Is RBS Europe’s most accident-prone bank?

RBS can’t seem to do anything right lately. The British lender, still majority owned by the state following a massive bailout five years ago, has (to borrow a phrase from a popular children’s book) suffered a series of terrible, horrible, no good, very bad days. The reverse chronology:

RBS can’t seem to do anything right lately. The British lender, still majority owned by the state following a massive bailout five years ago, has (to borrow a phrase from a popular children’s book) suffered a series of terrible, horrible, no good, very bad days. The reverse chronology:

Dec. 11: RBS pays $100 million to settle allegations that it violated US money-laundering rules. Seized documents appear to show step-by-step instructions for bank staff on how to alter payments to avoid detection.

Also Dec. 11: Finance director Nathan Bostock resigns after only 10 weeks on the job.

Dec. 4: RBS is fined €391 million ($538 million) by the EU for its part in a cartel that rigged benchmark interest rates in yen and euros.

Dec. 2: A technical glitch shuts down all payments and withdrawals from RBS cards for hours. The bank’s boss admits that, “for decades, RBS failed to invest properly in its systems.”

Nov. 25: The bank publishes a report it commissioned on its small business lending practices, highlighting both shortcomings and strengths. But on the same day, a scathing report by an adviser to the government alleges that a special division at RBS purposefully pushes some small business borrowers into default in order to buy their property on the cheap. The UK’s financial watchdog opens an informal investigation of the bank’s lending practices based on the reports a few days later.

Nov. 7: RBS pays $154 million to US regulators to settle charges it misled investors in residential mortgage-backed securities.

Nov. 1: RBS reports a £828 million quarterly loss and warns of “substantial” losses to come, thanks to the creation of a “bad bank” to house £38 billion of its riskiest assets. Although this allowed the bank to avoid a break-up, it struck some as more of a rebranding than a true restructuring. Its shares drop by nearly 8% on the day.

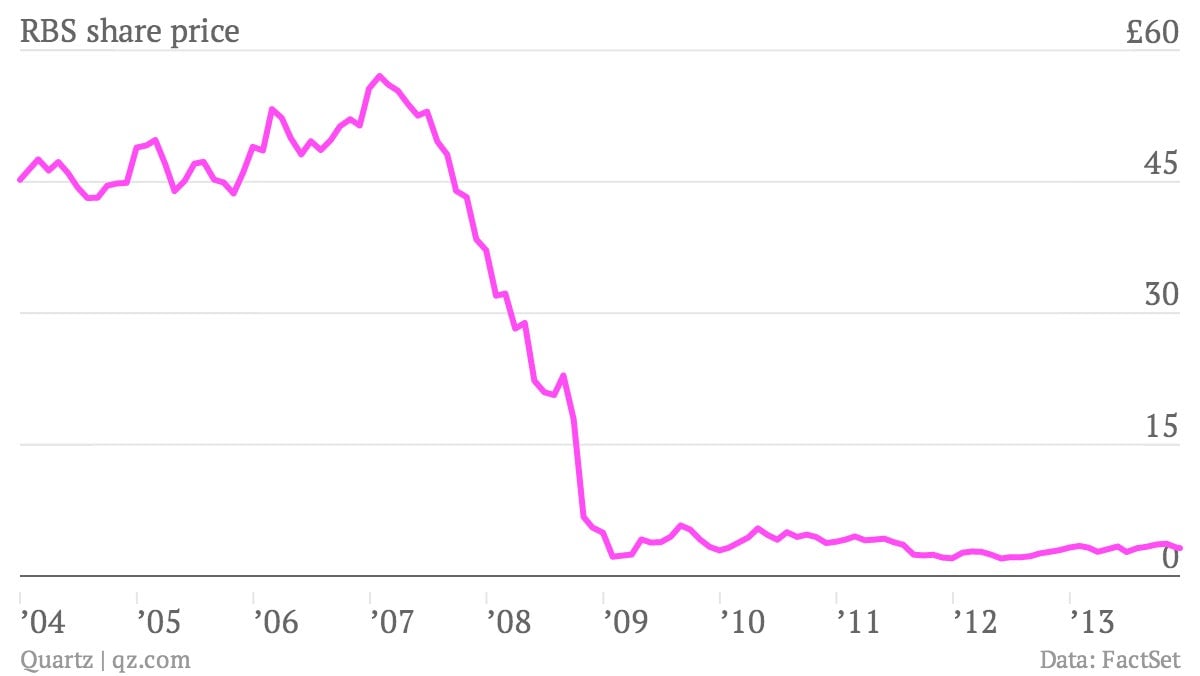

RBS’s shares are currently down by around 14% since November. They also sit some 40% below the government’s break-even price on the stake it acquired in its 2008 bailout (around £5 per share). This price is itself a small fraction of the value RBS once commanded before it ran aground during the crisis, and continues to stumble from one disaster to the next.