Why Congress has a right to the full Mueller report

Donald Trump is pushing for Congress and American voters to move on from Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, tweeting recently that “it is time to focus exclusively on properly running our great country.”

Donald Trump is pushing for Congress and American voters to move on from Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, tweeting recently that “it is time to focus exclusively on properly running our great country.”

Yet American history shows that the filing of a special counsel’s report usually marks a midway point into any investigation of presidential misconduct, not the end. Case in point: the House Judiciary committee voted April 3 to issue a subpoena to compel the Department of Justice to turn it over.

In both the Watergate investigation of Richard Nixon’s 1972 re-election campaign and the Kenneth Starr investigation that uncovered Bill Clinton’s sexual misconduct, the information gathered by the special counsel was provided to members of Congress and used to shape impeachment investigations and public hearings. In his handling of the Mueller report, historians and legal experts say Trump’s attorney general William Barr is conflating what information the American public can see with what Congress is entitled to see.

Since issuing his summary of Mueller’s key findings on March 24, Barr has told House and Senate leaders his office is reviewing the full report and will redact material that cannot be legally made public by federal code (referring to information from grand jury proceedings), would compromise intelligence sources and methods, would affect ongoing federal investigations, or would “unduly infringe on the personal privacy and reputational interests of peripheral third parties.”

A growing number of scholars and attorneys say Congress—which has a constitutional requirement to oversee and constrain presidential abuses of power and threats to the national security of our elections, as well as determine when impeachment is warranted—should receive the entire report, and have access to all the underlying information.

Additionally, Adam Schiff, the Democratic chair of the House Intelligence Committee, and Mark Warner, the Democratic vice-chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee “should demand the unredacted report for their own committees,” writes Nelson W. Cunningham, a former federal prosecutor and a White House counsel to Bill Clinton, in Politico. Congressional intelligence committees are entitled to it by statute, he states, and there is no legal bar against sharing information that is provided to intelligence officials with congressional intelligence chairs.

To illustrate the differences between the way the special counsel investigations of Nixon, Clinton, and Trump unfurled, Quartz compared how prosecutors’ information made its way through the Justice Department, to Congress and into the public eye, in the days and weeks after reports were completed.

