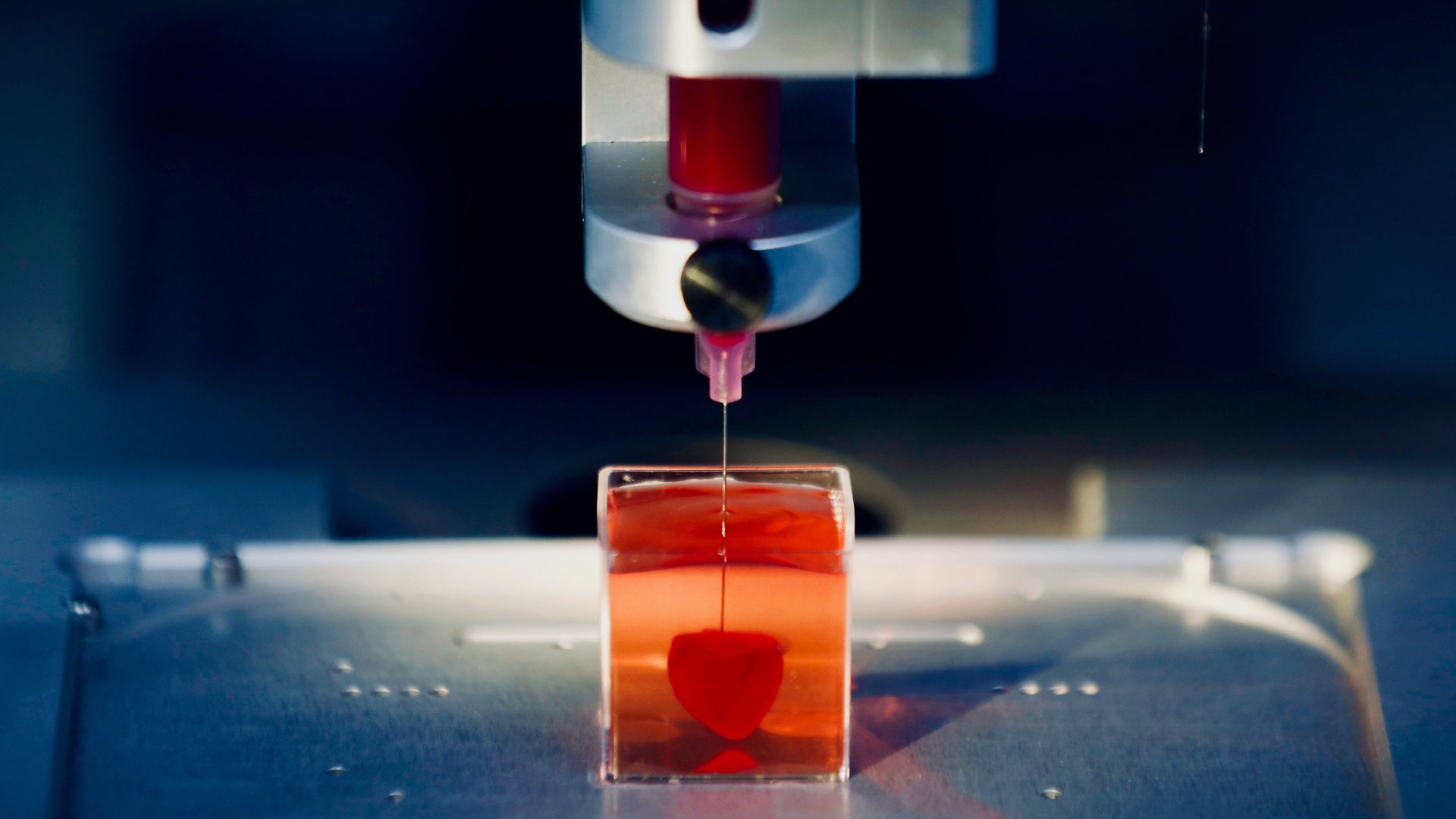

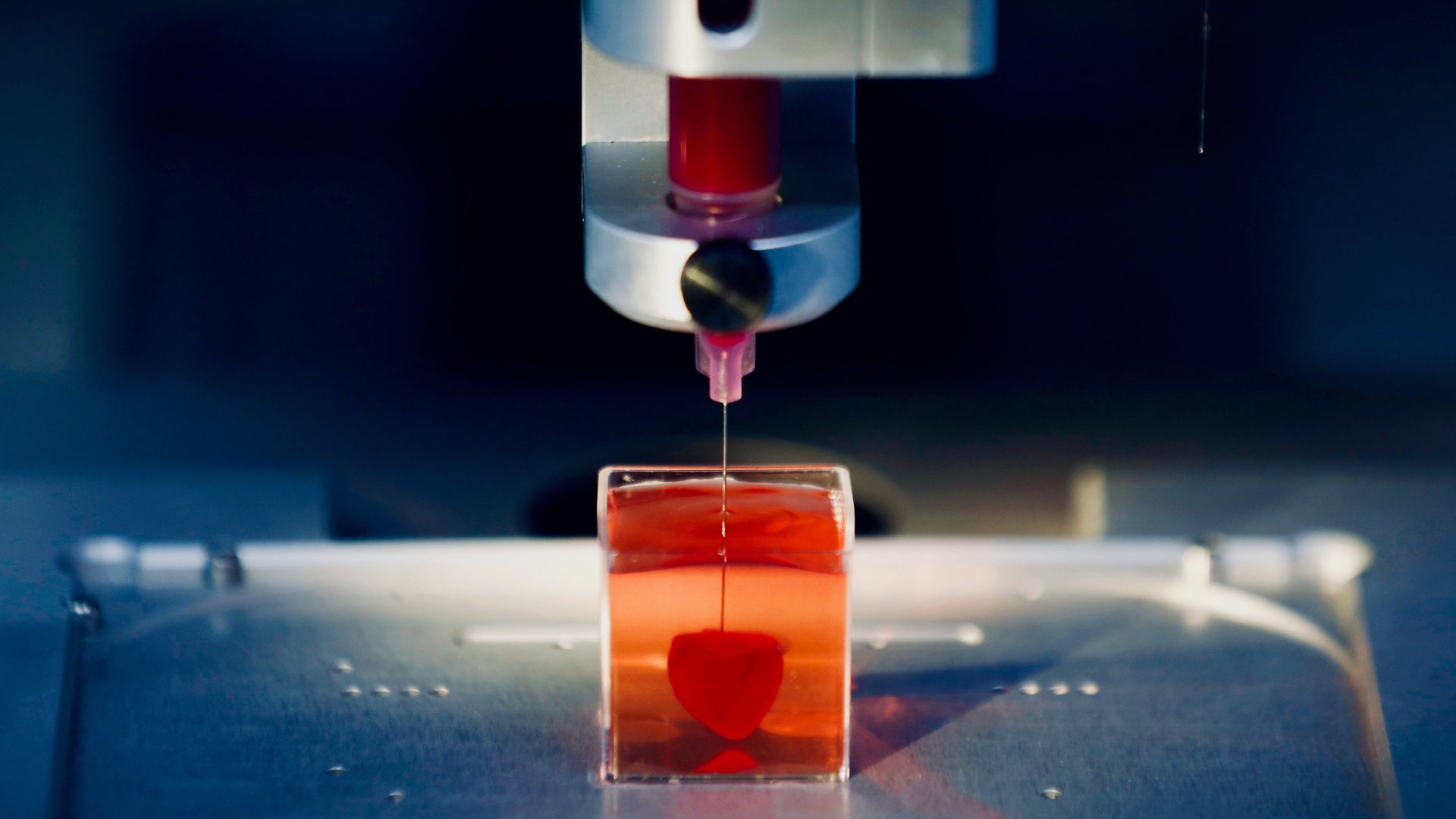

Scientists say they just created the world’s first 3D-printed heart

Today, if you need a heart transplant, you must wait for an available and suitable organ from someone else’s body. The wait time for a donation can be dangerously long and transplants don’t always take. However, there may come a day in the not-too-distant future when doctors simply 3D-print a replacement heart, or other body parts, creating a customized alternative made of bio-inks whipped up using your fatty tissue.

Today, if you need a heart transplant, you must wait for an available and suitable organ from someone else’s body. The wait time for a donation can be dangerously long and transplants don’t always take. However, there may come a day in the not-too-distant future when doctors simply 3D-print a replacement heart, or other body parts, creating a customized alternative made of bio-inks whipped up using your fatty tissue.

On April 15, scientists from Tel Aviv University in Israel announced in a paper published in the German journal Wiley-VCH that they have made progress toward that goal. They just 3D-printed a heart. “This is the first time anyone anywhere has successfully engineered and printed an entire heart complete with cells, blood vessels, ventricles and chambers,” corresponding author Tal Dvir told Ha’aretz (paywall).

It’s exciting news. Still, scientists are still a long way off from actually making this printed heart function like the real thing and transplanting it in a living creature.

The new experimental organ is tiny—about the size of a rabbit’s heart, or half the size of your thumb, say. It doesn’t yet beat, which means it can’t pump blood, and that of course is an extremely important function.

Nonetheless, this development is remarkable. The researchers made their organic ink for 3D printing using human fatty tissue. They separated the tissue’s cellular and non-cellular components, creating stem cells which they then directed to grow into either cardio or endothelial cells. The non-cellular components and “programmed” cells together formed the basis for a “hydrogel,” or “bio-ink,” used in the printing process.

