The college application process is an ethical test—and many parents are failing it

Since 2013, Making Caring Common, an initiative from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has tried to make the college admissions process saner. It has encouraged admissions officers to prioritize not the quantity of students’ achievements but rather the quality of their ethical and academic engagement to make the admissions process more fair.

Since 2013, Making Caring Common, an initiative from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has tried to make the college admissions process saner. It has encouraged admissions officers to prioritize not the quantity of students’ achievements but rather the quality of their ethical and academic engagement to make the admissions process more fair.

In a recent report (pdf) released ahead of schedule, the project shines a spotlight on the role parents and high schools play. The college admissions process is an ethical test, and many parents and high schools are failing, write the authors, led by Richard Weissbourd, a psychologist who founded Making Caring Common.

“College admissions may well be a test for parents, but it’s not a test of status or even achievement—it’s a test of character,” the report states.

Too often parents turn to high-priced tutors to bolster their kids’ scores and write their essays for them. Sometimes they also seek to sabotage other teens’ efforts in a bid to secure a place for their own offspring.

“In an effort to give their kids everything, these parents often end up robbing them of what counts,” says the report.

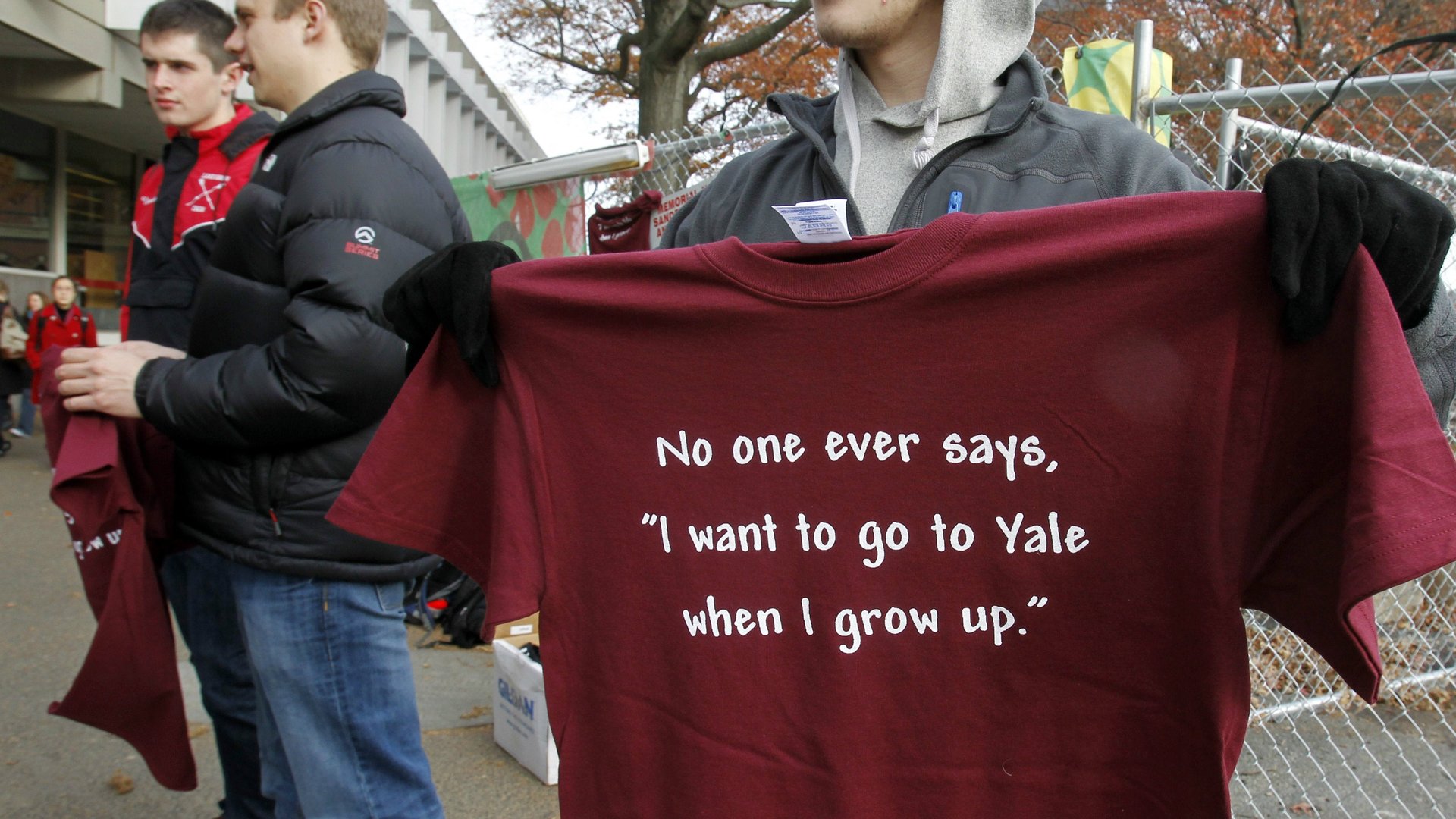

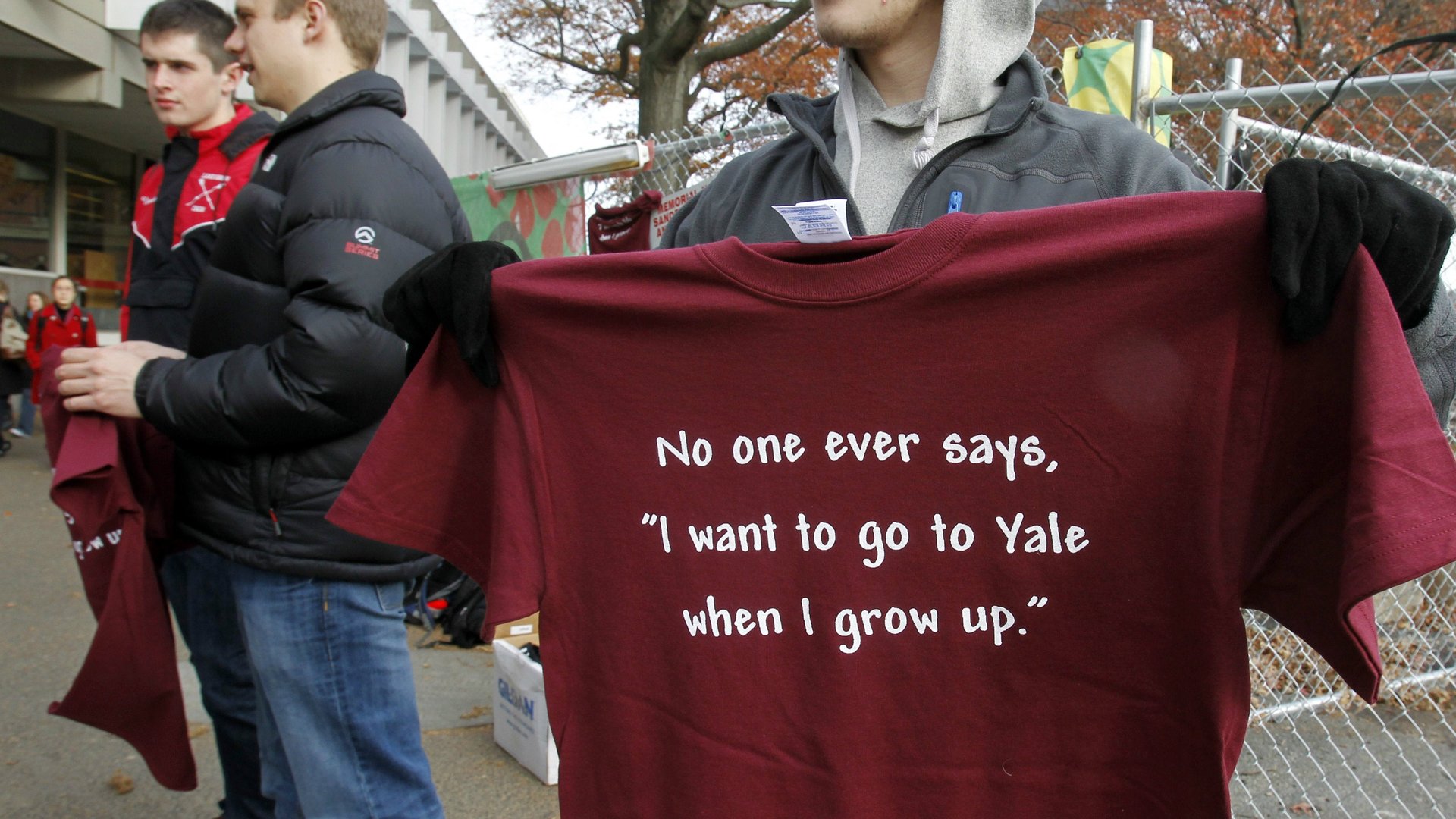

The study does not spare high schools, saying they “do little to challenge parents engaging in ethically troubling behavior.” In focusing too much on a handful of selective colleges, they fail to learn who the kids really are and what might be best for them.

