Welcome to the world’s biggest tax haven: The United States of America

Late one fall night in 2008, Christine Nelson was dropped outside a Houston strip mall by the man who had been trafficking her for a year and a half.

Late one fall night in 2008, Christine Nelson was dropped outside a Houston strip mall by the man who had been trafficking her for a year and a half.

A man met Christine and another victim of the same trafficker and told them to get into the back of a truck. About 45 minutes later, Christine got out onto a dirt road, outside what looked in the dark like another strip mall. She was led into a building, which had signs outside advertising a massage parlor.

Upstairs, the madam who ran the parlor assigned her a windowless room at the end of a dingy corridor. “There was a massage bed in there, there was low light in there. You couldn’t really see the conditions of it,” she says. “It was dirty, it was not a clean place. You could actually smell the food from the hot plate that was down the other end of the hall.”

Christine’s job was to give “happy endings” to the clients. Another woman from the parlor sat in on her first session to ensure she was doing her job properly. “It was just non-stop,” she says. “There were tons and tons of men.” The madam initially refused to let her leave, only giving her the parlor’s address after 24 hours.

Christine eventually managed to leave her trafficker and is now a fellow with Survivor Alliance, an NGO that helps trafficking survivors, but what she recounts is a brush with a $2.5 billion industry—the illegal massage business. Most victims of the industry are trafficked from East Asia, often heavily indebted to their traffickers, and forced to live in the parlors, terrified that if they leave they’ll be arrested and deported.

The criminals at the top of these trafficking chains operate with a degree of impunity thanks to what may seem an arcane device—US incorporation law. Unlike most traffickers, these businesses operate partially in the open, advertising their wares and many of them registering as legitimate companies. But when you try to find the perpetrators, if they have registered at all, they’ll have done so as anonymous shell companies, with a front person listed as a company officer or the owner. That person will often have no idea who’s behind the business.

Rochelle Keyhan is a former sex-crimes prosecutor and now CEO of Collective Liberty, a non-profit fighting human trafficking. As a prosecutor in Philadelphia in 2016, she narrowed in on what she called “two blocks of the most hyper-secure illegal massage businesses in the whole country.” There were online reviews of the parlors going back to the 1980s, but all she could find was that one of them had been sold from one shell company to another for $1. This seemed implausible—the real estate alone was probably worth up to $1 million, she said.

“That was a dead end, because shell companies—there’s no visibility into them. I did everything I could to search on the shell companies but no identifiable person was attached to them,” Keyhan says.

A growth industry fueled by lies

The corporate secrecy beloved of human traffickers touches almost every facet of American life. It enables drug trafficking, terrorist financing, money laundering, political dark money, and, of course, old-fashioned tax evasion. It’s an enormous industry; the Treasury reported last year that domestic crime produces $300 billion for potential laundering every year—not including tax evasion—and that criminals make rampant use of shell companies.

The incorporation and trust industries have so exploded in recent years that the Tax Justice Network (TJN), a research and advocacy group, ranks the US the second worst tax haven in the world—behind only Switzerland. It’s not just activists who think so: In 2015, Andrew Penney, a managing director at European banking giant Rothschild, wrote in a draft presentation that the US “is effectively the biggest tax haven in the world,” according to a 2016 Bloomberg article, which reported that wealthy families are pulling their money in droves out of Switzerland and the Cayman Islands, redirecting it to trusts in states like Nevada and South Dakota. US authorities have “little appetite” to enforce the tax laws of the countries this cash first came from, Penney’s draft continued. (He says he cut both phrases before giving the presentation.)

Criminals flock to the world’s biggest economy, seeking out its stability, deep corporate anonymity, and strong courts that prevent their assets being taken without rigorous due process. The US, in turn, seems to welcome them with open arms. In a groundbreaking 2012 study, three academics sent sting emails to thousands of firms around the world whose business is creating shell companies, and asked them to set up a firm. The emails gave hints, variously, that the companies might be for kleptocrats, terrorists, or tax evaders. They found it’s easier to form an untraceable shell firm in the US than anywhere except Kenya; just 0.6% of US company providers met international standards.

It’s “embarrassing,” US senator Sheldon Whitehouse, a former prosecutor from Rhode Island, told me in 2017. He called his country a “laggard…in the gutter with the criminals and the kleptocrats.”

The embarrassment peaked in 2016, when president Obama was openly taunted by Allan Bell, chief minister of the tiny Isle of Man, a UK-linked tax haven. Obama had spent years trying to get the world’s tax havens to reform, saying on the 2008 campaign trail, “You’ve got a building in the Cayman Islands that supposedly houses 12,000 corporations. That’s either the biggest building or the biggest tax scam on record.”

Eight years later, Bell retorted: “There is one building in Delaware which has 285,000 companies registered in that one building and they don’t know the beneficial owners of any of them,” Bell said. “That’s 10 times the total number of companies we have in the Isle of Man and we know the beneficial owners of all of them.”

