Research shows your brain physically ages faster when you’re depressed

New research out of Yale University shows depression can physically change a person’s brain, hastening an aging effect that might leave them more susceptible to illnesses associated with old age.

New research out of Yale University shows depression can physically change a person’s brain, hastening an aging effect that might leave them more susceptible to illnesses associated with old age.

Scientists have, in this past, found all sorts of evidence to show how depression impacts the brain and other parts of the body. The condition has been linked to a heightened risk for headaches, muscle pains, and sleep problems, among other things. And it can create a negative feedback loop: a 2004 study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychology found that “the worse the painful physical symptoms, the more severe the depression.”

With that in mind, Irina Esterlis, a researcher at the Yale School of Medicine, set out to learn more about how depression impacts the brain, specifically. She presented her findings Feb. 14 at the American Association for the Advancement of Science conference in Washington DC.

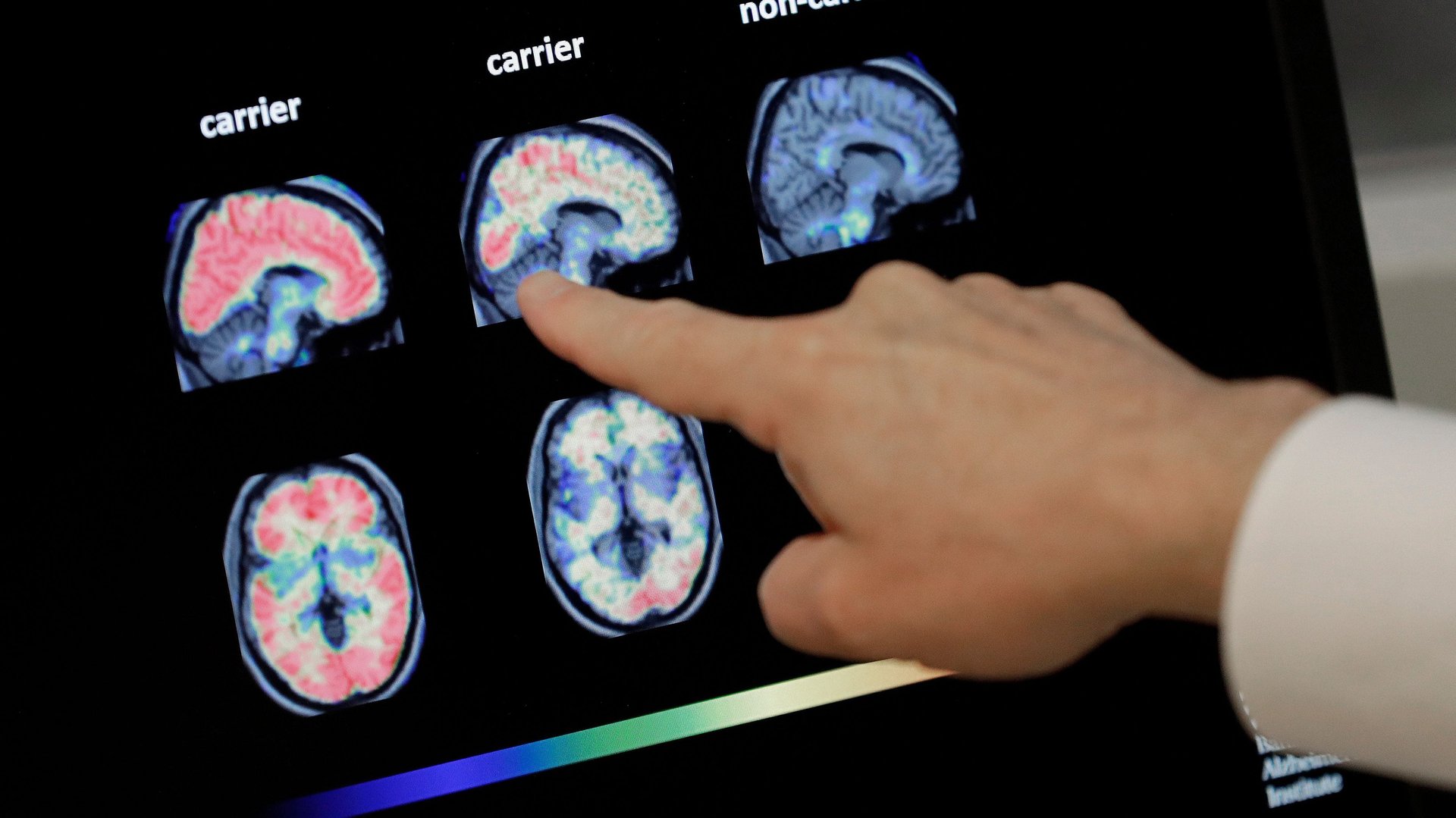

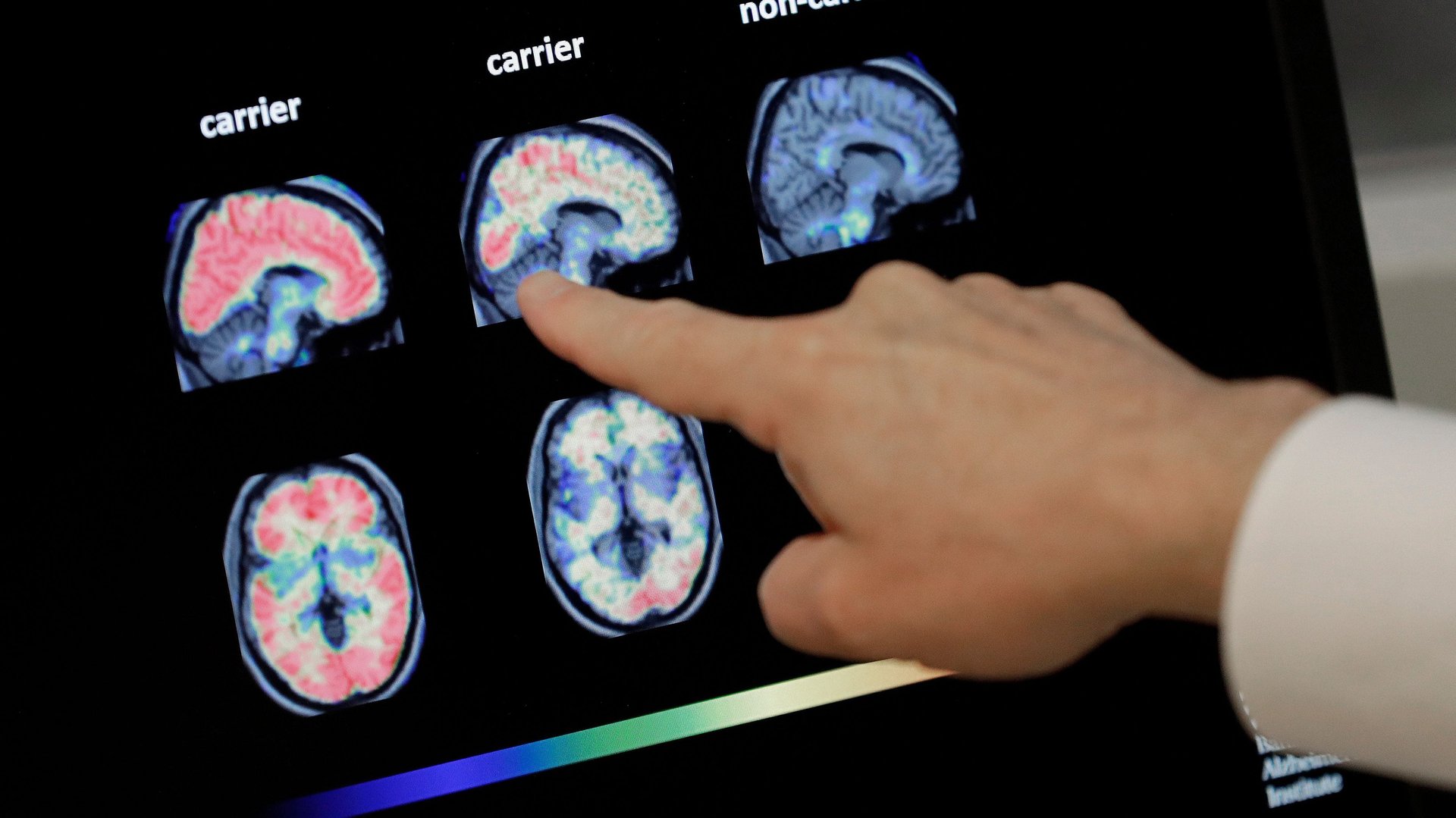

Her work was based on a new type of brain-imaging technology that gives physicians better insight into what’s going on inside people’s skulls. She typically operates from a laboratory at Yale in which she experiments with advanced positron emission tomography (PET) scanners, which can detect biochemical changes in body tissues. In this case, Esterlis studied the brains of 20 people—10 who were diagnosed with clinical depression and 10 who were deemed healthy after completing a comprehensive psychiatric assessment—and found that the brains of those with more severe symptoms of depression showed lower synaptic density.

Synaptic density is important because synapses are essentially tiny bridges that nerve cells rely on to pass their impulses from from cell to the next. A loss of synapses has been associated with neurological disorders, and it’s been found to be common in people between 74 and 90 years old.

All this to say, the research carried out by Esterlis indicates that common byproduct of aging was evident in people suffering from depression. It’s a small study, to be sure, but the outcome was compelling enough to potentially trigger new research into what happens to the brain when a person is depressed.

Researchers at the University of Toronto are working on a drug that appears to be able to reverse memory loss linked to depression and aging. The scientists behind that work also presented at the conference in DC, according to the Financial Times (paywall). That work is still in its early stages—being tested only on mice—but it could wind up solving the very problem that Esterlis’s work is uncovering.