As the security of the greenback falters, a slew of recent headlines suggest that the yuan continues its global conquest. On Oct, 15, British chancellor George Osborne said that new agreements with China will seal London as a “the pre-eminent center” outside of Hong Kong for “internationalization of the renminbi,” reports the Financial Times (paywall), using the alternative name for the yuan. That comes on the heels of the European Central Bank’s €45 billion ($57 billion) currency swap with the People’s Bank of China (PBOC).

Do these developments mean the yuan is emerging as “a great global currency,” as Osborne put it? Not really. Breaking down each of the agreements, here’s why:

The sterling will join the dollar, yen and Australian dollar as currencies that companies can trade directly for yuan (outside of China)

Letting British and Chinese businesses settle trade directly, rather than through the US dollar, in theory reduces exchange-rate risk and transaction costs. Businesses usually use the same currency to invoice an order (set the price) and settle (pay for it). Chinese importers have been invoicing in dollars, but settling in yuan, economist Yu Yongding argues (pdf, p.5). Why? To profit from the yuan’s strengthening. That means the demand for the yuan in global trade results from the government’s currency manipulation, not from confidence in the currency’s reliability. (Tellingly, Chinese exporters mostly still use dollars.)

China will let London-based institutional investors buy 80 billion yuan ($13.1 billion) of Chinese securities

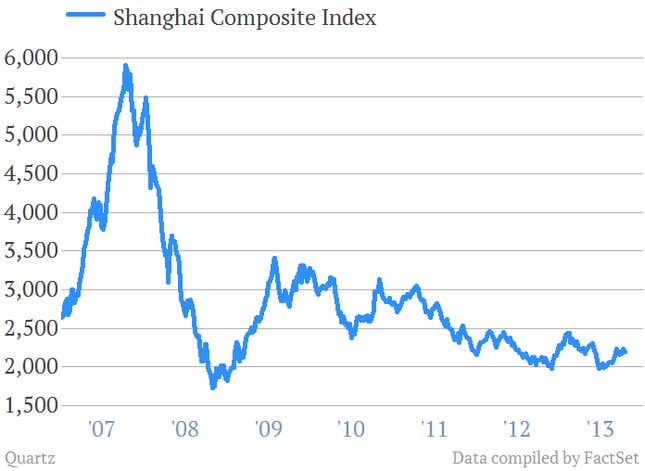

Get excited, UK-based institutional investors! The Shanghai composite is down 9% this year and down 64% from its 2007 peak. Alternatively, those investors can buy bonds from many already debt-swamped Chinese corporations or help fund that debt another way, by lending yuan to Chinese banks. Small wonder that foreigners approved for this scheme have only invested 43% of the quota the Chinese government allotted them.

Chinese bank branches will be able to open in London

This means Chinese banks will be able to make more commission income on yuan trading, if Hong Kong’s experience is any guide. And since Chinese banks will operate as branches—rather than subsidiaries—they will be subject to looser capital requirements, allowing them to “significantly scale up their activity in the UK,” said Osborne. This could help fund more projects like this £650 million ($1 billion) Manchester airport investment. That will help advance Chinese banks’ reputations and improve their profitability, perhaps, but it doesn’t do much for “internationalization.”

The ECB and the PBOC will swap 350 billion yuan ($57 billion)

Central banks sign bilateral currency swaps to give them access to an emergency stash of cash to use in case trade financing in dollars—in which more trade is settled—freezes up, the way it did after Lehman Brothers collapsed, explains Patrick Chovanec of Silvercrest Asset Management, an expert on China’s economy. “One of the reasons you need that kind of agreement is that those currencies aren’t widely traded,” Chovanec told Quartz (meaning that dollar supply seized up, it would be hard to find yuan to keep trade going).

“But [central banks are] not actually swapping currency,” he says. “They’re not holding [yuan] as reserve currency.” That means most EU-China trade, like that between China and the signatories of its 23 other currency swaps, is still settled in dollars.