Delaware is the most famous of America’s internal tax havens, with nearly 1.4 million businesses and two-thirds of the Fortune 500 registered there. It’s also no stranger to criminals. Delaware LLC owners have included Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout (known as the “merchant of death”), jailed former Trump campaign chair Paul Manafort, and the owners of child sex trafficking hotbed Backpage.com.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, America’s second smallest state showed up as the second-least compliant with international standards in the above study. The only state ranked worse was Nevada, which has branded itself the “Delaware of the West.”

All this opacity has worldwide knock-on effects, says Alex Cobham, CEO of TJN. “The United States’ role is not only in the secrecy it provides but in the norms that it sets,” he says, arguing that competition between US states with opaque laws gives cover to money-laundering havens like the British Virgin Islands, which ignore pressure from Europe and keep providing anonymity to global criminals.

The US has also refused to sign up to information-sharing agreements with other countries aimed at stopping tax evasion. It only gives that info to allies. Sometimes there are good reasons for not sharing such data with nasty regimes, but it also stops poor countries from gaining crucial knowledge about the money being stolen from their economies.

“It’s probably fair to say that the US is already the biggest global jurisdiction in promoting corruption and tax abuse all over the world,” Cobham says.

To find out how the world’s top cop fell down this path, I went on a journey around Tax Haven USA, starting with the state that first created America’s first Limited Liability Company laws: the vast, empty plains of Wyoming.

Wyoming: The Cowboy State where bandits set up shop

Wyoming is an unlikely business center. It’s around the same physical size as my native UK, but has less than 1% of the population—around 580,000 people.

Few people walk the streets of its capital, Cheyenne. Those who do are met by a biting wind that whips off the prairie, taking no heed of the town’s sparse, beige buildings, which are punctuated by the occasional relic of the Old West. The city’s airport spent most of 2018 empty after its sole carrier shut up shop. If you want to fly to Cheyenne now, your only option is a tiny plane from Dallas at 9:30am.

It’s all quite charmingly parochial—and the state faces a rather parochial problem: a $216 million budget deficit. In California, one of the world’s largest economies, that would be pocket change. But in Wyoming, it’s around 6% of the state’s $3.5 billion two-year budget. In trying to fill that hole, the 90-person part-time legislature has made the LLC industry one of its main targets.

The state passed America’s first LLC law in 1977, and it now has almost one company for every three people. The original legislation was reportedly written by an oil firm from Colorado, which had been working in Latin America and apparently rather liked the Panamanian structures known as limitadas. The law effectively merged the best aspects of two different types of companies, taking the liability protections of corporations and blending them with the tax benefits of a partnership. Hamilton Brothers Oil Company reportedly first targeted Alaska as home for the law, but, having failed there, turned to another sparsely populated, oil-rich state, and persuaded Wyoming’s legislators to adopt it.

There are plenty of legitimate reasons to want to use an LLC. The example perhaps most frequently rolled out is that of a doctor, sued for an honest mistake during surgery. If her clinic is an LLC, she can only lose assets held by the clinic—her patients can’t take her house and savings. The same goes for a debt-laden entrepreneur whose product fails, meaning the bank can’t come after their personal assets.

At first, LLCs made barely a ripple. A decade after Wyoming passed its bill, less than 100 companies had reportedly registered as LLCs. In 1988, that changed. The IRS finally recognized their legality, meaning, depending on their attributes, companies could be sure that as LLCs they’d have both tax benefits and limited liability. Then came the deluge: by 1996, every state had reportedly passed LLC laws. The number of them boomed, hitting nearly 600,000 by the turn of the millennium, with a net income (minus deficit) of $34.7 billion. By 2015, there were 2.5 million LLCs in the US, earning $248 billion, according to IRS data.

The vast majority of these are entirely legitimate businesses. However, LLCs attract less-wholesome characters via a different attribute: potentially total anonymity for the owners. A criminal setting up a business can easily avoid having their name on its paperwork. One journalist demonstrated this ease by setting up Delaware company called She Sells Seashells LLC for her cat. She visited an elderly couple whose job is to act as “registered agents,” taking a small fee to set up a company and do its paperwork from time-to-time. The process took 5 minutes, and the registered agents didn’t check any ID to see whether she was giving a real name and address.

