This robot wants to help you control your emotions

For more on new technology that can retrain the mind, check out the first episode of Should This Exist? the podcast that debates how emerging technologies will impact humanity.

For more on new technology that can retrain the mind, check out the first episode of Should This Exist? the podcast that debates how emerging technologies will impact humanity.

Woe is we. Humans are an emotional lot, feeling some type of way all the time. Ironically, talking to a bot—a machine bereft of sentiment, a virtual therapist—might help us learn to deal.

Sure, it sounds weird. How can an app help us make sense of what is most human about ourselves, our sturm und drang? Through illumination, arguably, by shining a light on our mood and thought patterns, thereby creating better mental health habits.

A bot cannot really talk to you, of course, but it can call your attention to the way you converse with yourself, and perhaps in time shift your own relationship with angst. That’s the notion behind the Woebot, an app created by Stanford research psychologist Alison Darcy that aims to make emotional mindfulness available to the masses. (That is, to anyone with a smartphone with a data plan and an Apple App Store or Google Play account—and access to a translation program if they don’t read English, which Darcy has been told by some international users is how they interact with the bot. There are no plans at this time to expand into other languages as Woebot, like most artificial intelligences using language, is still mastering the nuances of its “mother tongue.”)

The Woebot launched in June of 2017 and since then it has averaged about one to two million messages per week and reached people in 130 countries, according to its creator. It appeals equally to male and female users, she notes.

Darcy hopes to “make great psychological tools radically accessible,” she tells Caterina Fake on the podcast Should This Exist? The psychologist argues that this tool teaches people to treat themselves, psychologically speaking, so that they can understand and redraft the damaging narratives that replay continually in their minds. And she might just be right.

