Why an MIT professor says we should all learn like kindergartners if we want to succeed

In 1999, on the cusp of a new millennium, MIT professor Mitchel Resnick was on a panel where everyone was asked to pick the most important invention of the last millennium. One person said the printing press, another said the steam engine, and another the computer. Resnick said kindergarten.

In 1999, on the cusp of a new millennium, MIT professor Mitchel Resnick was on a panel where everyone was asked to pick the most important invention of the last millennium. One person said the printing press, another said the steam engine, and another the computer. Resnick said kindergarten.

Resnick recounted his reasons last week at BETT, a trade show in London for educational technology. From its arrival in the 1830s, he said, kindergarten eschewed the ”broadcast” method of teaching by which teachers disseminated information to students. That style would never fly with five-year-olds. Friedrich Froebel, the German educationalist who invented the “garden for children,” instead offered “a radically new approach to education, fundamentally different from schools that had come before,” said Resnick, a professor of learning research who also heads up the MIT Media Lab’s Lifelong Kindergarten research group.

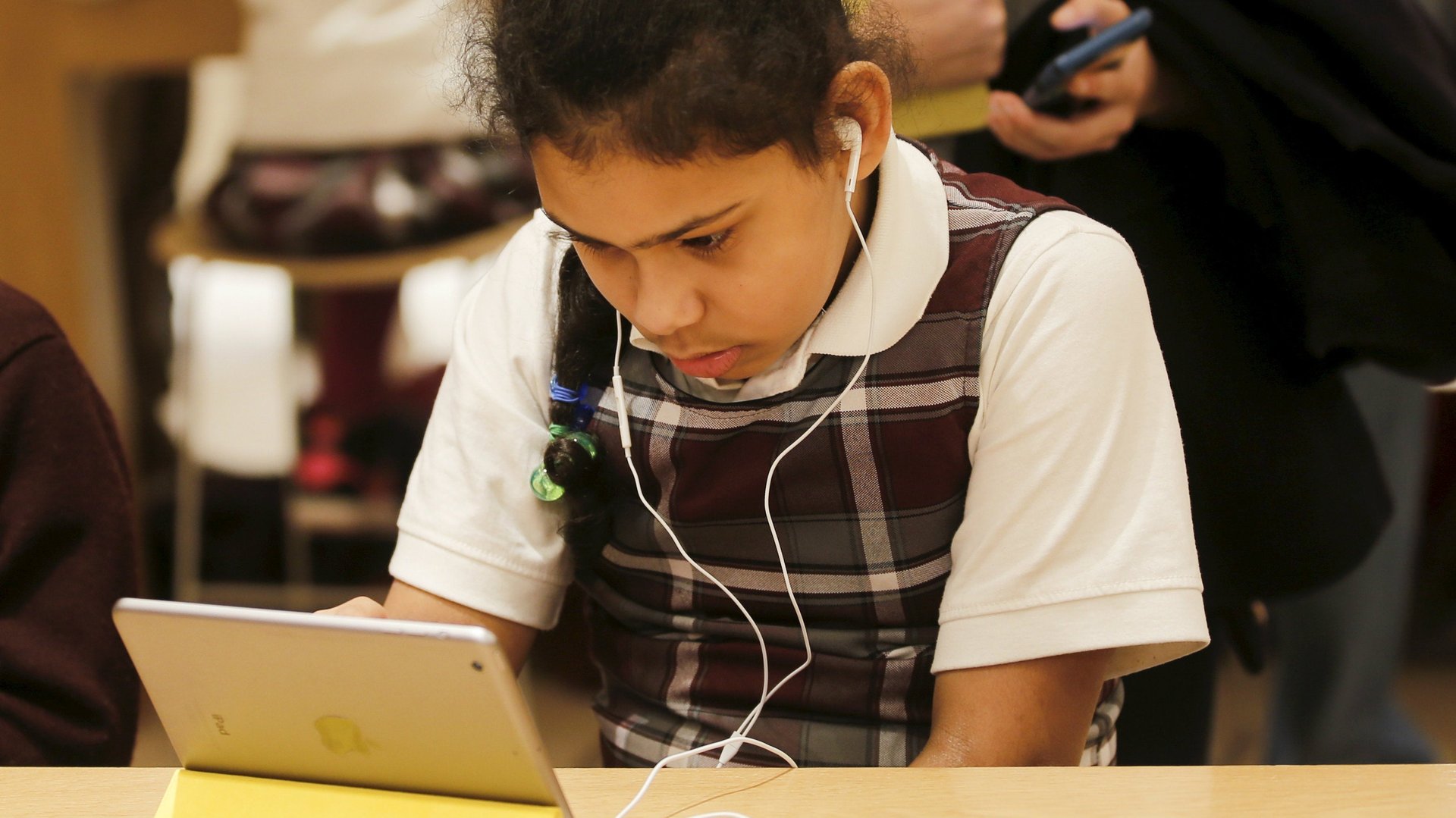

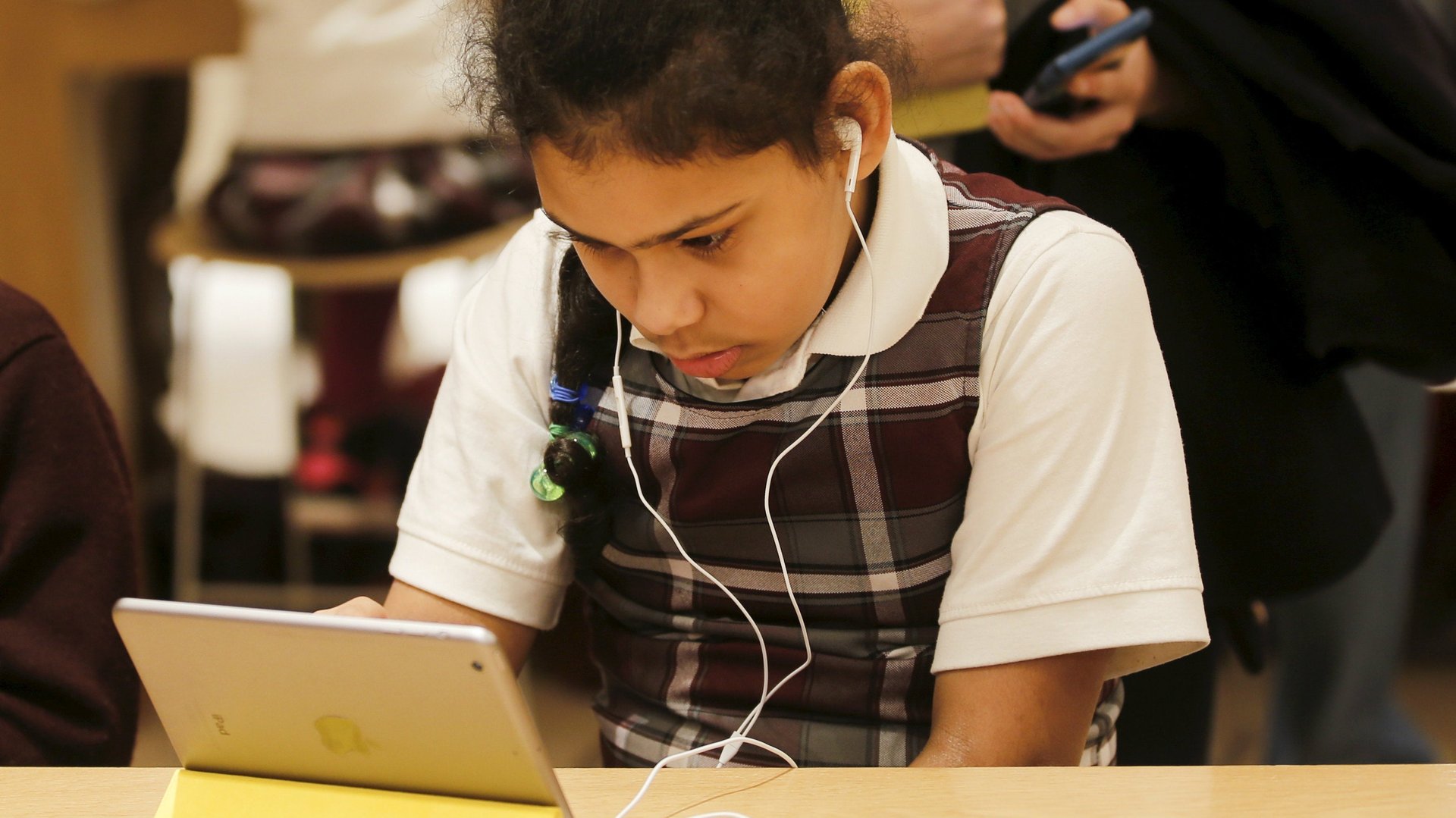

Kindergarten was designed to be playful and interactive, with kids learning through experimentation and exploration. According to Resnick, the approach remains “ideally suited to the needs” of today—and not just for five-year-olds. Learners of all ages could benefit from the kindergarten approach to the creative process, which typically involves joyfully creating things, destroying them, iterating, collaborating, and trying again. “We need to make the rest of school, the rest of life, more like kindergarten,” Resnick said, “to playfully create things with each other.”

The idea that education needs to be reshaped to better suit the demands of a rapidly changing economy is hardly new. But the promise of the kindergarten approach seems an especially fitting model for “lifelong learning,” the catchphrase which reflects the reality that a hyper-automated, gig economy will require workers to continue to learn and iterate on their own careers.