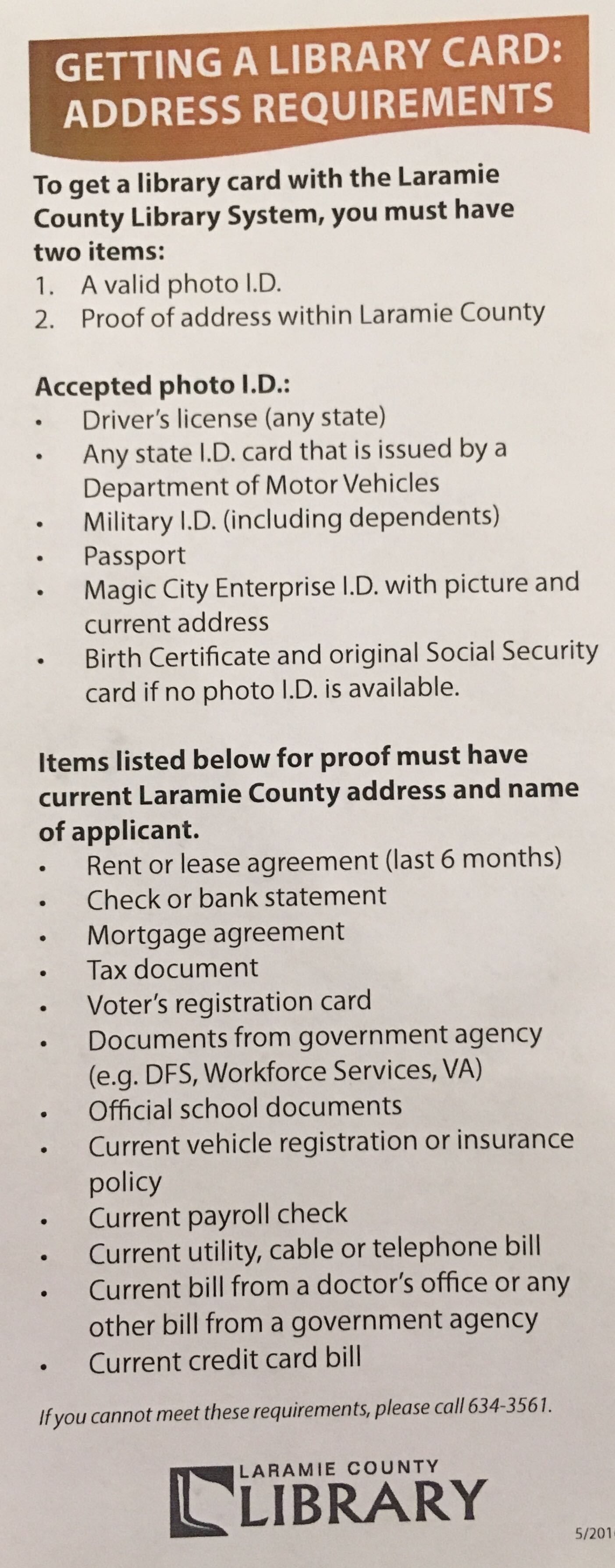

In search of some perspective, I tried to get a library card while in Wyoming. The guy working there apologetically told me that I needed proof of address in the local county plus government-issued photo ID. He handed over a rigorous list of documents that qualified. Wyoming is not alone here—Global Financial Integrity found this year that every US state had more stringent demands for getting a library card than setting up a company.

To keep their name off company documents, smart criminals tend to register someone else as the company’s designated officer to receive any questions from authorities. That person will often either know nothing about the company and its ownership, or be the lawyer for the actual owner. Having a lawyer fill that role can give you the extra shield of attorney-client privilege. Then, if you’re being thorough about things, you’ll probably create another anonymous shell company in another state to hold your original shell. Then another one, perhaps in a foreign tax haven like the Cayman Islands. And so on. Then, if you hear law enforcement are looking into one of the shells down the chain, you transfer your assets somewhere else. By the time the feds have got through that web, you’ve sailed away on your super-yacht.

There’s at least one above-board reason for wanting that anonymity. The oft-cited example is Disney buying the land in Florida that became Disney World by using anonymous shell companies and the company’s lawyer obscuring his identity. If they had approached the owners as Disney, they’d have seen a steep hike in prices. This was legal, though some argue it gave them an unfair advantage in negotiations.

Beyond that case, it’s hard to find other good business reasons for such secrecy. Tara Nethercott, a sharp and charismatic Wyoming state senator, spent a long time in her law firm’s shiny board room telling me that anonymity creates “efficient” and “effective” business conditions. However, she came up short when I pressed her on how transparency actually makes business less efficient. “I don’t know,” she eventually acknowledged. “As a lawmaker, I’d encourage you to ask industry. Why is it that business wants anonymity in corporate structures?”

So, I asked the US Chamber of Commerce, a staunch lobbyist against corporate transparency bills in Congress. Their press office didn’t reply to four requests for comment.

After my failed library visit, I went in search a business whose clients have had a number of scraps with the media and the courts: Wyoming Corporate Services Inc. I found it on the ground floor of a nondescript two-story building, which shared a wall with the city’s main police station.

While there’s no indication that the company or its owner Gerald Pitts have ever done anything illegal, a 2011 Reuters investigation revealed it set up firms for some unsavory figures. These include a former Ukrainian prime minister once jailed for money laundering; a man who had been banned from government contracting for flogging counterfeit truck parts to the Pentagon; and another man who allegedly helped poker operators evade a ban on internet gambling. Back then, Wyoming Corporate Services advertised its services as such:

“A corporation is a legal person created by state statute that can be used as a fall guy, a servant, a good friend or a decoy,” the company’s website said, according to Reuters. “A person you control… yet cannot be held accountable for its actions. Imagine the possibilities!”

Its website is now somewhat subtler, but still carries touches of innuendo, noting that “Wyoming draws little attention” in a list of reasons to incorporate there.

