In the past four years, we have been repeatedly told that Muslims’ eating habits are anti-Hindu/anti-national as they eat beef; that Muslim men don’t love, they do love-jihad with Hindu girls; that Muslim couples deliberately have sex to increase their community’s population so as to outnumber the Hindus; and that they offer namaz on roads to convert public (read Hindu) lands into mosque territory!

This propaganda is followed by actual violence against Muslims—lynching, molestation, and even rape. Despite this hostile anti-Muslim attitude, Muslim communities do not get involved in any anti-Hindutva counter mobilisation. Muslim religious organisations and pressure groups and even Muslim political leaders (except a few unknown faces who appear on prime-time TV every night!) do not argue for any Muslim mass protest.

It is, therefore, possible to infer that Muslims have decided to remain silent to avoid any confrontation with Hindutva and that they would open their card in 2019. This simple conclusion is problematic. The anxiety called “Muslim silence” must be unravelled for a deeper analysis based on some concrete evidence.

Two counter questions may be asked: (a) Has Muslim political attitude changed, especially with regard to identity-related Muslim issues? (b) Do Muslims think differently from other communities in India?

It is worth noting that the BJP has been using Muslim identity as an “other” to cultivate its Hindutva vote bank. Post-2014 BJP politics marks a decisive shift in this regard.

Unlike the previous NDA government, the Modi-led BJP decided to deliberately demolish Muslim issues in a more direct fashion. Obviously, any radical Muslim reaction would have given the government an opportunity to promote its political image as a truly nationalist establishment.

However, Muslim reactions were very different…the triple talaq issue could not create a Shah Bano–type hype, primarily because there was strong social opposition to this practice among Hanafi Muslims, especially in north India. Even the AIMPLB failed to mobilise Muslim public opinion in its favour. Similarly, the abolition of the Hajj subsidy remained a nonissue, as there has always been a consensus that Hajj travel should be liberalised. Violent cow politics also failed, as eating cow-meat is a highly insignificant matter for Muslim communities in India. That might be the reason why lynching as a preferred mode of violence against individual Muslims has increased in order to keep cow politics alive.

To understand this complex Muslim reaction, we must take the Babri Masjid issue as a relevant example.

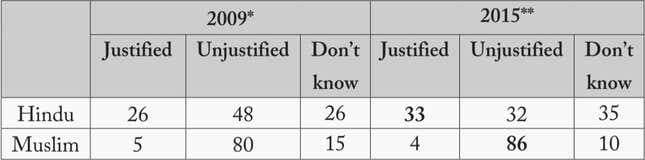

Source: *NES 2009, CSDS-Lokniti Data Unit; **Religious Attitude Survey 2015, CSDS-Lokniti Data Unit

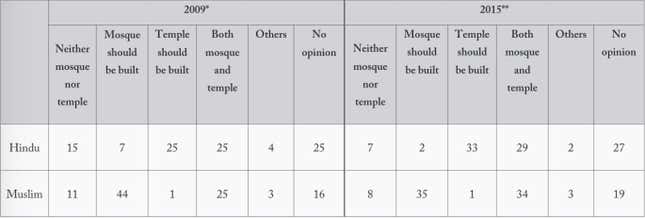

Source: *NES 2009 CSDS-Lokniti Data Unit;**Religious Attitude Survey 2015, CSDS-Lokniti Data Unit

…

To understand the visible calmness of Muslims in contemporary India, we must also have a look at Muslim opinion in relation to what is called national sentiment.

The CSDS-Lokniti’s recent Mood of the Nation survey offers us another set of important findings. The survey finds that the popularity of the BJP-led NDA government is declining. Muslim respondents also share this view. They strongly believe that the Modi government should not be given another chance. This Muslim opposition to the present regime, we must note, does not deviate from the national sentiment as a majority of the respondents (47%) argue that the Modi government is not good for the country.

Similarly, the Muslim response to the present state of affairs is not very different from that of other communities. Muslims seem to assert, more stridently, in fact, that India as a country requires a better government that could provide a positive direction to the nation. The Muslim assertion against the Modi government is also linked to the evolving environment of hate against all marginalised groups in the country.

…

A majority of Indians feel that atrocities committed against the weaker sections of the society are not dealt with adequately by the government. They seem to suggest that the state does not demonstrate a clear attitude against those who create an atmosphere of hate and terror. This is also true about the violence against Muslims. More than half of the respondents asserted that they are not satisfied with the way in which miscreants, such as the gau rakshaks (protectors of cows), are dealt with by the government. These figures also underline the fact that the Muslims of India do share the national view on a few fundamental issues that India faces as a national community of citizens.

At the same time, being the main target of Hindutva politics, Muslims appear to be more concerned and dissatisfied with the present regime. By this logic, the Muslim silence is nothing but a reflection of political indifference, which has emerged as a norm of non-Hindutva politics in the last few years.

…

The possibilities of any “Muslim reaction” must also be seen in relation to the demographic plurality of Indian Muslims… As I argue that the Muslim community consists of a number of diversified Islamic communities, which speak different languages, live in different regions of the country, and even follow varied versions of Islam as a religion.

In the backdrop of this apparent heterogeneity, the idea of having a defined strategy to counter Hindutva seems unreasonable and vague. Muslim silence, on the other hand, points towards the intellectual weakness of the political class. Contemporary BJP Hindutva has failed to produce any constructive and positive programme of action for Muslims as a “community of communities.”

Hindutva survives because of its reactionary position on Islam and Muslims. Non-BJP parties have also failed to articulate any new perspective on Muslims in the absence of old identity-based issues, in which Muslims do not have any interest. To conclude, I make a futurist observation. The political class must realise that Muslim aspirations cannot be reduced to so-called Muslim issues alone.

Muslims, like other socio-religious communities, are more concerned about poverty, employment and education. No doubt, the threat to religious identity affects them psychologically, but the commonly given imaginations of siyasi Muslims do not entirely determine their aspirations as citizens.

Excerpted from Hilal Ahmed’s Siyasi Muslims with permission from Penguin India. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.