Should a pregnant person ever go to prison?

Siwatu-Salama Ra knew it was time to go to the hospital. As the early stages of her labor began on a day in late May 2018, officers placed handcuffs on her wrists and led her into the transport van. She arrived to the hospital and to a delivery room where, inside, armed guards would wait all day and night and watch her give birth.

Siwatu-Salama Ra knew it was time to go to the hospital. As the early stages of her labor began on a day in late May 2018, officers placed handcuffs on her wrists and led her into the transport van. She arrived to the hospital and to a delivery room where, inside, armed guards would wait all day and night and watch her give birth.

It was awful, but not as bad as it could be. Many other women in her position are taken to the hospital with handcuffs, chains across their waists, and shackled to the floor of the transport vehicle. Then they are shackled to the bed by their ankles while they give birth. Ra on the other hand was not cuffed in the delivery room.

The doctors and nurses in the maternity ward at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ypsilanti, Michigan, an hour west of Detroit, were used to taking patients from the nearby Huron Valley Correctional Facility, Michigan’s only women’s prison. But Ra’s arrival was a little different; her incarceration a few months earlier was covered by the local news. Hospital staff kept coming into her room to see her, to ask if she needed anything. One nurse said she just wanted to hug her.

There was a trade-off for the lack of restraints, though, she thinks today: increased security once she got to the hospital. Those armed guards—sometimes four, never less than two, always armed and wearing bullet-proof vests—stayed in her delivery room the whole time.

One of the officers in the hospital room was particularly jumpy. She would clutch her gun every time the doctor or nurse walked in, Ra says. “When she heard the door opening, she would jump up and have her hand on her gun,” Ra remembers. “And I’m sitting in my bed, holding my stomach, you know?” What was the officer worried about, she wondered—that she was going to run away while in labor? It was a bigger insult than the handcuffs in the van, to have that woman with that gun in the room. “She was my ultimate punishment,” Ra says.

Ra, now 27, went to prison on March 1, 2018, when she was six-and-a-half months pregnant with her second child. Her first child, Zala, was two, and up until that day the mother-daughter pair were attached at the hip. Before prison, Ra worked as an organizer for a local environmental non-profit in her hometown of Detroit, where she and her mother, Rhonda Anderson, are both well known in the tight-knit activist community. Detroit is a city where families in majority-black neighborhoods are inundated by a constant mist of industrial pollution and where water shutoffs are so frequent the UN has called it a human rights violation; the circumstances have birthed a vibrant environmental activism community with Ra’s family more or less at the center.

Before the day in the delivery room, at 29 weeks pregnant, Ra had a yeast infection so severe that it induced early labor. She had been in prison for three weeks, and that day, March 24, was Zala’s third birthday. Missing it was too much to bear. “I went into a panic attack,” Ra says. “I had an asthma attack, my blood pressure shot up.” Plus an excruciating yeast infection: Thanks to fluctuating hormones, infections are a common nuisance for pregnant women. They are typically treated relatively easily with an over-the-counter cream, but if left untreated, an infection is a birth hazard. Ra says she told the medic in her prison ward about her symptoms, and the medic told her to “splash water” on herself.

Premature birth is extraordinarily dangerous; it’s the number-one cause of infant mortality in the US. There are no good statistics for premature birth in prison, or birth in prison at all, despite the fact that more than 200,000 women are incarcerated in the US. The US government does not regularly count how many pregnant women are in the various state prisons, either, but one 2004 survey from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics found that 4% of women in state prisons were pregnant that year. With a present-day prison population of more than 200,000 women, that would mean—by the most conservative estimate—at least 8,000 women are pregnant in prison at any given time.

In the general population, six infants die per 1,000 live births. But black infants die at birth at a rate more than twice that of white infants. And 24% of incarcerated women are black.

When Ra went into early labor, she was rushed to St. Joseph’s, but not before prison guards conducted a strip search. Frustrated EMTs shouted at the guards that the baby’s heart rate was dropping. During a vaginal exam at the hospital, during which she was shackled to the bed, Ra says her doctor was shocked to find that an infection so severe had gone untreated. The staff managed to use medication to stop her labor and treat the infection, and, after three days in the hospital, Ra went back to the Huron Valley Correctional Facility.