My own reporting suggests that, since that Reuters report, Pitts, whether intentionally or not, has continued to work with clients who have run into legal trouble. Searching through legal filings, I found a 2013 FTC complaint alleged that three men based in Montreal used shell companies—some of which were set up by Pitts’s firm—in an operation that “bilked more than $14 million from small businesses and churches in the United States.” An Illinois court halted the men’s scheme and ordered them to repay $15.6 million to the victims, via the FTC. Pitts was not cited in the complaint.

In another case, Houston CEO Ray Charles Davis, whom the SEC and New York prosecutors allege was involved in two fraudulent schemes involving a total $58 million, allegedly spent $4.2 million via a shell company registered at Pitts’ address. (Pitts and his firm don’t appear on the filing paperwork, however.) Davis, who denied the charges, died during the case, which was dismissed due to his passing.

What did Mr Pitts have to say about all this? Very little, it seems. I made four phone calls and two in-person visits to his office, but each time I was told he was out. He doesn’t seem too enamored of the press: When CNBC republished the Reuters article in 2014, Pitts tried to sue both publications, arguing that the piece was defamatory, since some information—such as his address—was now out of date. The suit was thrown out.

Eventually, Pitts replied to an emailed request for comment, saying, “a small fraction” of his clients were alleged to have done illegal things. “We do not knowingly provide help to those sorts of people,” he wrote. “It is like Home Depot selling a hammer that is used in an unlawful manner, there is no way that they could know that person was going to do that.”

Most noteworthy, however, is the allegation that the firm created a so-called “shelf company” for Pavlo Lazarenko, the former Ukrainian prime minister once ranked the eighth-most corrupt official in the world by Transparency International. A “shelf company” is an empty firm set up years in advance so it can be bought off the shelf and seem like an established business to anyone who interacts with it. Lazarenko is accused of stealing $271 million from his floundering country, and served an eight-year sentence in California for money laundering and extortion. Based on records from two court cases and interviews with lawyers familiar with the matter, Reuters reported he held around $72 million in real estate hidden via a long web of front companies, centered around the Wyoming shelf.

Such cases infuriate non-Western countries. The developing world is being ravaged by international corruption—the NGO Global Financial Integrity calculates that in 2013 alone, $1.1 trillion was laundered out of developing countries. That equalled two-thirds of Subsaharan Africa’s total GDP that year. In response, the West castigates them for rampant corruption, and paternalistically sends consultants to help with “good governance.” However, the cash stolen by corrupt officials has a nasty habit of ending up in Western bank accounts, real estate, and even, in the case of a princeling from Equatorial Guinea’s bloody dictatorship, Michael Jackson memorabilia—including a crystal-covered glove. The trend skewers the narrative of a benevolent West donating to help poorer countries; in fact, total aid to the developing world makes up around 10% of the cash that disappears from it.

Much of that money is going to, or through, the US. Back in 2007, the FBI reportedly estimated $36 billion had been laundered from the former Soviet Union through US shells. Russian capital flight soared shortly after that, so it’s likely the total is much higher now. Western law enforcement does try to recover the stolen money, but it often proves an impossible task. Using GFI’s estimates, Oliver Bullough, the author of Moneyland, calculates that less than one cent of every $1,000 stolen is repatriated from the West.

As I left Pitts’ office on my second failed attempt to meet him, the receptionist told me there are around 30,000 companies registered in the small space. How can they possibly keep track of them? “Well, it’s hard, but we’ve been in business for 20 years,” she said.

None of the three Wyoming lawmakers I asked about Lazarenko had even heard of this foreign leader allegedly laundering tens of millions through their tiny state.

State representative Dan Zwonitzer, the Republican former chair of the Wyoming House Corporations Committee, was remarkably candid when we met for lunch in a sparkling-clean diner called Epic Egg. (Omelettes abounded.) A 39-year-old with an MBA and a gentle, sardonic demeanor, he sets exceptionally low expectations of Wyoming’s legislature, explaining that many local lawmakers are ranchers who take two months off every year to help out in the capitol. “You have 90 legislators and 10 of us understand corporate law—if that,” he says. “You see a 120-page bill on securities and most legislators will say, ‘If Dan likes it and Mike likes it, we’re not even going to read it. We’ll just trust ’em.'”

“That’s how things that are very flexible regulatorily are getting through,” says Zwonitzer, a Republican who in his day job is director of academic programs at the local community college. “It could certainly come back to bite us.”

He admits that he’d never heard of Lazarenko laundering money through Wyoming, and didn’t appreciate the full extent of the Panama Papers. “Wyoming doesn’t pay attention to international marketplaces in many cases. I didn’t know about Ukraine and all of the Panama Papers, and I was chair of the committee when it happened,” he says, in a measured, world-weary tone. “We’re a conservative, rural state that doesn’t think about international finance. We have two legislators that don’t even have a high school degree.”

The distrust of government in largely libertarian Wyoming is so deep that, Zwonitzer says, even if the FBI came to the state legislature and explained the dangers of corporate anonymity, it wouldn’t convince them to change the laws. That could probably only happen if Wyoming were at the center of an international scandal, he says.