DIY therapy

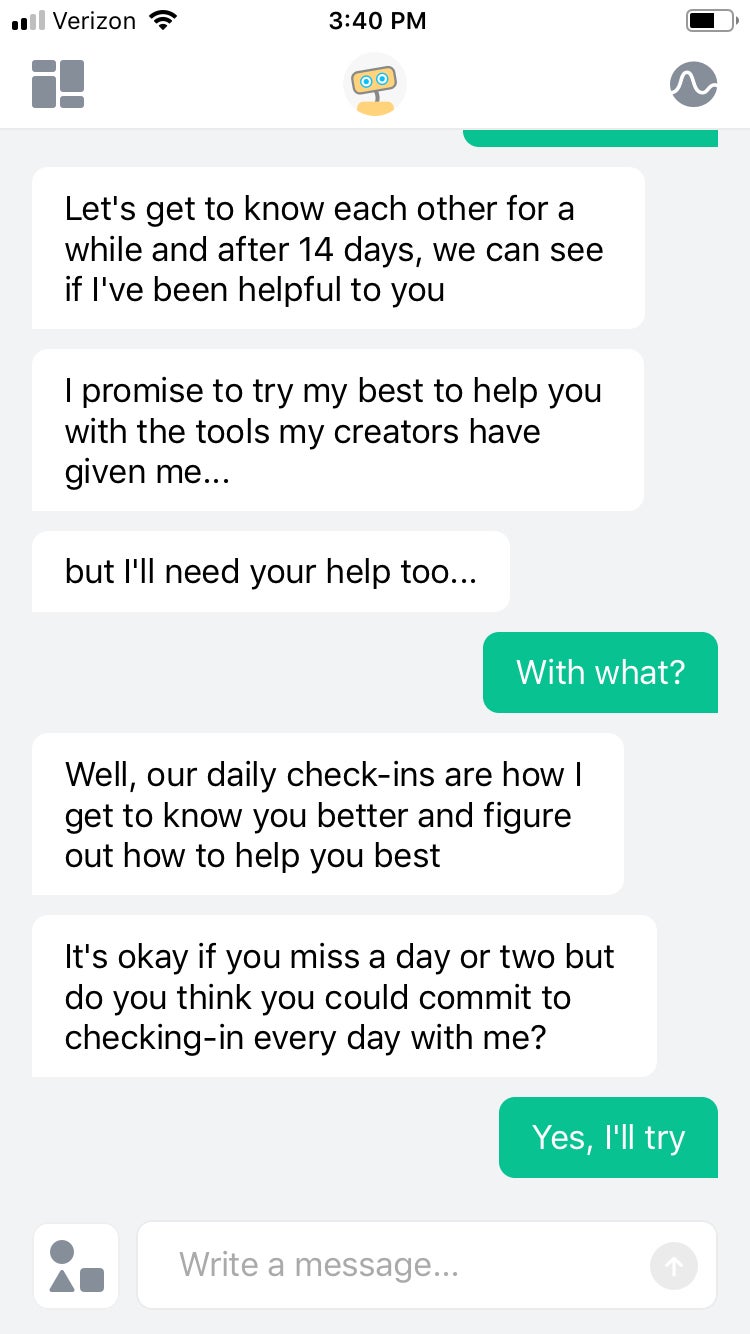

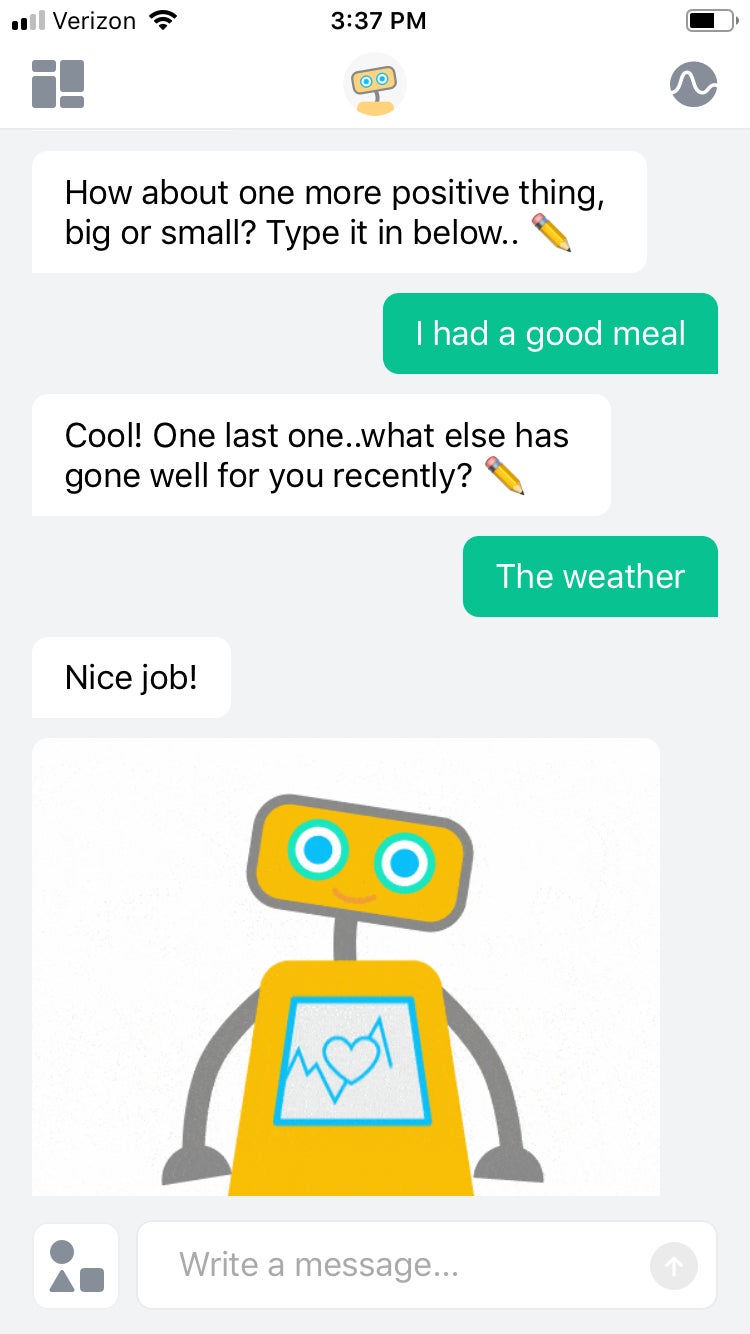

Here’s how Woebot works. First, you sign up for an account. Then, you meet the machine, which is clearly quite pleased with itself and assures you of all it can do for you. Built using natural language, the machine doesn’t “understand” what you’re saying or respond to your specific statements necessarily but it follows a script written by its creators that corresponds, more or less, to what a conversation with a person would sound like and manages to provide a sense of exchange, albeit a somewhat imprecise one. Dubbed a “self-care expert,” the virtual therapist’s “voice,” its written style, is that of a chatty, cheerful, and empathetic millennial, someone who favors emoji, exclamation points, and the informal postmodern patois of tech platforms. It types things like, “hey” and “cya later” and “no problemo,” undermining the impression that it’s taking your woes seriously (which it isn’t, of course, because it’s a program and not a person capable of seriousness).