Huron Valley is the only women’s prison in Michigan, and is notoriously overcrowded. Earlier this year, an outbreak of scabies infected as many as 200 women, forcing officials to close the prison to visitors. The state paid a fine in 2018 for forcing guards to work overtime. The Michigan Department of Corrections says the prison’s population of 2,100 is still below the official capacity of 2,400, but a class-action lawsuit filed by incarcerated women’s attorneys in September 2018 noted that storage spaces and other miscellaneous rooms have been turned into cells to fit more prisoners, artificially inflating the capacity. The suit alleged that overcrowding and poor ventilation at the prison amounts to cruel and unusual punishment; a federal judge rejected the suit in October for being too varied in its complaints.

The same month as the class-action case was dismissed, a woman in Ra’s ward nearly bled to death after suffering a miscarriage. She lay for two hours in a pool of her own blood before a doctor was summoned.

Ra was taken back at the hospital nine weeks later, this time at full term. Her delivery physician was a young African American woman. “She wears a natural afro like me. She’s beautiful,” Ra remembers. “I was pushing and pushing and pushing and I said, ‘I’m afraid, I can’t do it no more. I’m afraid.’ And she said, ‘Siwatu, I read all about you, and you are so strong. I know that you’ve been through so much. But you can do this.’ You know? And I said, ‘Okay.’ And she said, ‘So now, give birth to your son.’”

