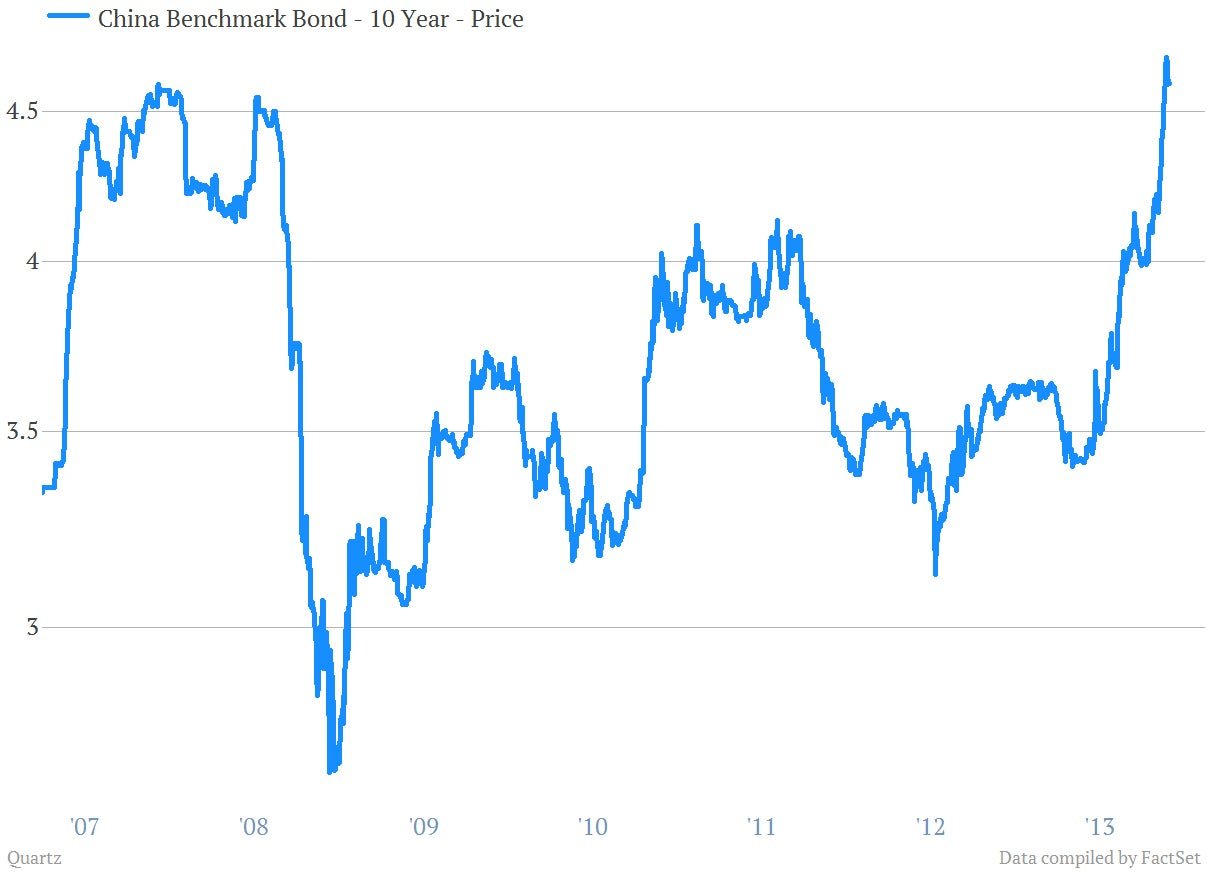

China’s bond yields are at their highest levels in nearly eight years

Credit is tightening in China again. But it isn’t showing up in the Shibor—the interbank lending rate that leapt precipitously last June—so much as China’s bond market. Government debt yields have surged to levels not seen in almost a decade, reports the Wall Street Journal (paywall), with the benchmark 10-year hitting 4.72% a week ago, settling at 4.62% on Tuesday, the last day for which there was data.

Credit is tightening in China again. But it isn’t showing up in the Shibor—the interbank lending rate that leapt precipitously last June—so much as China’s bond market. Government debt yields have surged to levels not seen in almost a decade, reports the Wall Street Journal (paywall), with the benchmark 10-year hitting 4.72% a week ago, settling at 4.62% on Tuesday, the last day for which there was data.

Corporate rates are rising even more sharply, causing issuers to balk at selling debt (paywall). ”If borrowing costs don’t fall in time, whether the real economy could bear the burden is a big question,” Wendy Chen, an economist at Nomura Securities, told the WSJ.

That sounds pretty dire. But is it?