“We would probably say that’s Congress’s job if international fraud is going on that’s affecting Wyoming. That’s with you guys, fix your laws,” he says, adding wryly: “Then it would probably be used as political tool about, ‘Look what the federal government is making us do.'”

He pauses.

“So, that’s how much we dislike the federal government.”

It goes deeper than libertarianism, however. Every Wyoming politico I met carried a sense of real existential angst about the state’s future. With a GDP of just $38 billion in 2017, it is America’s second-smallest economy. That’s not necessarily a bad return, since it’s the smallest state by population, but Zwonitzer estimates Wyoming has a structural deficit of around 10% of its budget. What’s more, the economy is entirely dependent on commodities—it produces about 40% of all America’s coal.

With fossil fuel prices due to plummet at some point as climate change bites, that doesn’t bode well for the future, says Chris Rothfuss, the leader of Wyoming’s three Democratic senators. “When that happens, there’ll be nothing else left for Wyoming, unless we truly diversify and attract something else.”

Zwonitzer is clearly feeling the pressure. As newly-anointed chair of the Revenue Committee, it’s his job to try to help balance the budget—not an enviable gig in a state with no business or personal income taxes. A bill that sought to lightly tax big businesses died in the Senate earlier this year, and Zwonitzer half-jokes with constituents in Epic Egg about where he might be able to scratch a dollar or two for the state coffers out of their industries. Another big drive is to attract crypto-evangelists to Wyoming, by passing radically blockchain-friendly laws.

In this context, you can understand why lawmakers might not focus on occasional mutterings of crime happening in what feels a universe away from their prairie state. The incorporation business seems a logical choice to diversify Wyoming’s economy. Wyoming is the home of the LLC and its fees are far lower than its rivals, but Nevada takes in around four times Wyoming’s earnings from corporate filings and it has double the number of business entities, according to figures from both secretary of state’s offices. Delaware eclipses both of them with nearly 1.4 million business entities, earning $1.3 billion in 2018 (around a third of the state’s budget), compared to $77 million for Nevada.

The three states are in fierce competition; some officials openly acknowledge that they copy each others’ laws. While some legal scholars and transparency activists call this competition a “race to the bottom,” with each state becoming more and more permissive to criminals, legislators looking out for their states say it’s just about staying competitive.

Wyoming looks at Delaware’s revenue, and “we tell ourselves, if we can get 5% of that our budget deficit is gone,” says Zwonitzer. “That it might cause the nation of Djibouti to go bankrupt, it doesn’t enter our mindsets…I really haven’t thought about it until I talked to you. I think of drug laundering and other things, I don’t think of whole countries having dictators invest here. It’s so far removed from Wyoming.”

Despite the risks, Zwonitzer doesn’t necessarily support tightening the state’s rules. “If we strengthen our laws, you’ll still have some level of fraud regardless,” he says.

On the sixth floor of a brown, brutalist monolith, the tallest building I’ve seen in Cheyenne, I meet the unfortunate people tasked with supervising this opaque sector: the Wyoming secretary of state’s top aides. Sitting around a conference table, wearing stern game-faces, are deputy secretary of state Karen Wheeler, compliance division director Kelly Janes, and press secretary Will Dineen. They’re loath to admit weakness in their oversight.

Janes says little, while Wheeler gives short, sharp answers. Dineen does most of the talking, his voice at times growing slightly heated as he and Wheeler push several narratives that contradict the widely held belief that Wyoming’s business laws enable crime.

The first is that this belief is “dated,” as Dineen puts it, arguing that past problems have been cleaned up. He cites as evidence that only 24 of the 240,000 companies involved in the massive 2016 Panama Papers leak were based in Wyoming. (Perhaps not coincidentally, very few clients of Mossack Fonseca—the now-notorious law firm at the center of the scandal—were American; there’s little reason to use a Panamanian law firm when you can easily incorporate anonymously at home.)

Delaware, Nevada, and Wyoming “were the three problem children to begin with, and we are the three that have been the most aggressive and proactive on addressing those issues,” says Wheeler. They argue that Wyoming has strengthened its laws in the wake of the Panama Papers, now requiring that each LLC list a real person who can answer for the company. (Zwonitzer, who was Corporations Committee chair at the time, played down this supposed legislative tightening as changing “maybe only 8 words in our statutes.”)

Their second narrative is that those criticizing Wyoming are, essentially, snobs. “There’s some sort of romanticism, this Wild, Wild West approach: ‘Wow, look at Wyoming out there on the plains with mountains and cowboys, cattle that outnumber people. What a funny thing. Those rubes out there won’t be able to handle it,'” Dineen says. “Well, that’s wrong. And that’s false.”

Thirdly, Wheeler says, “If someone wants to commit fraud, they’re gonna find a way to do it. You can have all the public registries you want. You can have all the laws in place, but if someone is determined to commit fraud, they will find a way to do it.”

Ultimately, it’s “really hard to say” whether their efforts have had any impact on crime, says Eric Amarante, a law professor at the University of Tennessee who was previously based in Nevada. “The reason why it’s hard to say is the exact reason why people can get away with it—because there’s no way of tracing this activity.”

