DNA ancestry tests distort our view of race and humanity

Modern genetics should have obliterated the very concept of race.

Modern genetics should have obliterated the very concept of race.

The science, which crystallized in 2000 with the near completion of the first-ever entire sequencing of the human genome, has provided nearly indisputable proof that all humans are, in the big picture, identical. Approximately 99.9% of our genomes are uniform, and within the remaining fraction of a percent, there is no such thing as “black” or “white” DNA. Superficial qualities like skin, hair, and eye color indicate no significant biological differences.

And yet, the rise of direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic ancestry tests has had almost the reverse effect. Through flashy advertising, these companies promote the idea that our DNA is capable of defining our identities. Unwittingly or not, they fuel an idea white supremacists have falsely propagated for centuries: that “race”—the concept that superficial attributes translate to actual biological differences—exists.

For example, in a 2013 thread on Stormfront (a neo-Nazi forum), one white supremacist wrote that a genetic ancestry test he took had come back with results showing markers of Druze and South Indian heritage. Others responded on the thread with messages of consolation, telling him it was likely the result of a sexual assault.

As long as customers take genetic ancestry tests at face value—even for entertainment purposes only—they’re complicit in giving neo-Nazis a way to wield genetics for their heinous cause.

The science behind ancestry tests checks out in theory.

To generate these reports, the company providing them will compare about 700,000 of your specific genetic mutations with its database of “reference genomes”—genomes of people who self-reported their own heritage to the company. Because we get our genetic code from our parents, grandparents, and so on, we all have benign DNA mutations likely inherited from our ancestors. If companies can isolate which of these mutations tend to occur in large groups of people who all say they come from the same part of the world, they can approximate ancestry.

In practice, the process is very imprecise. First of all, while 700,000 mutations sounds like a lot, they account for less than 1% of your DNA—you’ve got about 6 billion total base pairs. Second, self-reported data of any kind is a red flag, since there’s no way to ensure that the families of reference-genome providers are actually from where they say they are from.

Further, these tests can’t account for shifts in geopolitics, so, at best, they can only tell you which modern-day countries correspond with the regions in which your ancestors lived. In other words, if you get a report saying that you have 32% Spanish ancestry, the most accurate way to think of that statement is “I share some of the known variance in my genome with people who, at some point in history, lived in what is now Spain.” (23andMe does provide estimates of when ancestors lived in different regions, but these estimates span nearly a century.)

All DTC tests that promise ancestral information provide public information about their methodology, along with acknowledgements of these major caveats. And yet, these disclosures are easy for customers to ignore when they’re given flashy, easy-to-read reports practically screaming “we know your ancestry!”

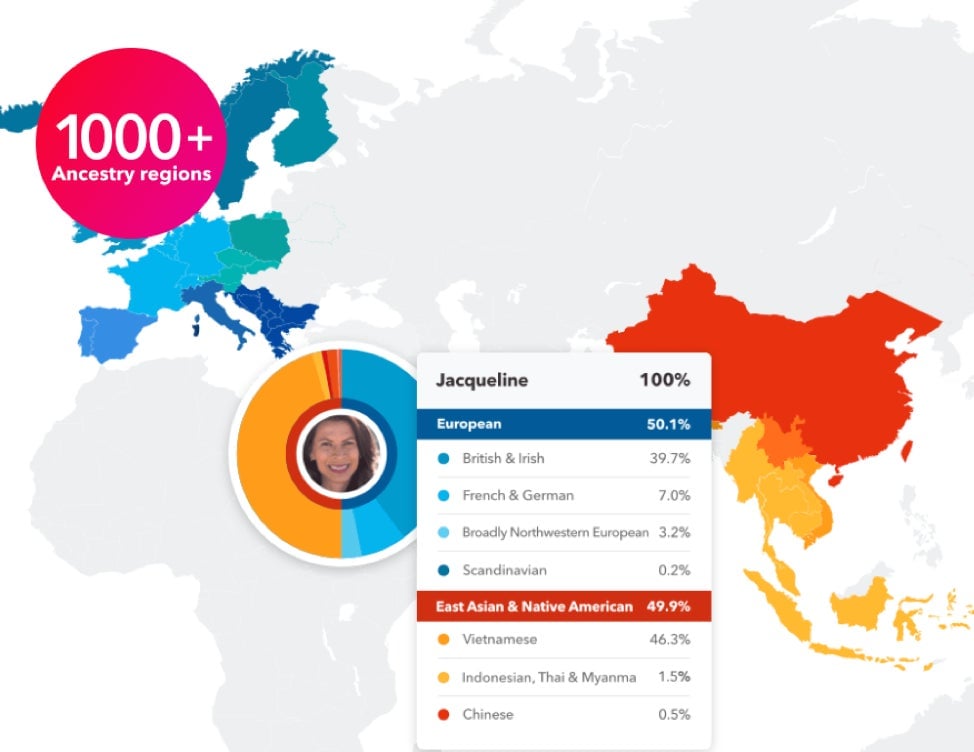

Take this report, generated by 23andMe:

