Big ancestry testing companies fail people of color—but smaller organizations can help

Most people can get a sense of who they are and where they came from by comparing what they glimpse in a mirror to old family photos. Seeing physical traits passed down through generations, like the shape of a nose or eye color, can give us a sense of belonging.

Most people can get a sense of who they are and where they came from by comparing what they glimpse in a mirror to old family photos. Seeing physical traits passed down through generations, like the shape of a nose or eye color, can give us a sense of belonging.

Conversely, missing those connections can make someone feel lost.

Wendi Cherry is black. She has a straight nose with a small ring on the right side, and long hair that she wears in locks that go from dark to light. Before she was born, a black family living in New Jersey arranged to adopt her. Her adoptive family—mother, father, and an adopted older sister—all had much darker skin than she did. “Kids would tease me that my sister was not my sister because her skin didn’t look like mine,” she says.

She wanted the sense of belonging that comes from recognizing oneself in the way a biological relative looks. “I got the African Ancestry test as a gift,” she says. “I wasn’t getting that information from my biological parents, but that didn’t stop the yearning to figure out who I was.”

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing services can help surface family members or ancestral heritage for many people like Cherry, who were adopted or had some other disruption in their family trees. African Ancestry, however, is unique in that it has the largest database of African genetic material. It can provide answers for users who are otherwise unserved by other direct-to-consumer testing companies.

Although large DTC genetic testing companies have huge databases of customers that could be an asset for those searching for their families, their homogeneity is a pitfall. The companies do not publish detailed breakdowns of customer base, but we do know that the majority of people who have taken these tests are of European decent. In fact, roughly 60% of people of European heritage (paywall) in the US have third cousins in current genetic databases. But because there are fewer reference genomes of people known to be from countries in Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia, it’s not always easy for people of color to find relatives through a simple cheek swab.

Many large genetic-testing companies are trying to swell their client numbers in order to increase the diversity of their databases to better serve minority customers. But even the biggest, like 23andMe or AncestryDNA, can lack the nuanced cultural knowledge that some of their customers need. Those who are adopted or are descendants of people who were enslaved, for example, don’t just need to find genetic matches in a database, but also to wade through specific types of trauma to find answers about their biological family history. As a result, smaller companies and nonprofit groups, run by the same people they serve, have emerged to fit these voids.

Cherry loves her adoptive family, but was always curious about her birth parents. “I used to say, ‘I am this astronaut floating out into space by myself,’” she says. “I didn’t look like anybody.”

In 1988, Cherry got in touch with her adoption agency, and they began to work together to find her birth family. She found one biological sister who had also been given up for adoption, roughly a year before she was. She also identified her birth parents, and in June 1989, she and her sister decided to try to connect with them.

Although Cherry and her biological sister hit it off quickly, it was harder to form an immediate bond with her birth parents and the four children—also Cherry’s biological siblings—they raised. When Cherry and her sister were born, some two decades prior, her birth parents decided they weren’t in a place to raise the girls the way they thought the children deserved. But Cherry’s parents never felt fully at ease with this decision, and when Cherry and her sister came back into their lives, they became a reminder of the guilt they had felt at the time. Pressure from their church made them feel ashamed of their decision. “They didn’t want to be found,” Cherry says.

That initial emotional gulf, combined with the fact that Cherry’s biological parents didn’t seem to know much about their heritage themselves, led Cherry to decide they weren’t going to give her the answers about her ancestry she wanted. Nineteen years later, in 2007, she decided to send her DNA to African Ancestry.

African Ancestry was created in 2003 by biologist Rick Kittles and entrepreneur Gina Paige. “Damn near all” black Americans have an interrupted family tree due to the transatlantic slave trade, says Paige. “We as black Americans became the original victims of identity theft.”

Starting when he was a PhD student at George Washington University in 1990s, Kittles spent more than 10 years collecting genetic samples from various ethnic groups in West Africa. At first he was driven by a desire to learn more about his own heritage; the company started with a primary focus of obtaining samples from African countries invaded by Europeans for the slave trade. Now, African Ancestry boasts what it says is the world’s largest database of African DNA, with 33,000 lineages representing 40 countries and 400 ethnic groups (pdf) within those countries. (For comparison, AncestryDNA and 23andMe can provide ancestry estimates from nine regions on the African continent.)

To estimate where a person’s genealogical relatives lived, DTC genetic-testing companies compare a small amount of variants on that person’s DNA to variants from individuals known to be from certain parts of the world. They can also trace direct parentage lines from mitochondrial DNA (or “mtDNA,” passed down from mothers to all their children), and Y-chromosome DNA (passed down from fathers to any child with a Y-chromosome).