Nonetheless, the Woebot won me over, and here’s why. It provides useful exercises that you could arguably apply even when the bot’s not on.

For example, it asks how you feel—offering a slew of choices accompanied by emoji, like sad, happy anxious, etc.—and responds accordingly. So, if you choose “anxious,” say, as I did in my experiment today, it replies, “I’m sorry to hear that E.” Then it asks if you just wanted to share the sentiment or wish to address the emotion. If you choose to consider it further, the bot prompts you with questions that force you to examine and attempt to reframe your thoughts and feelings.

For example, the bot prompted me to type three thoughts arising from my claimed anxiety. I wrote, “So much could go wrong. Trouble ahead. No rest for the weary.”

The bot then urged me to rewrite one of these thoughts and to consider whether anxiety ever had upsides, like alerting one to possible problems.

Next, it provided a brief lesson on the power of language in the context of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). This mode of treatment for anxiety and depression, CBT, calls attention to thinking patterns and teaches patients to recognize and address their negative tendencies and limiting beliefs with exercises.

It tries to literally change your mind by providing perspective and cultivating attention until you have replaced bad habits with better ones. As Darcy puts it on Should This Exist?:

This is a key concept from from cognitive behavioral therapy, that there’s a sort of running narrative in your mind and it is particularly loud and articulate, like the inner critic, right? And CBT teaches you to tune into those voices and then write them down. There’s something very impactful in actually externalizing those thoughts and writing them down—or in this case typing them, telling Woebot.

As the Woebot explained in my “DIY therapy” session, the language we use shapes our experience of the world, so we have to choose our words and thoughts carefully. And though the machine—the fact that it wasn’t human—was irritating me by virtue of its automated nature, I was also forced to concede that this type of mindfulness tool might indeed be effective. Despite its relentless chipper-ness that doesn’t seem entirely appropriate given the therapeutic context, and the fact that it’s a little self-involved—the Woebot continually returns to the topic of its abilities—it does make you articulate your thinking, and that’s a good thing.

Because, of course, along with my thought “so much could go wrong” is the equally legitimate notion that some things could go right. Typing it did solidify the thought and if I had not already spent decades training myself in reframing via other methods, I could certainly have benefited from the bot’s prompt. It can’t hurt to have a daily reminder to reconsider one’s thinking.

Old school

There are other methods to cultivate self-awareness besides the Woebot. Classics include meditation, therapy with a fellow human, reading, and journaling to name just some. But for those who are into apps, having an app for that probably isn’t bad.

CBT as a therapy is popular but has its detractors. Rather than casting about in the past for the roots of malaise like the traditional talk therapy made famous by Sigmund Freud, CBT gets straight to the here and now. The treatment is focused on reshaping thought in the present, not getting to the root cause of psychological problems and the situations that led you to adopt negative thought patterns in the first place. It has a practicality and efficiency that’s not only appropriately postmodern but also rooted in ancient practices.

Just as the meditating Zen master learns to watch thoughts arise and pass and with this experience becomes detached from emotion, so does CBT teach that feelings are fleeting and malleable. Meditation is perhaps the oldest method developed to study the self and cultivate skills to predict mood signals. Meditators develop their own personal datasets which they employ to manage moods, just as the Woebot promises to collect intelligence on your thinking patterns.

Lisa Feldman Barrett, a neuroscientist and psychology professor at Northeastern University, in a 2017 Ted Talk explained her conclusions after 25 years of scientific research on emotions and the brain: “[Emotions] are guesses that your brain constructs in the moment where billions of brain cells are working together, and you have more control over those guesses than you might imagine that you do.”

In other words, when we feel we’re unconsciously predicting what might be, based on past experiences. Feldman Barrett argues that we can retrain the brain with exercises and awareness to predict less anxiously and thus become happier, healthier humans. And that’s what the Woebot aims to do, too, cultivate that awareness and provide the exercises that might make your predictions more positive and effective.

Machine people

Yet there are potential risks to chatting with a bot about problems. For one thing, it means becoming even more reliant on devices we’re already having trouble putting down. It’s also notable that this kind of interaction with technology could contribute to eroding socialization. Could we someday become people who prefer to interact with machines rather than our own flesh and blood kind? Will we share all our troubles with technology and feel no need for human exchange?