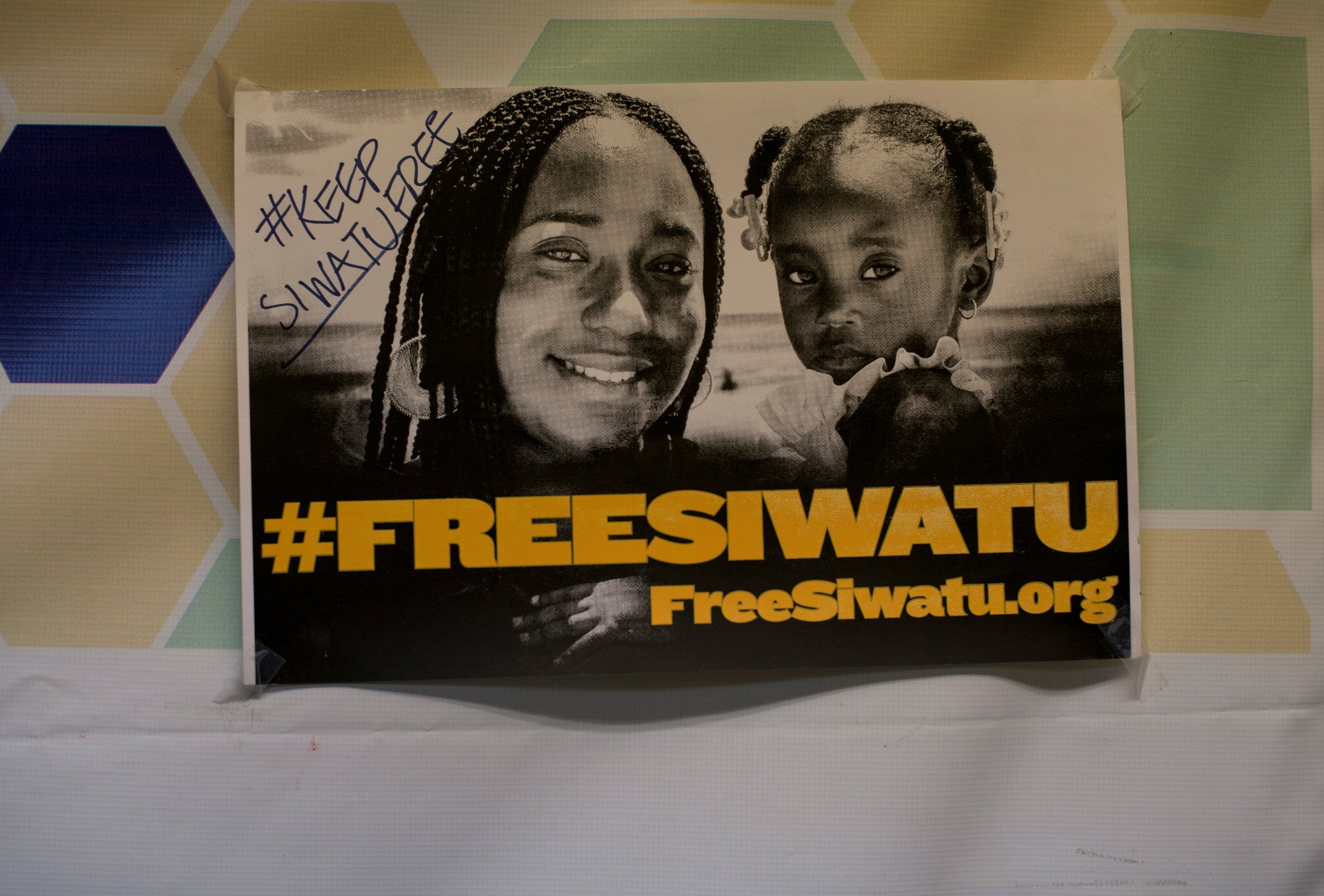

As soon as she was convicted, the Detroit activist community rallied around Ra’s family, developing a sophisticated media campaign, arguing that her incarceration was unjust. Her case made the news, and ballooned into a symbol of everything wrong with the justice system. The activists called themselves the “Free Siwatu” team, and made a website, held press conferences, and met once a week to develop a strategy to get her out. As many as 20 people would pack into Anderson’s house, bringing trays of food and their babies. The case had broad appeal; Ra went to prison, the activists said, for defending herself with a gun she was licensed to carry—it was, in a way, a gun-rights issue. She was also a young black woman acting in self defense—using non-deadly force, for that matter, given that the gun was unloaded—whose fear in the moment could not be comprehended by the judicial system. So it was a social justice issue too. Local news and then a smattering of national outlets picked the story up.

Prisons don’t typically notify families when an incarcerated relative is giving birth, and none are allowed to be present, but someone called Ra’s mother that day to let her know that her daughter was in labor. Rhonda Anderson won’t say who made the call because it certainly wasn’t allowed. She drove the hour from her Detroit home to St. Joseph’s, parked her car in the lot, cut her engine, and sat there. She knew she couldn’t go in. “I just wanted her to feel me there.”

Pregnancy and birth are the only routine functions of the human body that can kill a person. Everything from poor diet to air pollution can harm a developing fetus. For the mother, so much can go wrong, and stresses that a human body could usually handle—like a spike in blood pressure—can be dangerous and even fatal while the body’s resources are devoted to carrying a child to term.

Pregnancy is a particular hazard in the US, where mothers die immediately before, during, or after labor more often than in any other developed country. For every 100,000 babies born in the US, 17 mothers die. The next-worse rate among developed countries is in the UK, where nine women die per 100,000 live births.

That ratio is worse still for black women in the US, who are three to four times as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes—either during birth, or directly before or after—compared to white women in the country, according to the US Centers for Disease Control.

How prison fits into that matrix of risk is not well-studied, but we can state the obvious: Prison, at the very least, is stressful. And emotional stress during pregnancy is associated with every negative pregnancy outcome imaginable, including premature birth, lower birth weight, and impaired neurological development—each of which separately increase the likelihood of an infant dying.

That clear risk raises a complicated legal question: should any pregnant person go to prison?

The Eighth Amendment to the US Constitution makes “cruel and unusual punishment” illegal. Informally, the standard for whether something is truly an Eighth Amendment issue is whether or not it “shocks the conscience,” says Corene Kendrick, a staff attorney at the Prison Law Office, a California-based non-profit that has brought a number of constitutional suits against state prison systems. Incarcerating a pregnant woman just doesn’t do that, at least not within the US legal landscape, and so no one has been able to argue that pregnancy alone is enough to make an Eighth Amendment case.

A medical case, however, might be stronger. Right now, much of the debate around incarceration in the US is focused on immigrants detained at the country’s border with Mexico. Physicians have been among the professional groups most vocally opposed to the current policies. “I think every effort must be made to prevent pregnant women from going to detention,” says Alan Shapiro, a pediatrician and co-founder of Terra Firma, an organization that provides medical and legal services to undocumented children. “Prison or detention itself is a trauma. It’s not a therapeutic environment, it’s an environment that creates more stress.” The unavoidable hardship of being a prisoner threatens the health of mother and fetus, says Shapiro. And then comes the ultimate punishment: child separation. In most cases in the US, an infant is taken from its incarcerated mother within 24 to 48 hours after giving birth, and given to either a family member or to the foster system, if there is no family member willing to take the child or if the state decides the willing family member is “unfit” to care for them.