African Ancestry primarily tests and catalogues mtDNA and Y-chromosome DNA, to assess maternal and paternal lineage. When Cherry took the African Ancestry test in 2007, she found that, through her maternal lineage, she is a descendant of the Mafa people of northern Cameroon.

Cherry doesn’t have a Y-chromosome, so was unable to trace her paternal lineage. A few years after sharing her maternal lineage with her biological family, though, her father agreed to take a maternal and paternal lineage test. His mitochondrial DNA test revealed that he was from the Temne tribe in northern Sierra Leone. His paternal line, though, was not African at all—it was German.

It’s common for black Americans to have some kind of European ancestry. “This was probably a case of a German human trafficker (read: enslaved person owner) raping my African grandmother beginning this family line,” Cherry wrote on her blog in 2015, the year her father got the results of his DNA test.

Nevertheless, finding her African identity roots brought Cherry a sort of peace. “It allowed me to stand taller and know who I was,” she says. She has since become heavily involved in the Cameroonian community in DC.

African Ancestry’s database is unique, and so are its privacy practices: unlike many other DTC genetic-testing companies, it doesn’t store clients’ DNA. This means that while it can trace maternal and paternal lineage, it cannot identify individual family members for customers, like larger companies can.

Those who use African Ancestry see the added privacy as a perk. “Our customers wouldn’t want their information sold or shared,” Paige says. That’s more than reasonable, considering the long history of white people exploiting black people for non-consensual medical research; in the US, famous examples include taking cells from Henrietta Lacks and secretly enrolling black men in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

23andMe’s research doesn’t take advantage of its participants in the same malicious way. Each 23andMe customer is presented with the choice of whether or not to offer their to pharmaceutical companies or other labs for research purposes, and, according to the company, about 80% of customers opt in. Still, these options aren’t enough to smooth over the distrust between many African American customers and large medical research companies, created by years of abuse in the system.

Even with all this participation, 23andMe’s database isn’t as diverse as it could be. A spokesperson from the company would not confirm the ancestral breakdown of the customers who have taken its DNA test, but acknowledged the underrepresentation of populations in its database. Since 2011, 23andMe has launched a number of programs providing free or heavily subsidized testing for people with non-European ancestry. One initiative, called Roots to the Future, ran from 2011 to 2013 and was conducted with notable research partners including Harvard and Stanford universities. The results (which have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal) found correlations between certain genes in African American populations and conditions like high blood pressure and type II diabetes. The company is in the research-and-analysis stages of a number of other related projects funded by grants from the US National Institutes of Health.

For companies like 23andMe to truly gain the trust of people of color, they need to ensure the research projects they facilitate will actually help communities of color. 23andMe is working on it—the company partners with researchers who are members of the populations it would like to get more data on, for example. But given the centuries of trauma some of these communities have been put through, it will take years to build a working relationship.

Kittle and Paige understood this issue of trust from the start. When they founded African Ancestry, they did so with the appreciation that they could make the community feel more comfortable if they guaranteed to not store individuals’ information.

That decision has a downside, however: it makes it much harder for people to find long-lost family members on African Ancestry than it would be if they used other, more open databases.

Finding biological relatives through genetic testing is a little bit like winning a raffle. In order to find each other, both family members must have taken a DTC genetic test, and their results need to be stored in the same place, whether that’s in a testing-company’s database or on a third-party site like GEDMatch. Larger companies like FamilyTreeDNA, AncestryDNA, and 23andMe often offer customers a better shot because they cast a larger net. For adoptees with few clues about their family history, testing with these companies may be the best option.