The authors didn’t intend to release the report so soon, but they rushed it out after the Justice Department charged 50 people, including 33 parents, in a brazen bribery scheme to help kids cheat on exams, or pretend they were star athletes, to get into elite universities. Weissbourd, who has spent years on the thorny problem of how to make college admissions more fair and take pressure off kids, says one of his greatest fears is that parents will see the scandal and write it off as unrelated to them.

“I fear that parents won’t see themselves in this,” he says. Of course, the alleged bribery ring was both illegal and “mind-bogglingly unethical and dumb.” But the lack of consciousness about equity? He argues that’s way more common. Helping kids write their college essays, allowing them to fudge their extracurriculars or volunteering, hiring high-priced tutors to help with the applications? “It gives their kids unfair advantages,” he says.

He cites a survey from this month’s report in which parents say they prioritize caring over achievement, but estimate that other parents significantly prioritize achievement over caring. Believing that makes it easy to justify an at-all-cost mentality

Some see little connection between breaking the law and being (legally) ambitious. But the focus of Weissbourd’s work is not to stop parents from helping, but to stop them from doing everything they can—even if it’s ethically dubious—to give children a leg up. Ambition is fine—it should just come from the kids, not the parents.

“The essence of being ethical is attending to equity and fairness in every aspect of your life, not doing that selectively,” he says. “College admissions should not be an exception.”