The research is clear on this point: The damage of separation, psychologically, amounts to trauma. Trauma during childhood in general is estimated to be associated with roughly 30% of all psychological disorders experienced as an adult. But the trauma of separation is particularly insidious.

Charles Nelson, a pediatrics professor at Harvard Medical School, studied children in Romanian orphanages who were separated from their parents in the first two years of their life. He found that by the time they were eight years old, the parts of their brain responsible for cognitive performance, emotion, attention, and sensory processing had grown less than those of their counterparts in local families. They scored lower on IQ tests. They were at markedly higher risk of an ADHD diagnosis. They appeared not to have a normal response to stress—they seemed numb in situations that should have induced their flight-or-fight response. “If you think of the brain as a lightbulb,” Nelson told the Washington Post in June 2018, “it’s as though there was a dimmer that had reduced them from a 100-watt bulb to 30 watts.”

Meanwhile, in 2006, the Australian government found that Aboriginal children separated from their parents—a national policy that lasted well into the 1960s—were almost twice as likely to be arrested as adults, more than twice as likely to have a gambling addiction or live with someone who does, and about 60% more likely to abuse alcohol or live with someone who does.

For those who give birth in the US prison system, all but a handful lucky enough to get into one of the few residential prison nursery programs in the country will have their infants removed within a day or two.

Women are the fastest-growing demographic of the US prison population. The number of incarcerated women in the US rose by nearly 400% in the last three decades (a rate over twice as high as the rate for men), from about 42,000 women in 1985 to about 210,000 in 2015.

And roughly 60% of them are mothers to children under 18. (About half of men in prison are fathers.)

Newborns aren’t the only children exposed to separation trauma. In total, 1.7 million children in the US faced separation from their parents due to prison sentences as of 2007, the last date for which the US Bureau of Justice Statistics has published an estimate (pdf). Roughly a quarter of those children are under four years old, and more than half are under nine.

That year, more than 2% (pdf) of all children in the US had a parent in prison. A Hispanic child was more than two and a half times more likely than a white child to have a parent in prison, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Black children, meanwhile, were seven and a half times more likely. Put another way, one in 15 black children had a parent in prison.

The lack of a parent, especially in a child’s earliest years, may also mean a lack of an emotional buffer between a child and any hardship they experience in the world, and diminished ability to respond normally to stress. The longer the parent is absent, the worse the toll. “At some point, if the exposure to stress is chronic, and the buffer is not there, then the child’s physiology is always at this level of stress. Then we call that ‘toxic stress,’” Shapiro, the pediatrician, says. “It can lead to psychological and physical problems… [like] diabetes, high blood pressure, possibly even cancer.”

But before the separation comes months of pregnancy, and then birth, which “are normal physiological occurrences but are definitely fraught with potential dangers,” Shapiro says. For prison to not pose an additional medical threat to that process, “close monitoring must occur in exactly the same way in a detention center that it would be in a community,” he says. But it often doesn’t. US prisons are required to offer women prenatal care, but there are no federal standards, so what exactly is offered, and how, varies depending on location. In 2004, the last year for which data are available, just 54% of pregnant women in US prisons got some kind of prenatal care, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Postnatal care can be just as critical.

In Arizona in 2013, a young incarcerated woman named Regan Clarine gave birth by C-section. Back at the state prison, her incision kept opening up. The prison medics tore open packets of table sugar and poured them into the wound. “Apparently what the medical staff told her was that it’s a way of keeping wounds clean,” says Kendrick, the attorney at the Prison Law Office, which uncovered the story while interviewing prisoners during the course of a lawsuit filed against the Arizona correctional system for inadequate medical care. “It’s bananas.” Sugar was used to dress wounds until the invention of antibiotics in the early 1900s, because it can dehydrate bacterial cells. But it no longer has a place in modern medicine.

Arizona settled the class-action suit in 2014, but in 2018, a judge ordered the state to pay $1.4 million in fines for failing to meaningfully improve its prison medical system.

