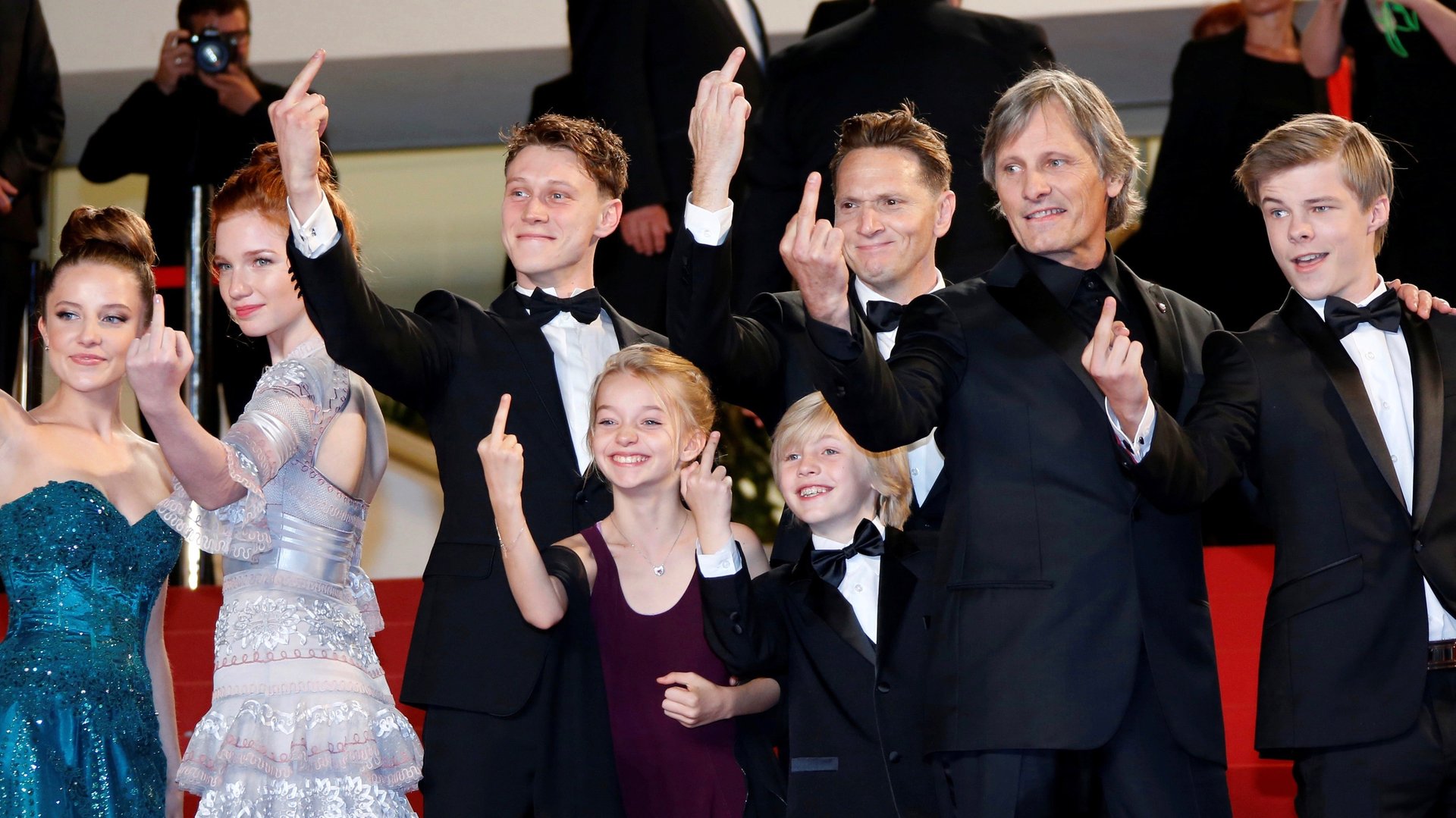

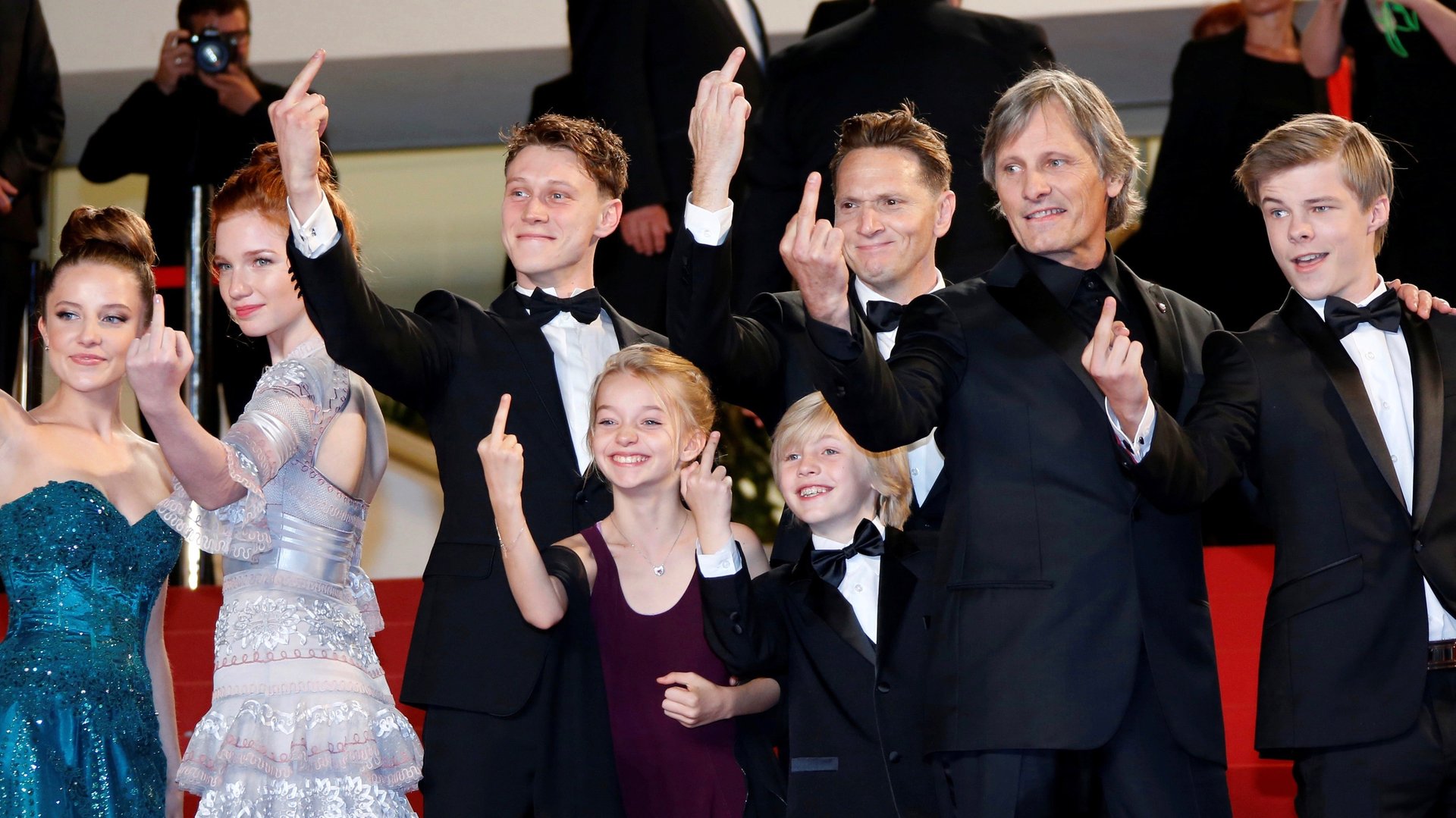

A US court affirms your right to flip the bird to cops

It’s probably not a good idea to give any authority the middle finger. But if you’re in the US and want to express yourself crudely, your right to do so has been affirmed by a panel of three judges in a charming Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals opinion issued on March 13 (pdf).

It’s probably not a good idea to give any authority the middle finger. But if you’re in the US and want to express yourself crudely, your right to do so has been affirmed by a panel of three judges in a charming Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals opinion issued on March 13 (pdf).

“Fits of rudeness or lack of gratitude may violate the Golden Rule. But that doesn’t make them illegal or for that matter punishable or for that matter grounds for a seizure,” writes judge Jeffrey Sutton in Debra Lee Cruise-Gulyas v. Matthew Wayne Minard.

The decision stems from a June 2017 traffic stop that gave rise to complex constitutional law claims. Minard is a Michigan cop who pulled over Cruise-Gulyas for speeding. He gave her a ticket for a lesser, non-moving violation, thinking he was doing her a favor. She repaid the officer by flipping him the bird after their encounter was over, while she was driving away.

Miffed by this gesture, Minard retaliated. He pulled Cruise-Gulyas over again to adjust the initial ticket and issue a speeding violation.

This time, Cruise-Gulyas did much more than give the officer the middle finger. She sued Minard for violating her constitutional rights, arguing that he unreasonably seized her in violation of the Fourth Amendment, retaliated in violation of the First Amendment guarantee to free speech, and restricted her liberty in violation of the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment.

