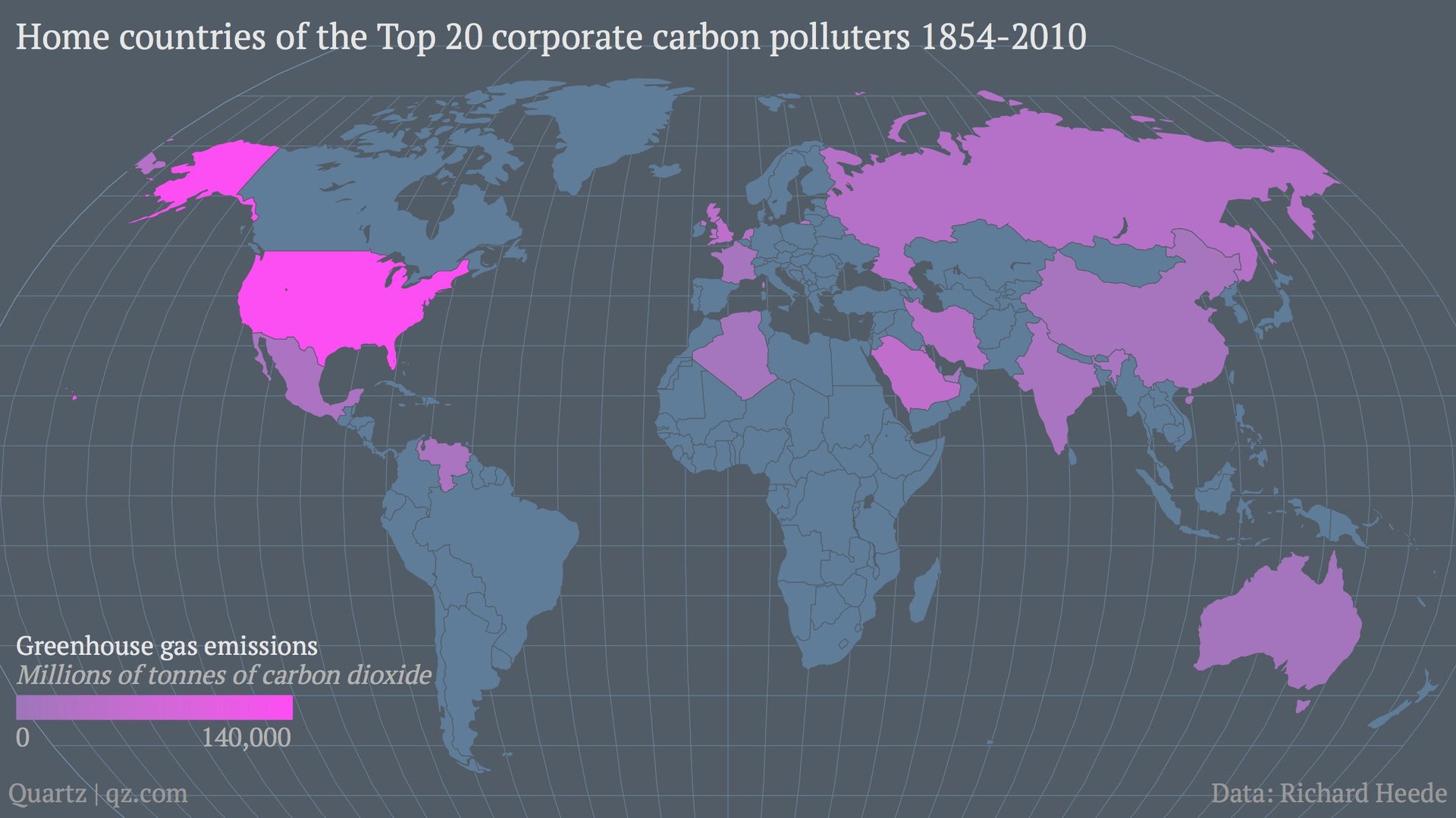

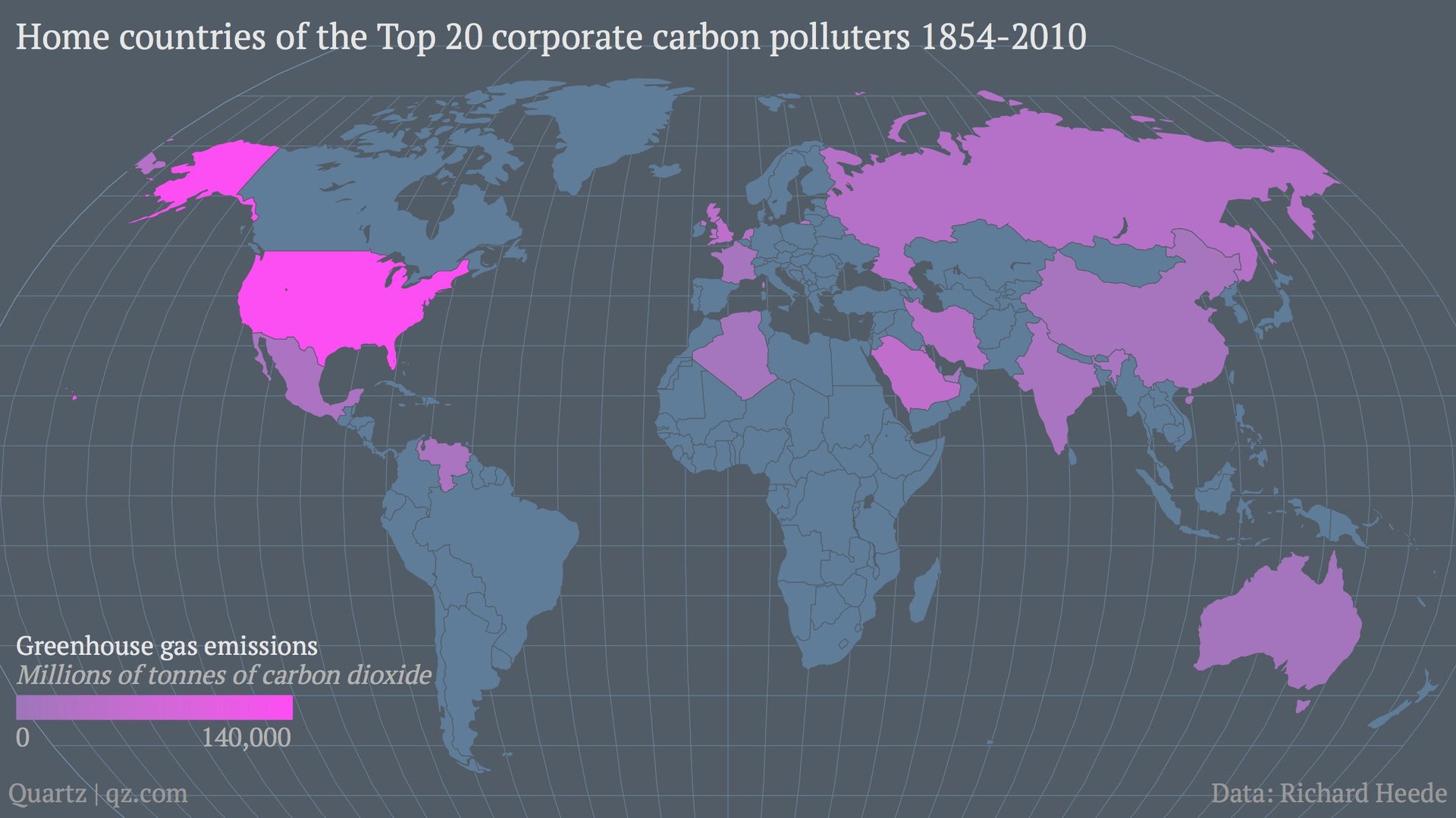

And here’s are the countries that are home to the top 20 carbon-emitting companies. Through this lens, the US continues to be a leading polluter—no surprise, given that it’s home to firms like ExxonMobil, which alone is responsible for 3.2% of historical carbon emissions by Heede’s calculation. But Europe and China in this framing play a smaller role, while the Middle East and Russia emerge as the home bases for some of the most polluting corporations—though Chinese and Indian firms are catching up.

Given how much money big energy companies have made from fossil fuels, Heede’s paper suggests, “some degree of responsibility for both cause and remedy for climate change rests with those entities that have extracted, refined, and marketed the preponderance of the historic carbon fuels.”

Heede isn’t saying that countries hit by the effects of global warming should necessarily seek compensation from those corporations. But he does propose that the data be used to regulate their future activities. “Energy companies have strong financial incentives to produce and market their booked reserves and oppose efforts to leave their valuable assets in the ground, but social and legal pressures may shift these incentives,” he writes. “Identifying who the major carbon producers are, and have been historically, may provide a useful basis for future social and legal pressure.”