Chanell Harvey was parked outside Ra’s mother’s house and wouldn’t leave.

It was around 8pm on July 17, 2017 in central Detroit. Sunset was at least an hour away. Ra and her mother, Rhonda Anderson, sat on the porch; Ra’s 2-year-old daughter Zala was inside the family’s parked car a few feet away, playing with the steering wheel (the engine was off). Ra’s 14-year-old niece was inside the house. According to Ra, Harvey was furious. Harvey’s teenage daughter was supposed to spend the night at Anderson’s house while Harvey went to work. But her daughter had beat up Ra’s niece at school and Ra’s mother didn’t want her there. That meant the woman couldn’t go to work. And now she was screaming at the two women.

Harvey backed her car up, put it in drive and accelerated, bumping her car into Ra’s, where Zala was still playing. Ra reacted immediately. She ran off the porch, opened the passenger side door of her car, and grabbed Zala out of it, handing the toddler off to her niece, who had at this point come out of the house.

Ra says she saw Harvey put her car into drive again, and thought the woman was going to run right into her mother, who had walked over towards the driveway.

So Ra reached into her glove compartment, and pulled out her gun.

She’d only begun carrying a firearm a year earlier, after an incident when she’d been driving with Zala and another car swerved around traffic, pulling up behind her. The driver—male, white, middle-aged—honked; Ra thinks maybe he thought she was driving too slowly. After a moment, the driver pulled up beside her and, she says, pointed a gun at her through the window, screamed expletives, then drove off. Shaken, she took down his license plate and went to the police, who looked the numbers up. They told her there was no firearm license on the profile of the car’s owner—maybe she had made a mistake.

Carrying a gun of her own suddenly seemed a good idea. Her husband, Kamal Ali Muhammad, who was already licensed to carry a firearm, agreed. Plus, the horror of five years earlier was still on both their minds.

One night in 2012, Ra was supposed to have dinner with two friends from high school. Abreeya Brown and Ashley Conaway were due to testify soon as witnesses in an attempted murder case and were feeling anxious. That night, something came up, and Ra couldn’t meet them as planned.

When she tried to get in touch with them later, they didn’t pick up their phones. Days stretched into weeks. Their bodies turned up three weeks later; they had been bound and shot in the head. Brown was 18 and Conaway was 22. Five men were charged with their murder, including the man they were set to testify against.

Ra was almost there that night. So, yeah, Muhammad wanted her to have a gun.

Later, in court, Harvey would say she hit Ra’s car by accident; she was just trying to turn her car around to leave. Witnesses disputed that claim. In any case, in that moment, Ra thought Harvey had absolutely lost it.

So Ra opened the glove compartment, pulled out her unloaded gun, pointed it at Harvey, and told her to go home. It was the first time she’d ever pointed it at someone.

Harvey held up her cellphone and took a photo of Ra. Then she drove straight to the police department.

That’s when the nightmare began.

The trial began on Jan. 30, 2018 and lasted about a week. On February 8, the jury came back with a verdict: guilty. The mandatory minimum sentence for a firearm felony in Michigan is two years. Later that day, Ra drove to Zala’s preschool to let them know what was going on. The director of the school promised her Zala would get “extra love” in the classroom starting then. “She held me and we both cried,” Ra says.

At the time, Ra was nearly six months pregnant with her second child.

On March 1, when Ra and her family returned for sentencing, she was under the impression that, whatever the result, she’d have time left at home before her imprisonment. Her lawyer would ask for a delay until she had her baby; she was a six-and-a-half month pregnant woman with no prior record, and expected the delay request would be granted. The courtroom was packed with Detroit activists in a show of support for a family that had championed Detroit causes forever.

But judge Thomas Hathaway denied those requests and gave her the two years, starting right then. Police stood up to take her away. She started screaming.

Anderson, her mother, was in the courtroom. To her, everything felt like it was happening in slow motion. All she wanted to do was run towards her daughter, but Anderson was trapped in a row of seats. She wondered frantically if she should jump over them. But she didn’t, and then it was over; Ra was walked out of the courtroom. Outside, the long Michigan winter had blanketed the day in white. It was beautiful, Anderson remembers. It felt surreal.

On May 21, 2018, Ra gave birth to Zakai, a healthy baby boy, in St. Joseph’s Hospital.