It’s clear, it’s colorful—and it makes it look simple to break down all of our DNA into discrete slices of a pie chart.

The simplicity has helped to make these tests hugely popular. Between January 2017 and January 2019, the number of people worldwide who had taken any kind of DTC genetic test jumped from 4.5 million to 26.5 million. Not all of these tests are for ancestry alone. 23andMe, for example, also offers users DNA-based health and wellness information. But the largest of these companies, with just under 15 million users as of January of this year, AncestryDNA, does not. It offers ancestry profiles, and the promise that it could help users connect to family members.

Ads and marketing materials for these companies often tout their services with an appealing kumbaya feel: “Genetics just got personal,” reads a 23andMe banner on its site as of April 24, alongside testimonials of customers reporting a sense of closure from learning clues about their ancestral identities. AncestryDNA ran a TV ad in the mid 2010s featuring a person who, upon learning that he is Irish and Scottish instead of German, trades in his lederhosen for a kilt. The same company ran a promotion in March this year encouraging people to buy its service in order to find their Irish roots—presumably so they could better enjoy St. Patrick’s Day. Just last week, the company was forced to remove a similar ad that romanticized a slavery-era interracial couple.

In January of this year, the airline company Aeromexico achieved overnight virality thanks to a PR stunt in which white US citizens shared their myopic views of Mexican culture before receiving discounts on flights to Mexico based on their percentage of “Mexican DNA.” Hilarity ensues when the husband shoots a jealous look at his wife who is “more Mexican” than he is, not because of the savings she gets.

If a person has no clue about their genealogical background, a DNA test can point them in the right direction. Sometimes, these tests can even help people track down family members they didn’t know they had. But often, the marketing for these tests conflates identifying vague genetic markers with finding a core identity. In reality, we form our identity as we grow up; to say it’s actually something that’s been secretly hidden from us, tucked away in our cells, has some entertainment value but is a dramatic oversimplification.

In the end, offering flight discounts based on what amounts to an arbitrary ancestry assignment isn’t necessarily harmful. But there are destructive ways to wield these genetic ancestry tests. In 2013, white supremacist Paul Craig Cobb went on The Trisha Goddard Show, a cable talk show, while in the middle of a campaign to incorporate a small town in North Dakota as a white ethnostate. On the show, it was revealed that 14% of his genetic makeup could be traced to sub-Saharan Africa (the remainder was European).

It was supposed to be funny, and maybe even a moment when Cobb would reconsider his beliefs in white supremacy. Rather than giving up his racist ways, though, Cobb doubled down. Facing embarrassment among white supremacist networks, Cobb took another ancestry test, hoping its results would better align with his beliefs. He’d later post his new test results on the designated hate group’s site—they seemed to exonerate his whiteness with the exception of a “3% Iberian thing.” The other test results, he argued, were not scientifically accurate.

Today, white supremacists conflate genetic ancestry with race to support the false idea that they are superior to other humans. It’s the latest iteration of a long history of abusing biology to justify the concept of “race.”

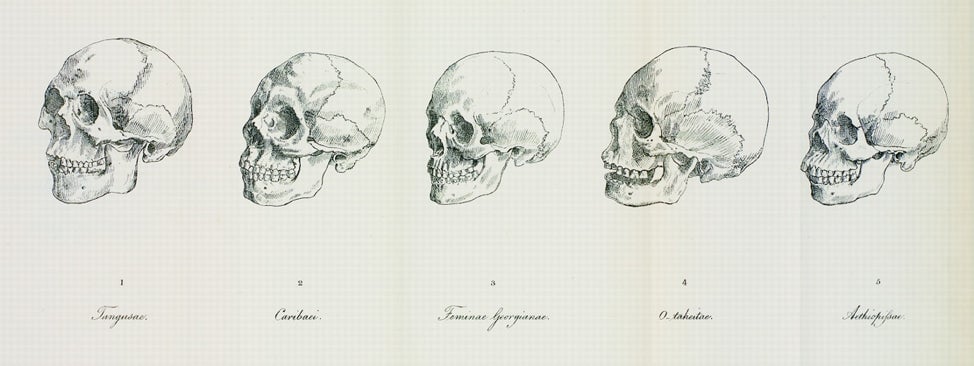

One of the most famous is phrenology. In the 1700s, a German anthropologist named Johann Friedrich Blumenbach created a “taxonomy” of supposedly race-based biological features that separated the known world into five groups, based on skull size and shape, and therefore brain regions.