The researcher’s creation is in the maturing stage now, as they figure out how to coax this tiny ticker into functioning like a real organ, teaching it to beat.

In theory, in the future each printed heart would be printed with ink derived from tissue of the organ’s eventual recipient. Because it’s made from the recipient’s own cells, the body is less likely to reject the foreign object as it won’t be quite as alien as an organ that once resided in someone else’s body.

This technology won’t be viable for real-life transplant scenarios for some time—if ever, depending on researchers’ future successes. But there’s another upside to the new development. The new study also discusses the scientists’ efforts to make cardiac patches printed from human hydrogels.

Patches are portions of a whole organ used for repairs—think of them like engine parts. Until now, no one has been able to print them in a single step. Instead, previously, researchers printed various aspects of each part and tried to combine those elements to make a functioning whole patch.

The researchers at Tel Aviv University, however, printed complete patches in one go. The benefit of this method isn’t just efficiency. These patches are also made from people’s fatty tissue and so are personalized, “fully match[ing] the immunological, biochemical and anatomical properties of the patient,” the study states.

Because making a patch is not nearly as complex as creating a whole, functional organ, it seems likely that these heart parts will reach the next research phase faster than the entire organ and, ultimately, be used in humans sooner.

For now, however, the scientists still have to mature and perfect their experimental heart and parts. If they succeed, they’ll be ready to print more organs and start transplant studies on rodents. Assuming that goes well, human studies will be next. Dvir tells Ha’aretz it will probably be another decade yet before organ printing is fully developed for use in humans but he thinks this method is the future of transplants.