For a technology with world-bending potential, most Crispr innovations and businesses can be traced back to surprisingly few scientists and their labs. Like evolution itself, the field is constantly branching in new directions, but the same names and terms keep popping up. Understand them, and you’ll have at least a passing chance of faking your way through a cocktail party discussion.

The technologies

Crispr: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats. A type of molecule, found in many bacteria, that can be programmed to search for a particular sequence of DNA. Usually attached to a protein called Cas9 that acts like molecular scissors, snipping the DNA of invading viruses. Scientists have repurposed Crispr as a genetic search-and-replace tool, making gene editing of living things simple, fast, and efficient for the first time.

Gene Editing: Using Crispr or other molecular tools to reprogram the genes of living things by rewriting their DNA code. Unlike traditional genetically modified organisms (GMOs), gene editing does not import whole genes from other organisms, potentially making it more palatable to regulators and the public.

Gene Drive: A Crispr system built into an organism’s sperm or eggs that guarantees inheritance of a particular gene by all offspring. When offspring inherit a Crispr gene drive from one parent, it cuts the opposite gene (inherited from the other parent) and copies itself in place, so that individual has two copies of the gene drive and is guaranteed to pass one down to all offspring, where the same thing happens. In theory, it can eventually drive a gene into all members of a species, and could be used to wipe out weeds or agricultural pests. A gene drive that kills the females of one type of malaria-carrying mosquito, and is passed on by males of that species, is being perfected in London.

DNA Synthesis: The manufacturing of DNA and genes from simple chemicals, using a kind of inkjet printer that shoots out the As, Cs, Gs, and Ts of the genetic code. The DNA produced is identical to the DNA found in the cells of living things. The cost of DNA synthesis has fallen so fast that most genes can now be printed for a few dollars.

Sherlock and Detectr: Competing diagnostic technologies invented by Feng Zhang and Jennifer Doudna, respectively, that can use Crispr to enable health care workers to take a genetic sample from a person, and identify any pathogen in the sample, using a simple device that acts like a pregnancy test. Could revolutionize medical field work in the developing world.

CAR-T: An abbreviation for “Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cells.” Many cancers are able to spread because they evolve a mutation that makes them invisible to the immune system. In CAR-T, some of a patient’s immune cells are removed from the body, engineered to target the cancer cells, and returned. CAR-T (which predates Crispr) has had some breakthrough successes, but it is very slow and very expensive. A new generation of faster, cheaper, off-the-shelf Crispr CAR-T therapies is on the way.

Gene Therapy: Treating people with genetic diseases by using Crispr or other genetic tools to alter the functioning of their genes. Widely expected to become a cornerstone of medicine.

Cas9: The enzyme (a type of Crispr-associated protein) that is generally attached to Crispr and does the DNA cutting once Crispr finds the spot to cut. Cas9 was the first Crispr-associated protein discovered and patented, but we have since discovered many more that can perform other functions. Thanks to this variety of Crispr-associated proteins, Crispr is looking more like a genetic Swiss Army knife than the genetic scissors we once thought it was.

The players

Jennifer Doudna: The UC Berkeley biochemist who co-discovered the Crispr-Cas9 system for gene-editing. She also cofounded Mammoth Biosciences, which is developing Crispr diagnostic devices that can be used with cell phones, and Caribou Biosciences, a company with exclusive rights to UC Berkeley’s Crispr technology. Caribou then licensed the technology to Intellia Therapeutics (for which Doudna is also a founding member).

Feng Zhang: A core member of the Broad Institute, professor of neuroscience at MIT, and inventor of many of the best Crispr tools. Zhang has his name on more than 350 patents involving Crispr, including arguably the most important one: Using Crispr-Cas9 to edit plants, animals, and people.

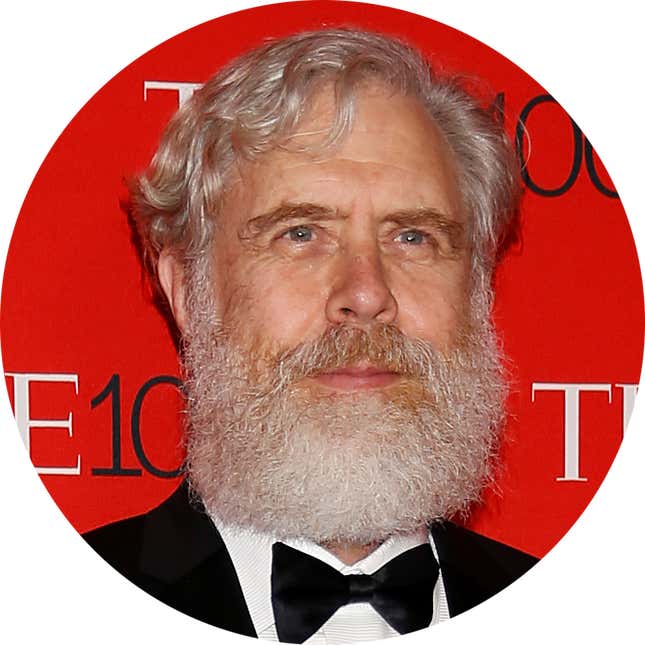

George Church: The world’s most famous synthetic biologist (and the only one to do Colbert—twice!), who has a long white beard that makes it look like he just stepped off the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel after giving life to Adam. He has launched so many ventures that he described the list, as he introduced it at one conference, as “my conflict of interest slide. I am highly conflicted.”

He’s behind the Human Genome Project (which hopes to synthesize a complete human genome from basic chemicals) and the effort to bring back the woolly mammoth. He’s also the co-founder of 22 companies, including Rejuvenate Bio (Crispr injections to extend the life of your dog), Editas Medicine (see below), and Egenesis (which is developing Crispr-edited pigs whose organs can be used for transplants).

Kevin Esvelt: The MIT scientist who first realized how Crispr could be used to build a “gene drive” that potentially forces a gene into an entire species, changing it or even driving it to extinction. Esvelt has since called for a ban on any commercial use of gene drives, and for a change in the rules of science to prevent experiments from happening in secret.

He Jiankui: The Chinese scientist who secretly created the first “designer babies” in 2018 by using Crispr to make twin girls immune to AIDS. He announced the existence of the babies in November 2018, was widely denounced, and has been under house arrest ever since

The companies

Broad Institute: An elite research institution that funds interdisciplinary teams from Harvard and MIT to explore genetic solutions to disease. It straddles industry and academia to bring high-challenge, high-reward projects to market, and holds hundreds of Crispr patents.

Editas Medicine:

A Cambridge-based company founded by George Church, Feng Zhang, and Jennifer Doudna (who later departed) to commercialize Crispr therapies. It’s currently involved in clinical trials for Crispr-based gene therapies and cancer treatments and holds the exclusive Broad Institute license for using Crispr-Cas9 in human therapeutics.

Crispr Therapeutics: A Swiss company using Crispr-Cas9 to treat genetic disease. It has clinical trials in the works for sickle-cell anemia and beta thalassemia, as well as CAR-T cancer treatment. Could be first to market with a Crispr cancer therapy.

Intellia Therapeutics: A startup spun off from Caribou Biosciences that is developing Crispr therapies for liver diseases and leukemia. Its earliest clinical trials aren’t expected until 2020.