The lab group Resnick runs at MIT has developed four principles to apply the kindergarten spirit to all learning. Resnick calls them the 4 Ps: projects, passion, peers, and play. Kids should actively work on projects, which intersect with something they are passionate about, while working with peers in a playful environment, he says. (He also wrote a book about it.)

Resnik’s work goes way beyond theory and ideas. He spearheaded the MIT Media Lab project that invented Scratch, a programming language and online community which allows children to create and share interactive stories, games, and animations. As he explains in this TED talk, Scratch brings the four Ps online—where kids live—enabling them to create projects and collaborate based on what interests them. It now has 30 million registered users, and every day children share more than 30,000 projects, Resnick said. Scratch 3.0 has just been launched with extensions for translation, program motors, lights, and sensors.

The project underscores one the great educational shifts that the internet has enabled: making students creators and not just consumers of content. In Scratch’s case, it wasn’t deliberate. Back in 2007, when Scratch launched, Resnick and his team assumed teachers would create content for students. “We never imagined kids would make tutorials,” he said.

At BETT he shared the examples of “bubble103“, a South African girl who created and shared 32 projects including ones on the water cycle; the “fabulous farming game;” and one called “ya gotta love variables.” Another project called “Color Divide” brought together six people from four countries to write an animated story about a mythical world called Aurora. It’s been viewed 34,000 times and loved 3,000 times.

Kids learn more when they are engaged with the content in front of them. But Resnick highlights another, often overlooked point about children and the traits they have that adult learners would ideally replicate: kids don’t want things to be easy. They want them to be meaningful. And creating tools for them to have agency, and help shape their own learning, is one way to fulfill that.