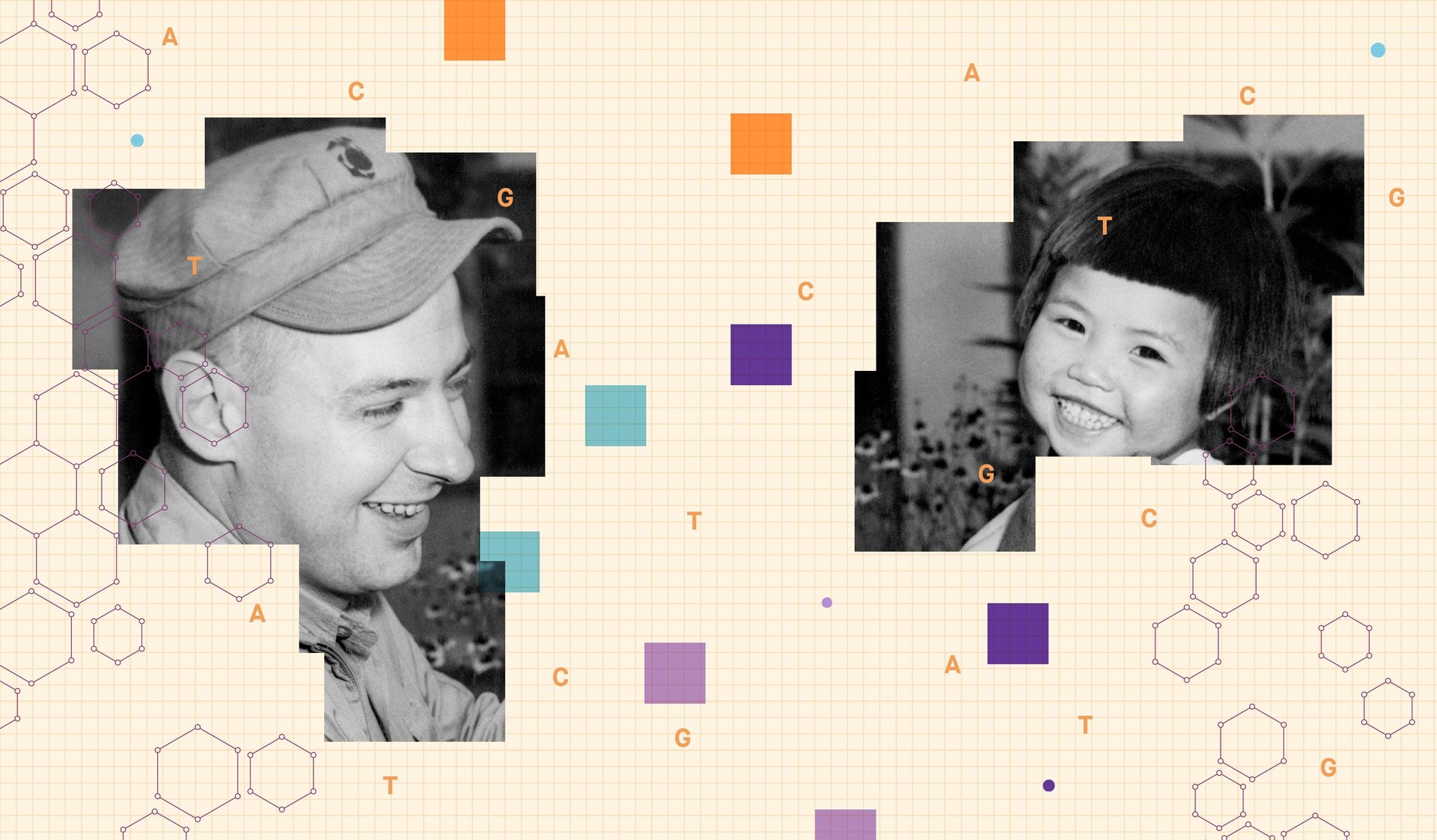

On the other hand, if you do know something about your family tree, it can be much more useful to work with a group that has more specific cultural knowledge. Consider the Korean-Americans, now in their 60s or 70s, who were adopted by American parents in the wake of the Korean War.

After World War II, the Allies divided Korea into two halves, the north, which was “administered” by Russia, and the south, which was “administered” by the US. In 1950, fighting between the two halves broke out. The US military, thinking it would be a short-term operation, didn’t bother building long-term communities for troops to live in. “It was soldiers living out of barracks,” says Yuri Doolan, a historian of US-Korea relations. “Commanders were not encouraging servicemen to create long relationships with Korean women.”

But the Korean War waged for over three years, and during that time, it was common for US soldiers to have relationships with Korean women. US military commanders dissuaded them from getting married, because the occupation was considered temporary.

The war never officially ended (it still hasn’t), though active aggression cooled off in the mid-to-late-1950s. Aid workers sent in to South Korea by the United Nations in those years were captivated by the Korean-American children they found there. Many were being raised by single Korean mothers, but some had been orphaned due to societal stigma against mixed-raced, fatherless children.

In the US, activists petitioned and convinced Congress to change immigration laws so it’d be easier for US citizens to adopt Korean-American children. In 1961, permanent international adoption laws were finally established in the US. These laws paved the way for US citizens to adopt children from several countries, but the focus was South Korea at first. Some estimates suggest that since the Korean War, globally some 200,000 US children have been adopted from South Korea. These include some of the oldest adoptees living in the US, who may have been adopted before formal laws ensured they had paperwork documenting the process.