Ra and Muhammad are Muslim, and when a Muslim baby is born, a family member—typically the father, but if no male family is present, the mother—sings the azaan, the Muslim call to prayer, into the baby’s ear, surrounded by family. The well-meaning staff at St. Joseph’s knew Ra was Muslim, and someone ran around the maternity floor looking for Muslim women who might want to attend, Ra recalls. A group of people crowded in the room, and the non-Muslim among them looked like they were “expecting this big thing,” Ra says. But it was a quiet ceremony. Ra whisper-sang the prayer into Zakai’s ear.

After the birth, Ra had two-and-half days in the hospital to recover before she was sent back to prison. She held Zakai the whole time. “I did not take a lick of sleep. I didn’t even want to take my eyes off that boy,” she remembers. “Not even a minute. I stayed up for three days. Because I wanted to spend every moment with him, knowing that I would have to leave him.”

Guards drove Ra back to prison. After that, a prison official called Muhammad to come pick up Zakai and bring him home.

We’ve embedded audio clips of phone conversations we had with Ra from prison during the reporting of this story.

Back at prison, Ra became depressed. Her breasts were swollen and leaking milk. The corrections department in Michigan, as in most states, does not have pumping equipment available for prisoners. Ra saw her leaking milk as a physical manifestation of her aching heart. “Literally your body is seeking your baby. Just as much as that baby is seeking its mom, your body, your mind, is also seeking that baby,” Ra says. She couldn’t stop thinking about him, and didn’t want to. Her mind was reeling. Was she still a mother if she wasn’t with her baby?

But depression in prison is a tricky thing. Ra worried that if she was too distraught, openly sobbing, say, or hyperventilating from grief, she could be sent to solitary confinement. “They don’t want you to cry,” says Ra. So she worked on bottling her feelings.

She lived in a ward of the prison reserved for pregnant and postpartum women, and watched other women come back from a day or two in the hospital without their baby, their faces swollen from crying. “Childbirth is something that is so grand in a woman’s life,” Ra says. But not here it wasn’t, not like this. “No woman expects to be pregnant in prison. No woman plans on that.”

She watched another cellmate come back from having a C-section, her stomach still healing from the stitches and no baby to show for it. She’d been transported back to the prison with a chain around her belly, right over the fresh wound. Like all returning mothers, she was expected to rejoin the daily routines of the prison, as though nothing was wrong. No time to grieve. “This woman came back and she said, ‘Ra, It’s so wrong how they do it.’ And all I could say was, ‘I know, I do know, I know all about it. And I’m so sorry you had to go through that,’” Ra says.

Incarcerated women giving birth go through “the unimaginable,” as Ra calls it; a crucible with no witness, and no apt words to describe it. Then they’re sent back to prison with as much ceremony as if they’d passed a kidney stone.

Relative to many of the other women who give birth in prison, Ra was lucky: Zakai went home to a father and a big, supportive family. Ra could call home every day, and hear how Zakai was doing. She felt helpless, but at least sort of involved, since she could keep up with the daily minutiae of the family’s life over the phone. But in other cases, incarcerated women who give birth in the US prison system are forced to hand over their infants to the foster system, and, according to US federal law, a parent whose child has spent 15 out of the most recent 22 months in foster care can lose their parental rights permanently.

Several countries have decided that the lasting damage to the child—who is ostensibly not the object of a state’s penal system—is sufficient reason not to separate them from their mother; that the resulting trauma so intolerable as to be avoided altogether. According a 2014 report assembled by the US Law Library of Congress, 97 other countries and regions have rules on the books preventing immediate separation.

For example, Argentinian law allows any incarcerated mother to keep her children with her in prison until they are four years old, and requires prisons to provide special child-care facilities (though the report notes only one prison actually had those accommodations as of 2011). In Spain, Singapore, Switzerland, Taiwan, and Venezuela, children can live with their mothers in prison until they are three. In Qatar, Oman, Yemen, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, the cutoff age is two. In Turkey, it’s six. In South Korea, mothers can apply for permission from their prison warden to raise their infant in prison until the child is 18 months old. In some parts of the world, like Zimbabwe, Haiti, Botswana, Malawi, Tuvalu and Swaziland, the cutoff isn’t based on age, but rather whenever the child is weaned from breastfeeding. In other countries, the law is more expansive and vague; in Luxembourg, for example, a child can stay as long as they are “too young be separated from their mother.”

