More trade is now settled in yuan than in euros. But global dominance is still a ways off

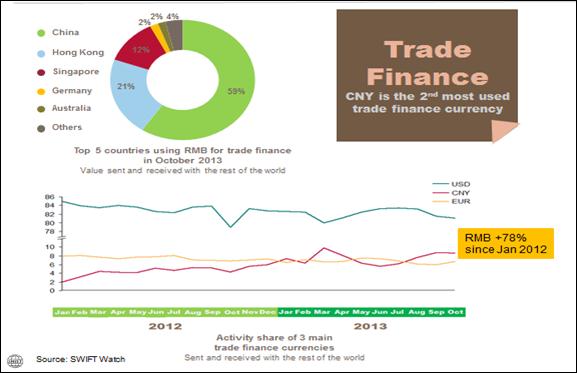

Though China trades more goods than any other nation, the yuan’s global presence is tiny. That’s changing, though. In October, the yuan accounted for 8.7% of global trade finance, surpassing the euro (6.6%) to become the world’s second-most-used trading currency behind the dollar, according to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT).

Though China trades more goods than any other nation, the yuan’s global presence is tiny. That’s changing, though. In October, the yuan accounted for 8.7% of global trade finance, surpassing the euro (6.6%) to become the world’s second-most-used trading currency behind the dollar, according to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT).

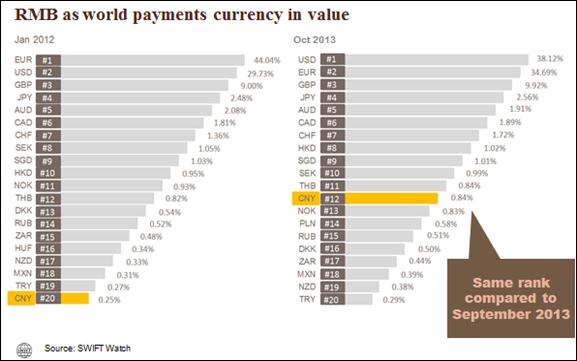

It was a quick role reversal: In January 2012, the euro claimed 7.9% of global trade, compared with the yuan’s 1.9%.

The trend is important because the yuan’s rise reflects the world’s confidence in China’s financial system, economy, and government. Many see this prospect as a threat to dollar (and, to some extent, euro) supremacy, which helps those countries to borrow cheaply. But while it’s certainly true that global businesses are increasingly willing to accept yuan, this particular milestone doesn’t really tell us much about those prospects.

First, the SWIFT report tracks settlement, not invoicing. As economist Yu Yongding has argued, Chinese importers tend to settle transactions in yuan (pdf, p.5), which they can invest in the mainland, but the prices are often set in other currencies. This lets them profit from yuan appreciation and high mainland interest rates relative to Hong Kong, where they would otherwise store deposits. Since SWIFT doesn’t break out exports and imports, it’s hard to know whether this is happening. But as you can see in the chart below, yuan settlement dropped sharply in June, when the Chinese government cracked down on fake trade invoicing.

It picked up again in September and October, when investment inflows surged. That means it’s possible that the yuan’s newfound popularity reflects speculation more than it does confidence in China’s currency and its economy.

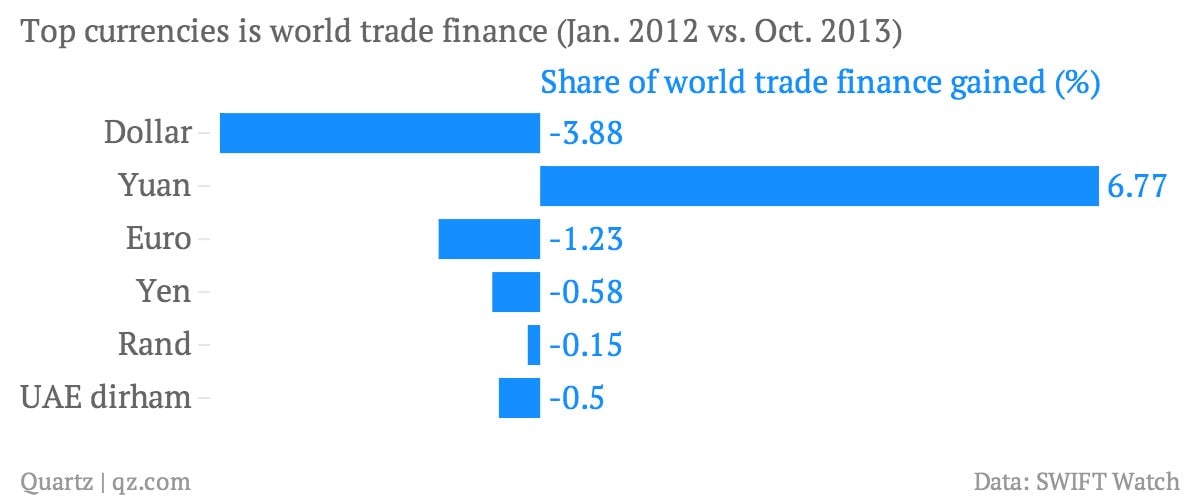

But regardless of why businesses are using the yuan, the fact is that this trade is supplanting the dollar (as well as other major currencies):

Here’s who’s losing out:

Now for a bit of context. The US dollar’s share of world trade finance fell from 85% in January 2012 to 81% in October 2013, meaning the dent the yuan made is tiny. That said, 8.7% is approaching the roughly 10% share of global trade that China claims. It will be interesting to see if yuan trade finances surpasses that percentage in the next few years:

That gets us to a final point: whether the yuan will soon be used for things besides settling Chinese trade deals, requiring the government to let the currency trade more freely. Some are sanguine. “International use of the yuan is increasing as China opens up its capital markets,” reports Bloomberg.

But there’s a big difference between settling trade in yuan and using it for investment or as a reserve currency. The government has done little to open China’s capital account (more here). Small wonder. Doing so would risk a deluge of illicit outflows, driving up interest rates and probably crashing China’s already demand-sapped stock market. Letting the market set interest rates would likely bankrupt hundreds of state-owned companies. And to guarantee sufficient yuan liquidity, China would probably need to run a trade deficit, stunting growth.