Later that century, in 1796, German physiologist Franz Joseph Gall proposed that the brain was composed of “organs,” or sections, that represented different abilities, and that these compartments were responsible for the shape of one’s head. Therefore, he suggested, measuring a person’s head was a meaningful aptitude test.

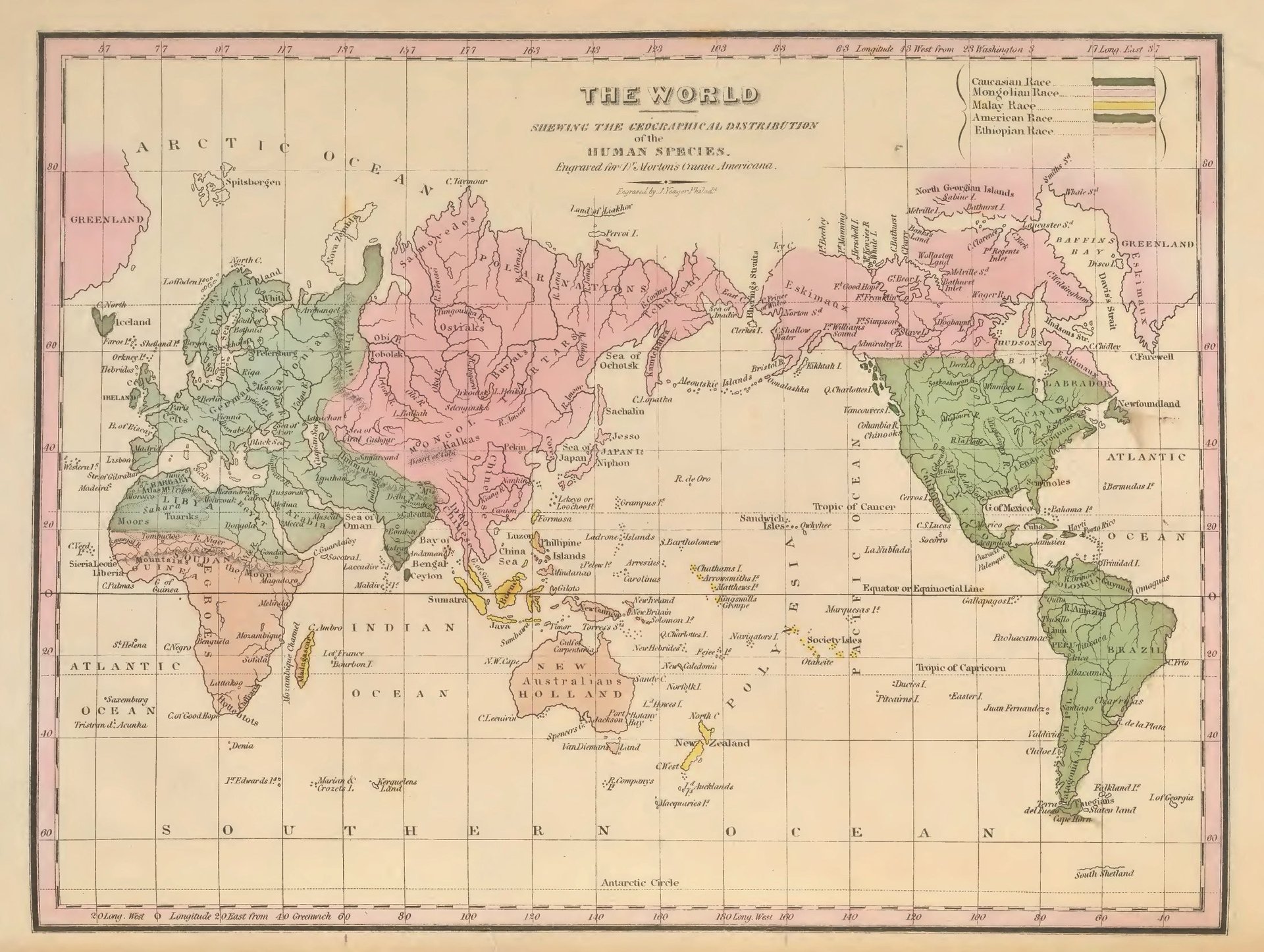

These misguided concepts had staying power. In Samuel Morton’s 1839 work Crania Americana, there are clear echoes of Blumenbach’s ethnic taxonomies. For example, in one map included in the book, Morton divides the world into racial regions based on measurements of the skulls taken from people from those regions. He also ranked these various skull shapes by their supposed intelligence.

Morton incorrectly asserted that the white populations with the largest and ovoid shaped heads attained, “the highest intellectual endowments.” Widely heralded as fact when it was published, Crania Americana influenced the common and political thought of the day. By the 1830s, it was commonplace in the US to believe that “race” and its physical characteristics dictated intelligence. Morton’s racist beliefs about indigenious Americans made its way into Andrew Jackson’s policy of “Indian Removal” and white US doctors regularly conducted phrenology readings, analyzing head shape among other physical traits like skin tone and texture, height, and weight. As recently as the middle of the 20th century, phrenology was called on by Nazis in Germany as part of their “proof” of the superiority of the Aryan race.

Companies that offer genetic ancestry testing do not claim to look at “race”; they strictly deal with ancestry. However, their test results showing a person’s identity broken down by discrete geographies uncomfortably recalls Morton’s maps. And they have a similar effect.

“The one thing that these tests promote is the idea of racial purity,” says Arica Coleman, a historian whose research focuses on the treatment of African Americans and Native Americans in the US. “If I can tell you that you are 30% this, 30% this, and 10% this, then I have to know what the 100% is.”

In other words, when we are faced with portions of different categories, we tend to inherently rank and assign a value to them. No ancestry is better or worse than any other. But when genetic tests falsely imply that heritage can be divided into a clean pie chart, they give rise to the idea that falling more into one group could be “better.”

Most people who take a genetic ancestry test know that who they are, ethnically and culturally, depends on how they are raised—not their DNA. Yet buying into the notion that the percentages these tests provide mean anything substantial about ancestral background makes us complicit in supporting a potentially racist idea system.