The special prosecutor files a report

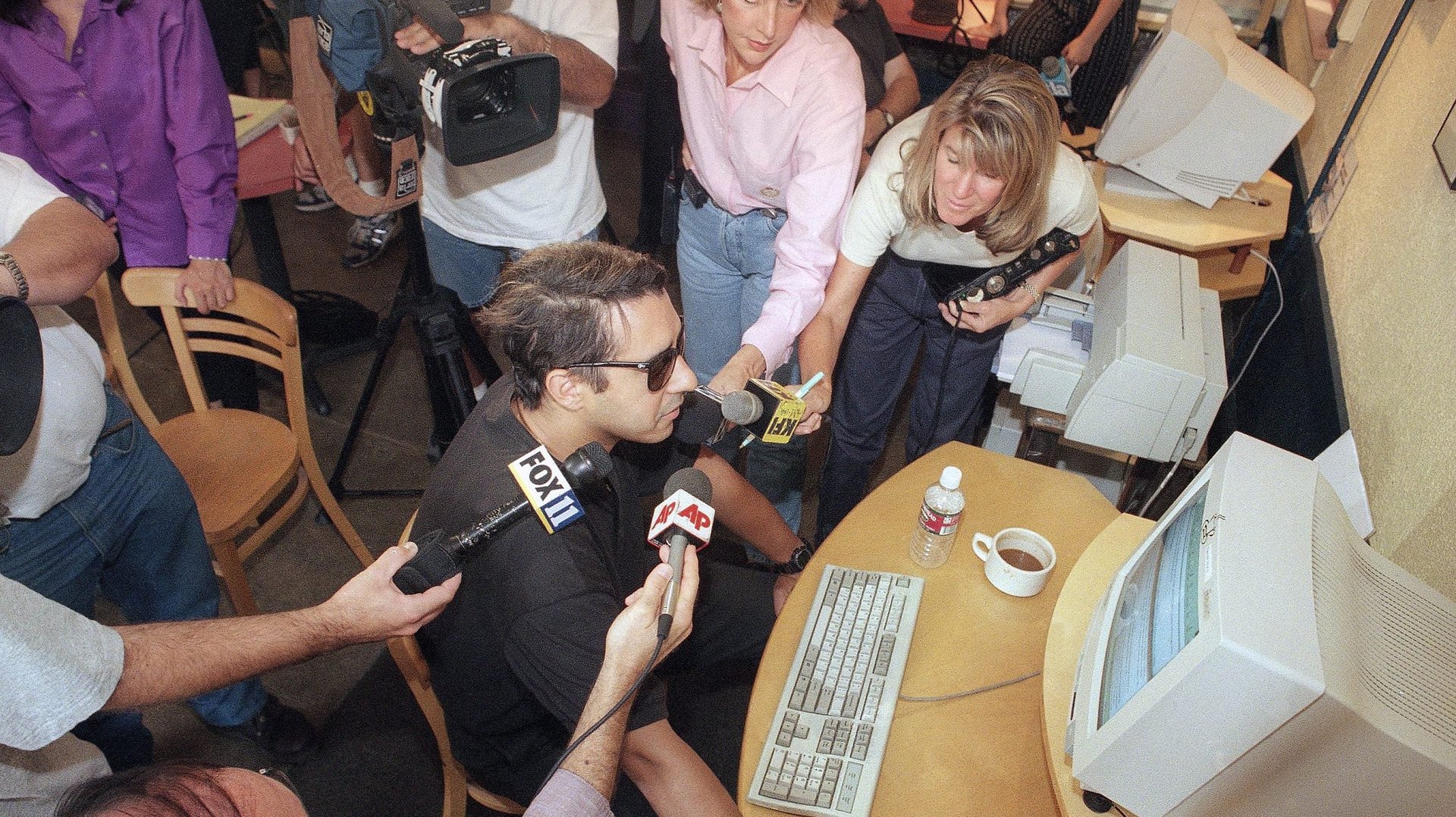

Robert Mueller

Mueller files his report to Barr on March 22, 2019 after an investigation of 674 days. The delivery was announced by the attorney general in a letter to Congress. Mueller’s investigation produced 27 indictments and seven guilty pleas. Those charged along the way included six Trump advisors and 26 Russian nationals. There was intense speculation about what Mueller’s final report might say about Trump, his family and other close associates. Barr’s summary says Mueller closes his probe by saying there would be no further indictments sought, foreign or domestic.

Kenneth Starr

Starr’s report is filed on Sept. 9, 1998 directly to members of the Republican-led House, after a four-year investigation marked by multiple leaks to the press, some from future Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh, who served as associate independent counsel. The report says it finds “substantial and credible information…that may constitute grounds for impeachment” of Bill Clinton. The probe was a continuation of an investigation into whether Bill and Hillary Clinton benefited from money funneled into the Whitewater Development Corporation, an Arkansas real-estate firm they formed with friends. After Whitewater special prosecutor Robert Fiske, a Republican, found no evidence of wrongdoing in 1994, Starr was unexpectedly chosen to replace him by a three-judge panel.

The rules about to whom special prosecutors file their reports were changed afterward, in part because the Clinton White House said the Starr report was full of “irrelevant and unnecessary graphic and salacious allegations” designed to “damage the president.” Clinton’s attorney general Janet Reno put new regulations in place after Starr the report that required any subsequent special-counsel investigation to be delivered first to the attorney general, not Congress.

Leon Jaworski

Jaworski’s investigation results in a March 1, 1974 indictment of seven members of Nixon’s administration for conspiracy in covering up the Watergate scandal. The charges are presented to chief judge John J. Sirica of the US District Court for the District of Columbia in a “sealed report, accompanied by a bulky briefcase reportedly containing information about Mr. Nixon’s role in the Watergate affair,” the New York Times reported at the time. That’s believed to include the 55-page “Watergate road map” that lays out in simple language why a grand jury indicted Nixon co-conspirators in the Watergate break-in, and why they had concerns about Nixon’s actions, which was also dated March 1, 1974.

Because Jaworski didn’t believe a sitting president could be indicted for obstruction of justice, he didn’t write a report coming to any conclusion. The “road map” itself is signed by a grand jury foreman. Jaworski’s investigation was a continuation of a previous special counsel investigation that began in May 1973. After special counsel Archibald Cox demanded Nixon turn over White House recordings of his conversations with campaign officials, he was fired by Nixon’s solicitor general Robert Bork in the “Saturday Night Massacre.” (In 1978, the Ethics in Government Act passed in response to Cox’s firing created the idea of a three-judge panel, the entity that ultimately resulted in the office held by Fiske, the initial Whitewater investigator, being refilled.)