Sweden changed its law in 2011 to be gender neutral, allowing a child to stay in prison with their mother or father, so long as the parent’s sentence is short and social services has determined it is in the best interest of the child. In Denmark, prisoners who were in a relationship before their conviction can live together in prison, resulting in some mothers and fathers raising their child in prison together.

Despite having the world’s highest incarceration rate, US has no law on the books governing—or preventing—child separation in prison, but in a few discrete cases, states are setting their own rules. Right now, 11 states have prison nurseries, where women can enroll in a program allowing them to raise their babies while they serve their terms. The research on these programs is promising; one five-year study looked at a nursery program in New York, and found that the babies raised there developed the same degree of secure attachment characteristics as their peers raised in families who hadn’t encountered the justice system at all. Other research found the recidivism rate at one New York prison was halved for the women who participated in the program compared to those who didn’t.

At Decatur Correctional Center, Illinois’ state women’s prison, has one such program. To qualify, the women must have been incarcerated for nonviolent crimes and in most cases have sentences of two years or less. They live in a separate wing of the prison where bar-less cells are outfitted with cribs and changing tables, according to the Washington Post. Murals line the walls, and other inmates serve as daycare workers while the mothers take GED classes or get counseling for drug or alcohol abuse.

In general in the US, once you go to prison, odds are more likely than not that you’ll be back. More than 60% of formerly incarcerated people are arrested within three years of their release as of 2018. But among the 90 women who have gone through the Illinois program over the last 11 years, only two (or about 2.2%) have returned to prison in the following three years. It’s a small sample, but that’s a shockingly low recidivism rate.

Once Ra had been away for a few months, Muhammad started to notice changes in Zala. She got quieter, more serious. Less goofy. “More grown up,” he says. From the start, they’d go twice a week to Huron Valley to visit Ra, where body searches extend even to infants, and Muhammad was forced to hand off Zakai to a prison guard who would replace the baby’s diaper with a prison-issued one. “We’ve had far too many instances where a prisoner will hide drugs in the diaper. We put our own diaper on the baby,” explains Chris Gautz, a spokesman for the Michigan Department of Corrections.

After a while, little Zala started to take her shoes and socks off for the body search before the guard even asked. She started to repeat the words the guard said, having memorized them: “Open door one, close door two.”

She wasn’t allowed to sit in her mother’s lap in the crowded visiting room. That was only permitted for children under two, according to prison rules, and Zala was three now.

Ra comes from a family of braiders. Mothers did their babies’ hair; it was an act of love as much as a routine of parenting. So on visiting days, Ra broke a plastic fork, drew her daughter near her, and used it to comb out the child’s hair. That also wasn’t allowed, but the guards would just give her a look and let it go.

Breastfeeding isn’t allowed either. One time she put Zakai into her shirt anyway. The family leaned in around the table, to block the guards’ view.

Sometimes Zakai would scream when Ra tried to hold him. After one visit, Ra called her mother and broke down. It was too much, Ra said, to see Zakai act like he didn’t know her. Anderson told her daughter, “no, tootsie, it was just that room”—those fluorescent lights, the constant noise of other families and other babies crying—it was too harsh an environment for an infant to stand.

After exactly 15 minutes, a disembodied voice broke through the call. “THANK YOU FOR USING GTL.” And then they heard a low beep, and the call cut off. That’s how it went: Anderson would talk to her daughter in 15 minute snatches before the voice came back and the call dropped. (GTL is Global Tel Link, a private company used by many prisons for phone services.)

This time, Anderson put her phone down on her dining room table. She’d kept her tone level and reassuring a moment before, but now took a slow breath. “I’m trying to keep her above water but I’m drowning,” Anderson said. “We are living a nightmare that we can’t wake up from. And it’s destroying Siwatu.”

The next day, Muhammad brought Zala to play in a small park in downtown Detroit. She climbed around a fountain while Muhammad lifted Zakai out of his stroller, held him in the crook of his arm, and fed him a bottle. Zakai, four months old, was all baby rolls and bright eyes, with a full head of hair. He looked around, curious, and seemed content, never making a sound. An older couple stopped to and smiled at the baby. “You have beautiful children,” they said, and Muhammad nodded. “God gave me good kids. It’s like they came equipped with so much. They’re so mild-mannered,” he said.