A recent, highly publicized example of this kind of complacency in action was when Elizabeth Warren, the senior US senator for Massachusetts, took a DNA test in an effort to prove that she had a Cherokee relative.

In October of 2018, Warren announced that private DNA testing had revealed she likely had Native American ancestors six to 10 generations ago. Technically, this proved that she had not necessarily lied about having indigenous people in her family tree. But on a 1986 registration card for the Texas state bar, obtained by the Washington Post, Warren had written that she was “American Indian,” despite not having close contact with anyone in any Cherokee tribe. (In 1980 and 1990, the official US Census had both “white” and “Indian”—meaning Native American—as options for participants to identify their race.)

For indigenous North Americans, ethnic identity cannot be simplified into a few genetic markers, explains Kim TallBear, a professor of Native studies at the University of Alberta and a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, a Dakota tribe. Although each indigenous tribe has unique requirements for membership, tracing the lineage of actual family members—not just identifying a statistical likelihood of belonging—is always important. “The main thing with genetic ancestry testing is that it’s pointing back to distant ancestry and people without names,” says TallBear. “We want names. And they have to be names within a tribe.”

Ultimately, Warren issued an apology (paywall) to the leaders of the Cherokee Nation for taking a DNA test to prove her connection to Native Americans. Critics said that by doing so, she gave weight to the idea that genetic ancestry tests alone could prove race or identity.

Warren is not a white supremacist or neo-Nazi. But because genetic ancestry tests promote a narrow, European idea of identity, TallBear says, they are all inherently based on a form of white supremacy.

And sometimes, people go even further than Warren, and use DNA tests to claim a cultural identity. A small study published in June 2018 found that 33% of people who took ancestry tests changed their stated identity based on the results—and that the majority of these people did so because the results offered new identities from which they could benefit. Most often, white people embraced the ancestry of a non-white culture, likely in an attempt to make them appear more interesting, Wendy Roth, a sociologist and lead author of the paper, wrote in the Conversation.