The report cites research showing that qualities including empathy, self-awareness, gratitude, curiosity, the ability to understand multiple perspectives, and a sense of responsibility for one’s communities “are at the heart of both doing good and doing well in college and beyond.”

But that’s not always what parents or schools prioritize. They often focus more on what it takes to get in, falling back on the excuse that “everyone is doing it” and “it would be unfair to my child not to help.” If the stakes are high, they reason, it’s OK to do what it takes.

Weissbourd, as well as most child psychologists, would agree this is simply false (never do for a child what they can do for themselves) and hurts the kids, as well as the admissions process.

The reports offers advice, including some obvious yet often ignored points:

- “Keep the focus on your teen.” It’s not about you.

- “Follow your ethical GPS.” They are learning from you through the process. What will they learn?

- “Use the admissions process as an opportunity for ethical education.”

- “Be authentic.” Have honest conversations about what is happening (i.e., “I am not writing your essay,” and why).

- “Help your teen contribute to others in meaningful ways.” They do not need to found an orphanage in a poor country to check the community service box.

- “Advocate for elevating ethical character and reducing achievement-related distress.” Tell schools that five advanced-placement courses is too many for most 16-year-olds.

- “Model and encourage gratitude.”

Most of us parents want the best for our kids. And many of us are plenty ambitious enough, for ourselves and our kids. That’s nothing to be ashamed about. But we should not crowd out their ambition with ours. As the report says: “Is getting into a particular college really worth more than compromising our teen’s or our own integrity?”