But outside experts disagree with the claim that fraud is no longer a problem in the main US states providing LLCs. “It’s tremendous,” says Debra LaPrevotte, who spent 20 years at the FBI, helping found their kleptocracy program, and now investigates African conflict financing for The Sentry NGO. She laughs at the notion that it’s now difficult for foreign criminals to commit crimes using US shells. “Is it difficult to launder money through US shell corporations? No, it is not difficult,” she says.

Peter Cotorceanu, a lawyer who sets up trusts and LLCs for wealthy clients and says he follows strict Know Your Customer rules, agrees. “I think it’s pretty common and I don’t think it’s that difficult,” he says. “You lie to the banks but do in such a way as by using other people as frontmen…the other way of course is a corrupt banker who helps you get in the system without reporting you, even though they know the source of the funds. We know money talks, so you just have to find the right people.”

Wheeler says they conduct thorough audits on LLCs, but refuses to say how many companies their four-person team investigates, saying to do so would give valuable information to criminals. Zwonitzer says the number is less than 1% of all companies, but Wheeler insists it’s much higher. The secretary of state’s office fined the 24 non-compliant Panama Papers-linked firms in Wyoming a total of just $9,600, according to documents shown to Quartz by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which coordinated the Panama Papers reporting.

US senator Sheldon Whitehouse is scathing about the argument, made to me many times in Wyoming, that fraud will happen whatever you do. “Yeah, that’s a really good idea. I think that the other thing is you’re never gonna get rid of car accidents, so let’s get rid of the speed limit and airbags and seat belts because you can’t get rid of your car accident,” he says.

However, Wyoming is far from the only problem state. Dineen is absolutely right that the issue isn’t rooted in whether they are “rubes” from the wilderness. Every US state has lax LLC laws, and their anonymity makes it incredibly difficult to police them. Delaware, with hundreds of Fortune 500 companies, sees mass perpetrators of child trafficking, like notorious website Backpage.com, use its laws to try to avoid punishment.

The source of the issue, many critics say, is the competition between states to attract more LLCs. My next stop was the heart of Wyoming’s main rival to be the “Delaware of the West”: Reno, Nevada.

Nevada: “All for our country” (and maybe some other countries too)

If Las Vegas represents America’s Id, Reno is what happens when that Id settles for reality. If Vegas is untrammeled capitalism in its glitziest form, Reno is what you get when you take off the polish.

The self-proclaimed “Biggest Little City in the World” spent much of its history with one overriding economic goal: attract as many Californians as possible to hop over the border and gamble. Beginning in the 1990s, however, it found another way of ensnaring their money—encouraging their businesses to take advantage of Nevada’s almost non-existent taxes and headquarter or set up trusts here.

Incorporation has become a lucrative industry for Nevada. In 2001, desperate need for education funding pushed lawmakers to loosen incorporation laws even more, prompting Dina Titus, then a state senator and now a US congresswoman, to say, “We might as well hang out a shingle, ‘Sleazeballs and rip-off artists welcome here.’” (She nonetheless voted for the laws, according to McClatchy DC news agency.)

Titus was right. Reuters revealed in 2011 that three convicted criminals were managing thousands of companies in the state. In response, Nevada’s then-secretary of state promised to outlaw felons being registered agents. However, convicted money-launderers and fraudsters can still do so. (One of Reuters’ subjects still has a dozen active companies listed under his firm, whose website still lists him as director of client services.)

Even among America’s tax haven states, Nevada has gleaned a particularly dire reputation for housing scammers and fraudsters. Wyoming registered agents openly tout that using them avoids the “Nevada stigma.” In 2016, the Panama Papers cemented that perception, revealing that the Silver State was at the center of Mossack Fonseca’s US operations.

Dark money in the Silver State

The controversy seems to have had little impact among Nevada’s lawmakers, however. When I visited assemblyman Al Kramer, a Republican, in his office in the state’s capital Carson City, he barely remembered the major international scandal that had besmirched his state just two and a half years earlier. “Years and years ago, there was a situation where there was a guy who was fleecing people of their money. I think he had, I don’t know, 500 corporations and one or two was located in Nevada,” he said. “It’s called the Panama Report or something like that…I’m not being specific because I don’t remember the specifics.”

In fact, the firm created more than 1,000 companies in Nevada, some of which were allegedly used to help a pal of Argentina’s former president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, hide tens of millions of dollars earned from corrupt government contracts. Former president Kirchner is due to go on trial next month in the alleged corruption case, and the man who received the contracts has been in preventative detention for more than three years, awaiting judgement.

Another Mossack Fonseca LLC in Nevada became part of Brazil’s “Operation Car Wash” scandal, having allegedly been used to funnel money laundered from state oil company Petrobras into real estate. McClatchy reported in 2016 that one of the properties is next door to one owned by former Brazilian president Lula da Silva, who is now serving a 12-year sentence for money-laundering and corruption over the scandal. He maintains he is innocent.