“Certain Americans who find whiteness as generic and aspire to find something unknown about themselves are more likely to take the test and more likely to change their identity,” says Aaron Panofsky, a sociologist at the University of California-Los Angeles, who did not work on Roth’s study. It’s essentially white people “appropriating the good stuff,” the desirable parts of being a minority, “without suffering the bad stuff,” the lifelong discrimination and microaggressions that come with being a person of color, says Panofsky.

Getting discounts on a flight to Mexico because you have genetic markers of Latinx ancestry is a perfect example. It’s certainly possible to have those markers without having to walk through life as a Latinx person.

This kind of cultural appropriation is typically something only white people can get away with, TallBear notes. “White people can claim to be anything they want; they know it’s going to be accepted,” she says. “[Many] black people have European ancestry… but they don’t get to walk around claiming they’re white.”

White supremacists’ use of DNA tests to prove their racial purity is a sort of mirror image of these cultural appropriators. White supremacists also feel having a particular set of genetic variations puts them at an advantage over others. In their case, though, it’s not just insidious: it’s dangerous. They use their supposed genetic identity to rationalize violence against others.

In recent years, white nationalists have publicly and privately had to wrestle with genetic ancestry results showing they have DNA links to what they consider “inferior” heritages. Instead of finally disavowing their racist ways, though, these racists have adapted their belief systems to accommodate and appropriate an immature science.

Between 2014 and 2016, Panofsky and his colleague Joan Donovan, a social scientist at Harvard University, spent hours on Stormfront, a white-supremacist online forum, looking through 3,070 threads on some 600 posts in which users revealed the results of their genetic ancestry. The results of their study—which have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, but are available in preprint online—show that most posters interpreted genetic ancestry tests in one of four ways.

First, if a Stormfront user’s genetic ancestry test revealed mostly European heritage, the test was considered valid.

Second, if their results showed genetic markers from all over the world, Stormfront users were most likely to reject the results, claiming the companies were part of a Jewish conspiracy (they aren’t). Or they’d argue that the statistical analysis underlying these tests was wrong in some way, and paper genealogy—piecing together family lineage through birth certificates and marriage licenses—is the best way to confirm “racial purity.”

“My advice is to trust your own family tree genealogy research and what your grandparents have told you, before trusting a DNA test,” one user wrote, responding to another user who shared a genetic-ancestry test showing less than 100% European heritage. “These companies are quite liberal about ensuring every white person gets a little sprinkling of non-white DNA (we know who owns and runs these companies).”

The third way Stormfront users interpreted their unsatisfactory genetic ancestry results was that they were a sort of come-to-Jesus moment for white supremacy. Even their own rules on “whiteness”—that is, to be entirely non-Jewish and of European decent—couldn’t possibly be upheld, some racists said. “A new standard will have to be set based on modern technology,” one user wrote in 2013. “Strict adherence will result in very few individuals qualifying for Stormfront.”

Fourth, in some cases, neo-Nazis who didn’t like their DNA test results would argue that genetic ancestry testing confirms that there is not one definition or origin of whiteness, but several, each with a basis in a different part of the world—all of which are still superior to people of color. It’s an idea unnervingly reminiscent of Crania Americana.

Instead of inventing pseudoscience in a way that most geneticists would strongly disagree with, “white nationalists have taken it upon themselves to appropriate this knowledge, bring it into their field, and write it into their own studies of what genetics mean,” says Panofsky. They’re not entirely fabricating science, but they’re manipulating it to serve their needs. It’s unclear how they will use this kind of science to fuel their horrific cause in the future.

Only a small portion of the people who take genetic ancestry tests are white nationalists. However, the reason they can engage with these tests in this new way comes back to the way they’re marketed. By advertising that customers can figure out their exact ancestral breakdowns, they’re allowing racists to buy into the idea that there is specific, superior DNA that creates a “white” breakdown.

And anything that encourages racism is dangerous. In the last decade, white supremacists have become increasingly emboldened to commit acts of terror all over the world, most recently at a mosque in New Zealand where, on March 15, a 28-year-old self-proclaimed “white supremacist” from Australia opened fire and killed 50 people and injured dozens more.

This doesn’t mean genetic ancestry tests are inherently bad. There is nothing wrong with trying to search for clues about your family history through genetic markers. These tests can’t definitively say what your ancestry is, nor can they be a substitute for a cultural identity, but they can point you in the right direction.

Unfortunately they can also distort our views of humanity, especially when they market themselves as an opportunity to figure out a person’s exact ancestral breakdown. Because when we look at only what makes us biologically unique, we forget that we’re all 99.9% the same.