Today (Jan. 31) is the deadline WalMart set for direct suppliers of leafy greens to join its blockchain-enabled food-tracking network. The corporate giant’s latest innovation—which arrived as a mandate—is an admirable step toward improving food traceability and safety, but might seem odd if you’re a blockchain purist.

Blockchains are digital record-keeping systems. They’re similar to databases, except everyone participating in the network can verify when a change has been made. (This is sort of like Google Docs, but it’s an imperfect analogy, because documents have owners who can delete them, and the service depends on one organization, Google.) Also, in a blockchain setup, each change must be processed according to a set of rules before records are updated across the entire network.

For Walmart, these properties are useful in a complex setting like tracking food provenance in a multi-party supply chain. In a simulated recall last year, the company used blockchain to reduce the time it took to trace the origin of a bag of mangoes from almost seven days to just 2.2 seconds.

Ultimately, for Walmart ,“blockchain” is a fancy way of saying: 1) this information is cryptographically secured and 2) any changes—from beginning to end—will be authenticated and recorded by all participants on the network.

But what Walmart calls a blockchain isn’t necessarily what the crypto community considers a blockchain, at least in its original conception.

There are hundreds of papers, presentations, TED talks, and YouTube videos dedicated to explaining blockchain—and many more dedicated to explaining bitcoin, which uses one specific version of blockchain (a proof-of-work system which relies on SHA-256).

Corporate blockchains like Walmart’s are sometimes derided within crypto circles because they’ve taken something from the open-source/cryptocurrency community and reformulated it in a private, albeit useful, manner. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that—improvements can, and should, come from anywhere. Nobody “owns” blockchain any more than they own the concept of wearing shoes.

The rub is that corporate blockchains are typically “permissioned,” meaning that they’re only accessible to a limited set of participants. So, even if private blockchains augment record keeping, save time, and perhaps billions of dollars, nothing about the business fundamentally changes.

Although slower to develop than private implementations, public blockchains are the foundation for cryptocurrencies and potentially, for applications that could challenge entrenched digital service providers. For example, Filecoin is an open-source cryptocurrency payments system which aims to offer digital storage. (Think DropBox, but completely peer-to-peer and with a cryptocurrency mixed in.)

But here’s the catch: Filecoin, which raised more than $250 million through an initial coin offering, hasn’t shipped yet. And indeed, public networks face enormous challenges in scaling, user experience, and even basic economics. So, regardless of their war chests, it’s hard to say whether these crypto-titans will succeed or run aground.

In the near term, private systems, like Walmart’s food tracking blockchain, are the most promising, and in the long run, public networks could be revolutionary (though certainly not in their current form). No matter your preference though, blockchain isn’t just a buzzword. What it means just depends on how it’s used.

Chart interlude

Blockchain is an increasingly popular topic of conversation on corporate earnings calls and presentations. It’s become a trope for buttoned-up execs to dismiss the unregulated, freewheeling world of cryptocurrencies but embrace the underlying technology that powers them. The data very clearly illustrate this trend, although for the most part blockchain chatter in many boardrooms hasn’t yet turned into meaningful action.

Crypto-meets-finance

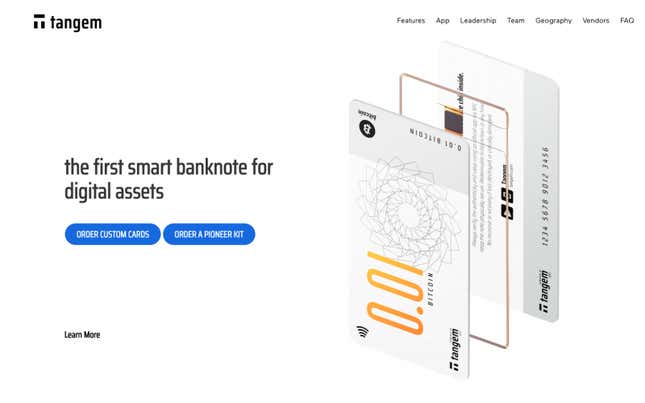

A Swiss firm will produce a physical version of the Marshallese cryptocurrency. Tangem, based in Zug, Switzerland, announced on Monday that it will issue plastic cards which can be used to store and spend the Sovereign (SOV), the national cryptocurrency of the Marshall Islands.

Although the Marshallese parliament approved the SOV as legal tender—alongside the US dollar—in February 2018, the International Monetary Fund has warned that the national crypto “would increase macroeconomic and financial integrity risks,” and put the country in danger of losing its last relationship with a correspondent bank dealing with US dollars. In November, Marshallese president Hilda Heine narrowly survived a no-confidence vote related, in part, to her support of the controversial SOV.

Tangem claims its cards enable “immediate transaction validation, zero fees and no internet connection requirements for end users” of the SOV. While this is true of a physical transaction—like handing a gift card to a friend—ensuring that cards actually hold value sounds trickier (and may require an Android phone, with an internet connection).

According to Tangem’s FAQ, to remove value from a Tangem Note, a user must hold their Android phone against the card “for one or two minutes.” The delay is to guard against unauthorized extractions. Also, the company warns, “If you give your Tangem Note to a stranger and leave it out of sight for more than two minutes, you should always validate it when they give it back to you — in case they extracted its value.” And what happens if notes malfunction? Well, the company says, at even a hint that something’s broken, you’ll be asked to extract the card’s value (presumably through the validation app), but makes “no further warranties.”

Setting aside the macroeconomic risk of the SOV—which has a capped supply of 24 million tokens—Tangem’s crypto notes seem to combine the best properties of cash (transferability and anonymity) with the worst aspects of gift cards (checking if they have any value). Verifying Tangem banknotes sounds more time-consuming than checking for a watermark on a regular banknotes, and while a cash-verification system is innovative, it doesn’t sound user friendly, especially if the notes lack a standardized value.

Quartz has requested Tangem’s independent lab test results, as the company purports an internal standard of less than one failure per billion cards. Members of Tangem’s executive team, led by CEO Andrew Pantyukhin, did not immediately return a request for comment.

Welcome to Private Key

Today’s edition of Private Key marks its first for Quartz members. While subscribers to the Private Key email are familiar with its coverage of the world of cryptocurrency and blockchain, now all Quartz members can benefit from its insights and analysis. You can look for us every Tuesday and Thursday. We’re glad to have you along for the ride.

For subscribers, nothing changes except the days you’ll receive your email. But as a reminder, you are also now Quartz members, at no additional cost, and have access to Quartz’s weekly Field Guides, our essential deep dives into the most urgent topics affecting the global economy; Tipping Points, a new column on finance and economics; and new a weekly take on how to spend your money intelligently. We’ll be be rolling out additional offerings over the course of 2019. We hope you take a look around.

Private Key subscribers have been sent an email with instructions on how to activate their account, but if you have problems or questions, feel free to email us at members@qz.com.

Today’s Private Key was written by Matthew De Silva and Jason Karaian and edited by Oliver Staley. If it’s the ultimate game, how come they’re playing it again next year?