Minard, in turn, moved to dismiss the case based on a concept called “qualified immunity.” He argued that police officers can’t be sued for what they do in a professional capacity. And that’s true—as long as the officer doesn’t violate a person’s clearly established constitutional or statutory rights. In other words, if a legal question is unsettled or the facts of a case are in dispute and an officer possibly violated rights, they can’t be held liable for making reasonable but mistaken judgments about open legal questions. But when a violation has clearly occurred—like retaliating for flipping the bird—police may still be liable. A lower court denied Minard’s motion to dismiss.

The police officer appealed, arguing that even if he violated Cruise-Gulyas’s constitutional rights, those rights weren’t so clearly established that he didn’t deserve the protections of qualified immunity. Basically, he was claiming that it’s not obvious whether an individual can insult an officer by giving them the middle finger. The appeals court, however, strongly disagreed with this argument, citing a slew of cases where citizens flipped off cops that show the gesture is “crude but not criminal.” As Judge Sutton noted, “This ancient gesture of insult is not the basis for a reasonable suspicion of a traffic violation or impending criminal activity.”

The judicial panel concluded that Minard had no basis for pulling Cruise-Gulyas over a second time to adjust her ticket. That second stop was a violation of her Fourth Amendment right to be free of unreasonable government searches and seizures and was premised on an exercise of her free speech rights. “No matter how [Minard] slices it, Cruise-Gulyas’s crude gesture could not provide that new justification” the officer needed for the second traffic stop which gave rise to the constitutional claims, according to the court.

By issuing a more severe ticket based on the vulgar gesture, the officer was chilling free speech and trying to deter Cruise-Gulyas from expressing herself similarly in the future, the court ruled. And that’s not cool. As the opinion explains, “Any reasonable officer would know that a citizen who raises her middle finger engages in speech protected by the First Amendment.”