Two days later

Mueller

Barr tells Congress and the public in a four-page letter on March 24, 2019 that Mueller’s investigation “did not establish that members of the Trump campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities,” and that Barr and deputy attorney general Rod Rosenstein had decided not to pursue obstruction of justice charges. Among the reasons Barr cites for not making the entire report public is that it contains grand-jury testimony.

Starr

The House Rules Committee votes to make the Starr report public on Sept. 10, 1998. The nearly 450-page report is uploaded to the internet the next day, at the insistence of Republican lawmakers, who say the new technology allows Americans to see it as quickly as possible. To prevent government websites from crashing, House Republicans also give copies of the report on diskettes to sites and news organizations including America Online, CNN, and the Associated Press.

Jaworski

The House Judiciary Committee had already voted to investigate whether to impeach Nixon on Feb. 6, 1974. Jaworski’s grand-jury investigation has uncovered information the committee had not seen and the special prosecutor’s office was involved in “intensive discussions about how to proceed,” behind closed doors in early March, Lawfare reports.

Within the next two weeks

Mueller

Barr tells the House and Senate judiciary committees in a March 29, 2019 letter that he will release a redacted copy of the 400-page report to Congress and the public by mid-April. He also offers to testify in front of Congress. Jerrold Nadler, Democratic chair of the House committee, responds by demanding a full, unredacted copy of the report by April 2.

Starr

Some 3,200 pages of underlying grand-jury testimony is released to the public on Sept. 21, 1998, including transcripts of hours of White House intern Monica Lewinsky answering questions and her personal notes to the president addressed “Dear Handsome.” More than four hours of Bill Clinton’s grand-jury testimony is made public, covering everything from books he received as gifts from Lewinsky, to explicit details of their sexual relationship, to her later job at the Pentagon.

Jaworski

Negotiations continue behind the scenes on whether the Watergate road map and the information related to it should go to the House committee.

Lawyers for H.R. Haldeman, Nixon’s former chief of staff, one of the indicted “Watergate seven,” send a letter to Sirica on March 4, 1971 and then appear before him on March 6, 1971, arguing that the “bulging suitcase” mentioned in press reports of includes grand-jury testimony that should be sealed. On March 21, 1974, the US District Court of Appeals rules that the Jaworski information should be supplied to the House, ultimately supplying members with the underlying intelligence that provides a step-by-step guide to conduct public hearings and bring charges against Nixon.

Two months and beyond

Barr

It remains to be seen. Barr has promised to deliver a redacted report to the public and Congress, by “mid-April,” and offered to testify publicly to Congress in early May. In addition to Nadler’s subpoenas to get the report, Congress may call witnesses who testified in front of a grand jury in the Mueller investigation, to learn what they said behind closed doors as part of several ongoing investigations into Russian interference in the 2016 election, Trump’s business dealings, and White House foreign-policy decisions. Separately, federal prosecutors in the Southern District of New York are investigating possible Trump campaign-finance violations.

Starr

Clinton is impeached by the House, which charges him with perjury and obstruction of justice, on Dec. 19, 1998. He is found not guilty by the Senate on Feb. 12, 1999. His popularity ratings spike, and he leaves office in 2001 with the highest ratings of any departing president since Gallup began polling at the end of Harry Truman’s term.

Once considered a Republican favorite for Supreme Court justice before the politically unpopular Clinton impeachment, Starr was president of Texas’s Baylor University from 2010 until 2016, when he was forced to step down during. An ongoing lawsuit accuses him and other officials of aiding one student accused of sexual harassment.

Jaworski

The Watergate roadmap helps shape the House investigation that includes damning testimony of events before and after the Watergate break-in. On April 11, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee issued subpoenas for tapes of key White House conversations. Five days later Jaworski issued a subpoena for tapes of 64 additional White House conversations, including the “smoking gun” tape of Nixon ordering that the FBI’s investigation into the Watergate break-in be blocked.

On July 27, 1974, the House committee votes to pursue impeachment. Nixon resigns on Aug. 9, 1974.

The roadmap report won’t be made public until Oct. 31, 2018, after Project Democracy and Lawfare sued for its release.