When Typhoon Haiyan made landfall in Tacloban, in the Philippines, earlier this month, it whipped up 20-foot tsunami-like tidal surges so powerful that they killed most of the 3,900 people who died in the storm. The people of Tacloban “said ‘we were ready for the wind. We were not ready for the water,'” as presidential aide Rene Alemendras explained. “We tried our very best to warn everybody. But it was really just overwhelming, especially the storm surge.”

This might give you a better idea of why (the surge starts at 0:38):

Some of Haiyan’s destruction could have been prevented. But not with seawalls or dykes—with mangrove trees. Areas near Tacloban where mangrove forests hadn’t been illegally cut fared better, as a Philippines development consultant told Bloomberg. That’s because mangroves provide a natural buffer that slows down inland tidal surges, absorbing 70-90% of a normal wave’s impact. Here’s an animated version of how mangrove forests dampen a tsunami’s force:

The Philippines environment secretary, Ramon Paje, is now spearheading an effort to restore mangrove forests to 380 km (94,000 acres) of unprotected beach, focusing on Tacloban and other areas hard hit by Typhoon Haiyan.

Similar efforts are underway elsewhere in Asia, and have already spared damage to communities in Vietnam. Companies like Danone and Credit Agricole have invested around $4 million in mangrove reforestation on Sumatra, where a 2004 tsunami killed 170,000 people, reports Bloomberg. In exchange, they receive tradable carbon offset credits, since the curlicued aboveground roots of mangroves absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide.

There’s a lot of work to do. In the Philippines alone, coastal development and other factors have pared away four-fifths of the 500,000 hectares (1.2 million acres) of mangrove forest that once lined the archipelago’s coasts.

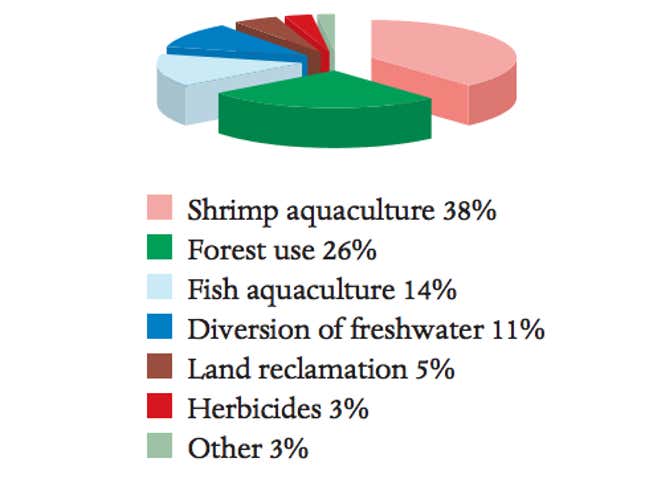

One of the biggest threats to mangrove forests is shrimp aquaculture. In Thailand, where an estimated 8,000 people died in the 2004 tsunami, shrimp farming has led to the destruction of 65,000 hectares of mangroves (pdf, p.9), reports the Environmental Justice Foundation, a non-governmental organization.