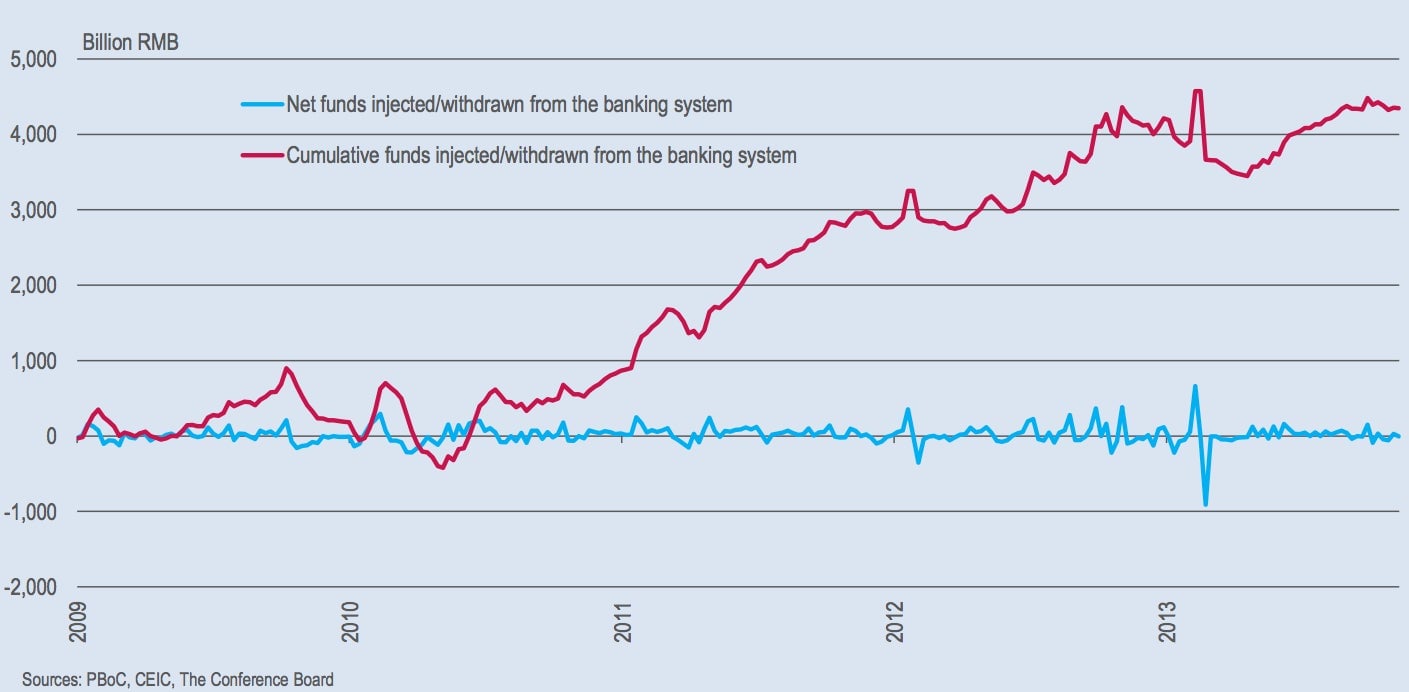

To answer that, let’s take a look at why this is happening. While the WSJ cites government “tightening” (meaning the central bank sucking funds from the interbank market to tame lending), the PBOC injected more money into the Chinese banking system last week than it’s done since late September. This chart from the Conference Board, a non-profit economic research group, isn’t exactly the picture of tight money:

So if it’s not tightening, what is it?

The source of surging bond yields comes from China’s labyrinthine interbank market, where banks have rigged intricate trades to keep loans off their books while recording deposits that aren’t actually there.

There are signs the party is over. While the central bank has recently called for “deleveraging,” the banking regulator has signaled an imminent interbank crackdown.

That’s prompted bigger banks to start getting out of off-balance-sheet trades, says Andrew Polk, economist at the Conference Board, leaving mid-sized banks short of cash (they’re far more reliant on interbank market funds). Meanwhile, banks are continuing to roll over loans to local governments, real estate developers and state companies, while generating too little from other loans due to the slowing economy. This is exacerbating the higher interbank rates, which never fully recovered to their pre-June levels.

And since the main buyers of both corporate and government bonds in China are banks, they have less extra cash with which to purchase or create assets.

There’s good news in all of this. China’s growth model makes money artificially cheap, encouraging wanton spending on projects that generate little cash and build up local government and corporate debt. Bond yields reflecting something closer to the real cost of borrowing discourage them from piling on more debt.

In theory, at least. Even as the government makes feeble efforts to slow growth in official lending, it can’t control the surging credit growth in the interbank market. To avoid a debt crisis, the government needs to crack down on illicit interbank lending and wean that market off central bank liquidity. Easier said than done, says Polk.

“Every time it attempts to do so the system becomes too strained. At this point a so-called beautiful deleveraging may be impossible, so it’s a matter of when the regulators become willing to accept the necessary pain,” he says. “The longer they push it off, the more unbearable the potential pain will be.”