Bella Siegal-Dalton is an adoptee who eventually went on to co-found an organization to help others like her who struggled to find their birth families. She was born in South Korea in 1961, and, five years later, was adopted by a couple living in Berkeley, California. Growing up, she assumed her American father had served his tour in Korea, had an affair with her Korean mother, and went back to the US without knowing that she was pregnant. For most of Siegal-Dalton’s life, she thought it wasn’t worth the effort to seek out her father. When she was diagnosed with a genetic kidney disorder in 2012, though, she changed her mind. If she could find her birth father, she thought, maybe she could get a better idea of her prognosis.

It took three years and testing with three companies (AncestryDNA, 23andMe, and FamilyTreeDNA) but in 2015, Siegal-Dalton finally tracked down one of her father’s sisters—her aunt—who was living in Kentucky at the time. She reached out, and three days later, got a call back at work. A man named Chris told her, in a southern accent, that he was her cousin. She forgot about the kidney disease. “I didn’t even care about my health at the moment,” she says. “I had a family.”

There was more: her newly discovered family told her that her biological father, Irvin Rogers, had passed away. But, more importantly, they also told her that Rogers had always known Bella existed. “My narrative that I had been given by the adoption agency was not the same that he told his family,” she says.

Here’s Rogers’ family story: Siegal-Dalton’s biological father, Irvin Rogers, was indeed a US soldier. And he had indeed developed a relationship with a South Korean woman, Lee Cheung Hee, during the war. When the US Army told Rogers it was time for him to go back to the States, he initially petitioned to stay, because Lee was pregnant. When the army refused his requests, he went AWOL looking for her.

Rogers couldn’t find Lee, but he did find Lee’s parents, who told him that Lee—and her unborn baby—had died in childbirth. At first, Lee’s parents said Lee and her unborn son were buried in the cemetery near their hometown of Dongducheon; when Rogers couldn’t find their tombstones, Lee’s parents told him they had thrown the bodies into the ocean to dissuade Rogers from trying to contact them further.

Within the year, Rogers returned to the US and started another family. Rogers’s war stories, of meeting Lee and fathering Lee’s child, became an unspoken truth in the Rogers family. Rogers’s sister, Sophie, found a picture of Lee that he’d brought home. Rogers’s other sister Kathy overheard him telling their father about Lee. When Kathy took care of Rogers in his final days, he told her that, in the future, a Korean-American person might contact them looking for biological relatives. He left strict instructions that they should welcome this person into the family.

In September 2015, just two weeks after becoming aware of her American family, Siegal-Dalton was attending a conference in Berkeley, California, at which she had been asked to talk about the relationship between GIs and Koreans. In room number 325 of the Shattuck Hotel, she and some of her fellow conference attendees decided to create an organization specifically dedicated to helping Korean-American adoptees find their birth parents. A month later, their non-profit was official. They called it “325Kamra”: “325” for the room number in which it was founded, and “Kamra” for “Korean American.”

Today, 325Kamra provides free DNA testing—usually through FamilyTreeDNA—for Korean-American adoptees, anyone of Korean descent (usually in the US), members of the US military who served in Korea, and the families of military members who served in Korea. If it identifies a potential match between an adoptee and a potential family member, 325Kamra makes contact on behalf of the adoptee.

It can take a long time because the existing genetic database isn’t that large, and it’s hard to grow that database because the generation of people who were parents during the Korean War is aging. “They still think DNA [testing] means we’ll take blood, or we have to pull a hair out of a toothbrush,” says Tia Legoski, who works with Korean and Korean-American communities to get them to take genetic-ancestry tests.

Giving up a child for adoption, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, was considered shameful in South Korea. Revealing that secret, even decades later, could bring perceived shame to the family, Legoski says. That’s why representatives from 325Kamra work on a case-by-case basis to identify those they think will be the most receptive to hearing about a previously unknown member of the family. Parents may not always be the best choice; sometimes, it may be younger half-siblings.

Who delivers the message also matters. Legoski, who is mixed-race, was born in Korea and moved to the US when she was 15. She speaks Korean, which helps her explain to older generations what 325Kamra does. Crucially, she also understands South Korean culture. “When I call the number, I try to feel for each person,” she says. “Each region in South Korea has a different way of thinking or responding to questions.” Always, she makes clear that the adoptee just wants to make contact, doesn’t necessarily want a relationship, and certainly isn’t after money.

Many people are immediately happy to hear from long-lost biological relatives. But not all, not right away at least.

Cherry is still working on developing a relationship with her biological parents. In the 1980s, they never could have imagined a technology like this, and dealing with new-old family members reopening forgotten wounds isn’t easy.

“Our intention was never to cause pain,” Cherry says. “Our intention was to see who we were.”