Arguably, yes, if the affection that some elderly Japanese people feel for Paro, a therapy robot modeled after a baby harp seal is any indication. Some patients refer to the circuitry as their baby, as a 2010 New York Times (paywall) article noted. And it may be easier to share your stress with a non-judgmental nonentity than friends, family, or mental health professionals, especially if you’re a person who spends all your time online and has come to find personal interaction offensively intimate.

But it’s more likely that Woebot will work like telemedicine—which allows rural patients and doctors to consult with specialists onscreen rather than in person—supplementing the work of human healers. After all, the Woebot is limited in its abilities. And it can’t actually replace human contact. It can just make humans who use it more aware of the emotions they experience and how to deal with them, which should improve the quality of their own thinking and their interactions with other people. Plus, practicing thinking about emotions in a more constructive fashion on the app can over time create good mental habits that you might apply even as your thoughts arise, whether or not your phone is in tow. “It’s not a replacement for human connection, but it’s one step forward to just stopping the negative spiral, so they can just get back on with their lives,” Darcy contends.

New school

Notably, we are already talking to machines and telling them our secrets. People confide in Siri—as a result, Apple has been looking for tech types with a counseling bent to help engineers program an electronic assistant who can respond empathetically and effectively to these disclosures. An April 2017 ad for a “Siri Software Engineer, Health and Wellness” in Santa Clara, California explains, “People talk to Siri about all kinds of things, including when they’re having a stressful day or have something serious on their mind. They turn to Siri in emergencies or when they want guidance on living a healthier life.”

Woebot is that electronic assistant, only more focused, devoted entirely to your emotions. It will prompt you about your feelings every day, remind you to write in a gratitude journal, provide you with some basic psychological knowledge that can inform your understanding, and help you to create a habit of reflection rather than reaction.

And it’s just one of many technologies that attempts to address our inner state. A number of new tools, many still in development, try to predict emotions based on certain biomarkers. Psychologists and technologists are trying to build emotional databases that teach machines how to read human feelings by compiling a bunch of data about biological signals that indicate impending changes in order to digitally predict moods. Your wristband or phone would serve as a sensor, helping you ward off depression, supporters of the new technology say. “I suffered from depression early in my career and I do not want to go back there,” Rosalind Picard, an electrical engineer and computer scientist at MIT, tells Nature. “I am certain that by tracking my behaviors with my phone I can make it far less likely I will return to that terrible place.”

The goal is noble. However, there’s a wider danger of privacy invasions with all this collection of emotional data, warned Yaniv Altshuler of the MIT Media Lab in MIT Tech Review in 2014. He helped pioneer “reality mining” smartphones as an approach to studying human behavior and argues that there will be downsides to mobile data troves, perhaps not all of which technologists can now predict.

Given what we know from other contexts, Altshuler’s likely right. Data which seem innocuous can end up finding uses that violate legal protections. Take cell phone location data, which providers collect from users’ devices and which do not reveal substantive information about conversations, for example. For years, law enforcement authorities were able to request this data from corporations by arguing that it wasn’t private information although in fact data about users’ locations, when put together, does tell a story that would otherwise not be available. Last June, the US Supreme Court ruled that law enforcement needs a warrant to see these data because the cumulative effect of the collection is substantive and constitutionally protected after all.

Darcy argues that Woebot only uses the data it collects to inform its artificial intelligence. She doesn’t anticipate ever selling data and notes that, to the extent information is kept, it’s anonymous. Technically speaking, the machine “learns” how to interact as it integrates more information, and someday

Relentlessly available

For the inventor what matters most is that Woebot can bring cognitive behavioral therapy to the many. Woebot can chat with more “patients”in a day than a therapist can see personally in a lifetime and it’s available to people in places where there are no mental health services. She notes that in Zimbabwe, for example, there are only nine psychiatrists nationwide—and she’s heard from Woebot users there who say they benefit from their automated exchanges.

So though the psychologist concedes that Woebot’s got limits—it cannot have a super deep conversation with a patient, like a human therapist—it’s also capable to what humans are not able to offer. It can chat at any hour of the day or night and reach people almost anywhere in the world, and it can empower individuals to help themselves.

Darcy understands why people are skeptical of her invention, but she believes it’s a useful addition in the realm of mental heath, rather than a replacement for traditional methods. She says, “You know, it’s like sometimes you just need a wrench to fix your leaky faucet, and then sometimes you need a plumber. It’s about knowing the difference.”

Should This Exist? is a podcast, hosted by Caterina Fake, that debates how emerging technologies will impact humanity. For more in-depth conversation on evaluating the human side of technology, subscribe to Should This Exist? on Apple Podcast.