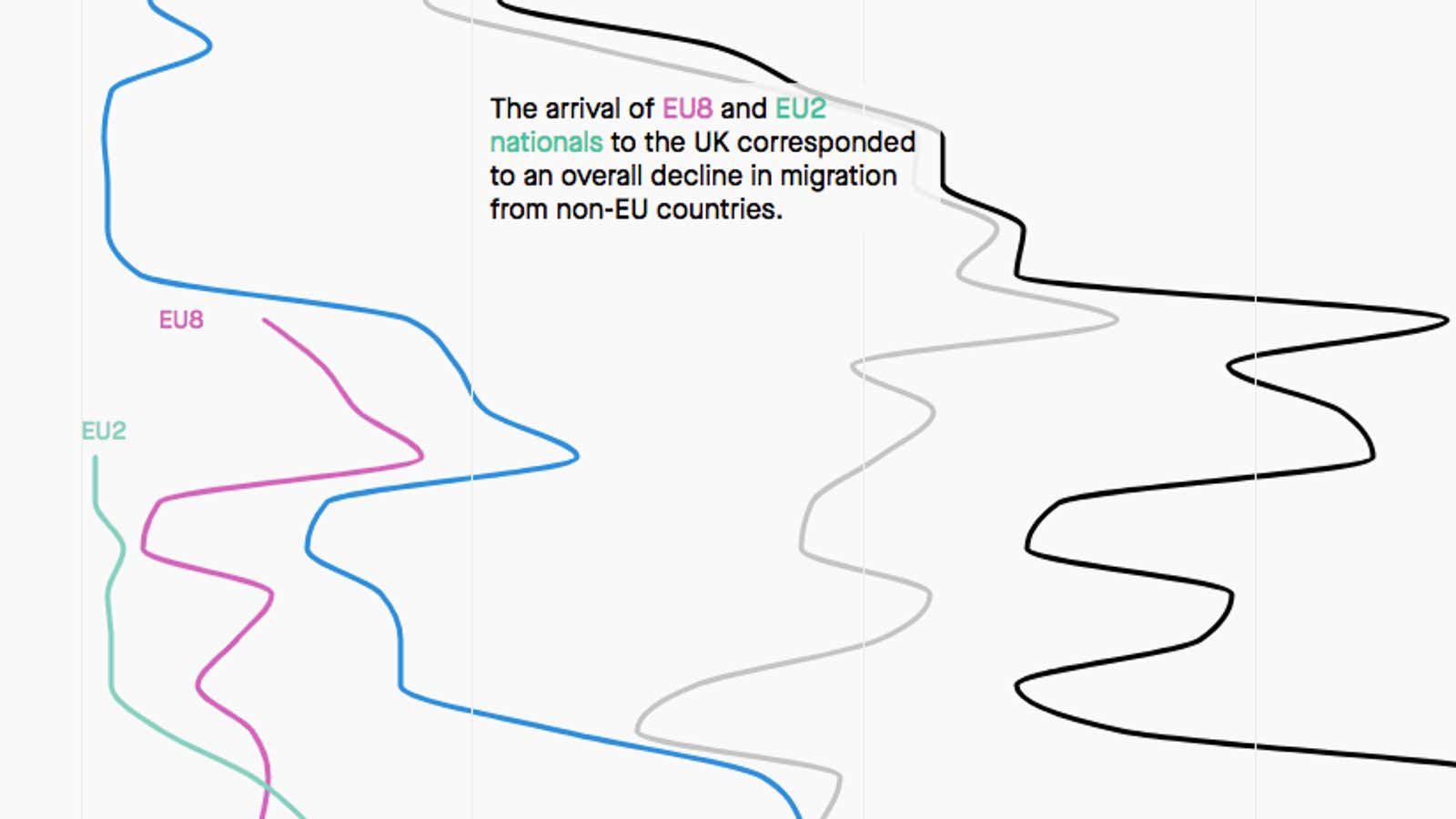

When 52% of Brits voted for the UK to leave the EU in 2016, one of the messages it sent was that Europeans were not nearly as welcome as before. Indeed, two years on, the net migration 1 of EU nationals to the UK has fallen to its lowest levels since the 2008 global financial crisis, according to data from the Office for National Statistics.

Membership in the EU allows citizens to live and work anywhere within the bloc. The pro-Brexit campaign slogan of “Take Back Control” emphasized ending this practice, playing on the unease that many felt when immigration to the UK boomed after the EU expanded in 2004.

Eastern European immigrants from eight of the 10 nations that joined the EU in 2004 (EU8) 2 were subject to particular hostility in the years just before and after the Brexit referendum. Bulgaria and Romania (EU2) joined the EU in 2007, and Croatia in 2013. The far-right UK Independence Party saw its membership grow in areas with the largest number of Eastern European migrants.

As the referendum approached, media coverage inflated the scale of migration and relied on stereotypes about EU nationals abusing the welfare system and straining the housing market. The austerity measures imposed after the global financial crisis in 2008 stoked these fears.

It was in this climate of economic anxiety, austerity fatigue, and concern over a perceived loss of national identity that made the desire for greater control over immigration—and often blatant xenophobia—a vote-winning strategy. Immediately before the referendum, nearly half of Brits said immigration was the biggest issue facing Britain. Immediately after the vote, net migration from the EU began to drop, and it continues to today.

Immigrants from Europe—and in particular from the EU8—have got the message. While net migration to the UK has remained relatively stable overall, migration from other EU countries is now the lowest in a decade. For the first time since they joined the EU, more citizens from Eastern Europe have left the UK than arrived.