Political corruption is not just a foreign issue. LLCs are a crucial cog in the vast nexus of dark money that encases US politics. Their anonymity means we often can’t find out who funds Super PACs and activist non-profits that pay for massive political ad campaigns. With the amounts of money in US politics already unrestricted, not even knowing who’s behind that cash is deeply harmful to democracy, says Anna Massoglia of Open Secrets, an NGO that researches money in politics.

“It’s very dangerous not to know who’s behind political messaging when you go to the polling place—who’s shaping your view of the candidates?” she says. “LLCs become easy vehicles to funnel money into the political system while keeping the source of that money anonymous and keeping voters in the dark.”

She also points to a $1 million donation made to president Trump’s inaugural committee by a secretive LLC called BH Group, which is reportedly registered to a “virtual office” in Virginia and was created exactly four months before making its donation. It’s unclear what the LLC’s actual business is, though it has received several large payments from opaque conservative political funding groups, according to Massoglia. There’s no indication the company has done anything illegal.

Federal prosecutors are investigating the inaugural committee, reportedly looking at money laundering and election fraud. They have subpoenaed swaths of documents, and are interested in whether foreigners donated to the committee, the New York Times reports. When the subpoena was issued in February, a committee spokesman told the Times it would cooperate with the probe and was reviewing the subpoena.

Beyond just shady influence, there are fears LLCs could be used for outright bribery. A USA Today investigation in 2017 found that at least seven luxury condos worth millions of dollars had been sold by president Trump’s company to anonymous LLCs since his election a few months earlier. Another Nevada LLC had spent $3.1 million on Trump properties during the election, and seemingly listed a false address. USA Today linked three people to the firm, two of whom didn’t reply to its requests for comment. A third reportedly hung up when a reporter identified himself over the phone. No one connected to the Trump Organization would answer their inquiries.

Transparency advocates worry that buying the president’s assets could be a way of getting in his good books, or even paying him off, without the public ever knowing about it—however, there’s no evidence that the Nevada LLC in question, or any other companies, have done so.

Speaking from a regal blue armchair, Kramer lamented that Wyoming was stealing a march on Nevada, after the latter upped its incorporation fees. “I see it as the golden goose and I don’t think we should be slaughtering the golden goose,” he said.

Kramer, a retired former city official, spoke authoritatively about how little money laundering was going on in the whole of the United States, let alone Nevada. “The US government has tightened up so much and the banking regulations are such that I think it would be very difficult to launder much,” he assured me. “If you’re talking $1,000 or $2,000, yeah, you could probably have a cash business and you could probably bring that much in and put it in your bank account every now and again under the radar.”

Before our meeting, I had hunted through some legal filings and found a rather different story. Just a few weeks earlier, US prosecutors had accused one of the alleged perpetrators of the 1MDB scandal—the theft of billions of dollars from the Malaysian people—of using a Nevada shell company to buy a $15 million Beverly Hills mansion with stolen cash.

Kramer was unfazed when I told him about the case. First, he denied it had happened. Then he suggested he usually thinks of money laundering as using cash, not wiring stolen money. Then, he claimed that title-insurance companies for real estate were very stringent. He then returned to how rigid the banks’ customer checks were. Eventually, Kramer concluded: “I think there’s a weakness in the banking…they want the business so bad they’ll overlook some of the details. We know that from the lending scandals we had 10 years ago where banks were loaning money without even a paystub.”

Trust (but don’t verify)

After our meeting, I went for a walk through Carson City. As a mountaineer and frontiersman, Kit Carson would no doubt have loved the setting of the city that bears his name. It’s an exquisite spot—a thin plain encircled by breathtaking snow-topped mountains. Whether Carson, a genocidal legend of Western folklore, would have enjoyed the town itself, however, depends on his feelings about strip malls filled with lumpen brown boxes on roaring highways.

On the town’s outskirts, I found 3064 Silver Sage Drive, the home of GKL Registered Agents and, by proxy, the LLC through which the aforementioned $15 million Hollywood pad had allegedly been bought. Four registered agents in Carson City administer around one company for every four of the city’s residents. GKL, the biggest, housed over 4,000 companies in a small bungalow, sitting in the shadow of the mountains before me. The owner, his receptionist had told me on the phone, didn’t want to talk to me. (They also didn’t reply to a subsequent emailed request for comment.)

While reporting this story, I found just one registered agent who would.

Robert Harris splits his time between prolifically setting up companies from his one-story home in the little Nevada town of Fernley, and writing self-published books about the Rapture, the radical evangelical Christian doctrine. A genial man in his 70s, he worked as a bartender until he was about 50, at which point he says bars began refusing to hire anyone who wasn’t an attractive young woman. A lawyer friend taught him the incorporation business, and three and a half thousand companies later, he’s still going.

Harris isn’t troubled by the notion that he could be unwittingly helping criminals launder their money. “I don’t investigate people before I do business with them—nobody does in my business. I don’t get paid to investigate people, I get paid to make a living to take their business,” he says over the phone, apologizing that personal reasons stopped him being able to host me.