As we sat in the park, Muhammad’s cell phone rang. It was Ra. She asked to speak to Zala.

Zala held the phone in front of her and made silly faces. “Mama, look,” she said a few times, sticking her tongue out at the screen, not understanding that her mother couldn’t see her face.

Calls like this cost $0.16 a minute, which is $10 an hour. Muhammad sends Ra money for the commissary, which she can use to buy food and toiletries. “The tampons they give you are horrible. And there’s no pads with wings,” he says. “You can send up to $300 every two weeks, and you can send $80 for a box with toilet paper, toothbrush, deodorant.”

He’s worried about what she’s eating. The food, he says, is horrible. “Yesterday she said it was the second day in a row they found maggots in it—in the corn or something.”

On Nov. 14, 2018, after 258 days in prison, Siwatu walked out of Huron Valley to a small crowd. She hugged her lawyer, Wade Fink, then her mother, then her babies and husband.

Fink had filed a motion for release several weeks earlier. Similar motions in the past had been rejected; this time, the courts allowed Ra to be released on bond, pending an appeal of her case. She could be sent back to prison whenever the appellate court gets around to her case in a few months or a year—or she could have the felony cleared. This all amounts to a tremendous victory; successful appeals are “very rare,” Fink says.

Ra has been home for almost five months. She wears a GPS tracker on her ankle now, and has a curfew of 7pm.

Zala often eyes her mother’s ankle bracelet. “Even though she’s three, this little girl, her soul has to be over 100,” Ra says. Zala won’t sleep without her, and when they’re at home, she checks on Ra’s location constantly, tracking her movements from room to room. “She has to stay very close to me. She has to know where I am inside the house all the time,” Ra says. “In her sleep she holds my hand. She can’t go to sleep without some body part touching me to make sure I’m still there.”

Ra and Zala recently started seeing a psychologist, to “to help us navigate through what has happened,” she says.

But she’s out. She’s with her babies. And she can’t stop thinking about the women who aren’t.

The day Ra walked out of Huron Valley, there were eight pregnant women in her ward. In total, 38 babies were born to women at Huron Valley in 2018, including one set of twins. Four women had miscarriages.

On Feb. 19, 2019, after months of negotiations, the Michigan Prison Doula Initiative and the Michigan Department of Corrections signed a memorandum of understanding to launch a doula program at Huron Valley. From now on, every pregnant woman brought to the prison will have the option of working with a doula leading up to their birth; the doula will later be with them in the delivery room and can coach them through the trial of giving up their child. The Michigan Department of Corrections joins a very few other prison systems in the US that allow doulas.

The Michigan corrections department is also revising some of its policies around pregnant women, including its shackling rules; “We are updating it to say that only soft restraints should be used with pregnant prisoners,” says Chris Gautz, the department spokesman, and that handcuffs are the only restraints that can be used while they’re in transit.

The prison says it plans to begin allowing mothers and their newborns to spend an hour with the family member who will take the baby in the hospital; in the past and even today, the family member is only called to pick the infant up after the mother has been transported back to prison. “We’re trying to transform this prison, to make sure it is a gender-responsive, trauma-informed facility in all things that we do,” Gautz says.

National attempts to improve the lives of incarcerated women have had uneven results. For example, in 2018, Congress passed a bill to prevent the shackling of federally incarcerated women during pregnancy and through postpartum recovery. But policies in state prisons remains piecemeal; as of this year, 19 states ban the practice, 25 states restrict shackling in some way, and six states have no policy on the books about the practice at all. And federal prisons only account for some 10% of incarcerated women in the US.

Amid the vast sea of hazards a pregnant woman or new mother may face in prison, shackling is only one lagoon, just one more way to drown.

Maybe most of the country simply doesn’t know what happens when a pregnant woman goes to prison. “I consider myself up and aware of things. I never knew this,” Anderson says. “We think we know, but we didn’t know what was going on inside of these places.”

Now that she knows, she can’t get the image of shackled pregnant women out of her head. “You wouldn’t do that to a dog,” she says. “You know this country would have a fit if a picture came out of a dog shackled like that.”