“Do I ever worry? No, because I don’t think evil of my clients, my customers. Most are very good people, I think. How would you investigate them, anyway? They call and say, I’d like to set up a corporation in Nevada. I say fine, what’s your company name? Do you do money laundering?”

His views on the matter are, like Kramer’s, untarnished by criminal indictments and media reporting. “I’m not really familiar with the Panama Papers. Maybe I like heard about it or something, but it didn’t affect me so I wasn’t overly worried about it,” he says.

They’ll take Manhattan

My final stop in the world’s biggest tax haven was closer to home—about 30 blocks north of Quartz’s New York office. Jutting out behind the Rockefeller Center, one of Manhattan’s art deco jewels, is a more forgettable brown-tinged skyscraper, with a Nike store cobbled onto its ground floor. On street level, an open-air foyer contains a jumble of mirrors, metal panels, and an LED ceiling that shifts color between pink and lime green. The combined effect is that of a trashy nightclub trying to seem posh.

This is 650 Fifth Avenue. For decades, the building “gave the Iranian government a critical foothold in the very heart of Manhattan,” then-acting US attorney for Manhattan’s Southern District Joon H. Kim said in 2017. Iranian government-linked entities had gotten away with owning the building, valued between $500 million and $1 billion, by holding it through a web of shell companies. The likes of Juicy Couture, Godiva Chocolate, and Starwood Hotels had inadvertently been paying millions in rent to US-sanctioned Tehran, right under the feds’ noses.

After nine years in court, the US government eventually won the right to seize the building two years ago. The case has set off serious national-security jitters. Previously, worries about opaque ownership of US properties centered around the ethics of taking potentially stolen money and the plutocratic spending’s knock-on effects on local housing markets. The Iran case awoke another question—what if other foreign powers or terrorist groups are renting out American buildings as slush funds to have cash in the US that can fund nefarious operations?

650 Fifth Avenue is “symbolic of a more systemic problem,” says Dennis Lormel, the former chief of the FBI’s financial crimes program who traced the funds used for 9/11. He says he wouldn’t be surprised if Hezbollah has similar US shell companies, funding terror cells potentially ready to be activated.

The issue is shockingly widespread. In 2016, the Government Accountability Office couldn’t figure out who owned one-third of the buildings leased by an arm of the US government to house high-security operations. Just let that sink in: the most powerful country in the world doesn’t know who owns the buildings where it conducts secret and sensitive operations. These included FBI and Drug Enforcement Agency offices. The GAO did manage to trace that China and Israel, both of which have fearsome security services, were among the countries anonymously leasing buildings to the US government.

Kicking the anthill

Countless pieces of legislation have tried to force some transparency on LLCs in the past decade, but all have died quick and quiet deaths. In the wake of Russia’s attack on the 2016 election, however, there’s been increasing sense urgency in Washington to try to patch up the holes bored into US national security by corporate secrecy.

Several bills are floating around Congress now, with supporters among powerful Democratic and Republican lawmakers, and even from Treasury secretary Steve Mnuchin, who once failed to disclose to the Senate Finance Committee that he was director of a Cayman Islands investment fund. (He said the non-disclosure of the role and various assets was “unintentional,” and caused by the complexity of financial disclosure forms.) These efforts are less ambitious than moves seen in Europe, where the UK has a completely public—albeit flawed—registry of the owners of every company, and the EU is instituting a similar system.

Senator Whitehouse, who authored one of the US bills, says he’d like to see that system in America, but acknowledges there’s not the political will for such openness. Instead, current plans would force company owners to prove who they are by showing government-issued ID. That information would be sent to the authorities, so law enforcement could access it when they have good reason to do so. “But it wouldn’t be completely transparent to any curious person who happened by, so we’ve actually been a bit more conservative in the effort to try to get this passed,” he says.

I met mixed reactions when raising the legislation out West. Wyoming’s secretary of state’s office supported the federal government sharing more information. They called for the IRS to give data to the Treasury, and Dineen incorrectly thought the Treasury already collected beneficial ownership data.

Others said this would violate their privacy. Some based their arguments in libertarian ideology. Others noted the federal government’s history of being hacked. Some seemed downright paranoid—one amiable Wyoming lobbyist emailed me saying, “the potential for abuse of this information by the Government for political or other reasons is immense.”

Whatever happens, Tax Haven USA will have plenty of fight left in it. There are other ways for foreign criminals to funnel cash into the US, experts say, including through trusts, hedge funds, and venture capital. The money sitting in trusts in just a handful of states including South Dakota and Nevada could add up to more than $1 trillion, estimates Oliver Bullough in Moneyland. That money “is hiding from sight, avoiding taxes and oversight, and will be able to do so until long after our great-grandchildren are dead,” he writes.

Gary Kalman, director of the FACT Coalition, the lead lobbyist for the LLC transparency law, admits their legislation has flaws—notably that lawyers and registered agents wouldn’t have to figure out whether companies’ owners are clean. He calls the bill a “foundational step.”

“I view this as an anthill,” he says. “If you bend down and mess it up with your hand, all the ants come scurrying out, and it allows law enforcement to follow the ants and see where the next schemes of how to evade laws are.”