China’s financial system is in crisis mode again, and the central bank’s billions aren’t helping

On Dec. 20, as China’s overnight money-market rate surged to 10%—the level reached during the country’s cash crunch last June—the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) pumped a reported 200 billion yuan into the system. That brought rates down to 7%.

On Dec. 20, as China’s overnight money-market rate surged to 10%—the level reached during the country’s cash crunch last June—the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) pumped a reported 200 billion yuan into the system. That brought rates down to 7%.

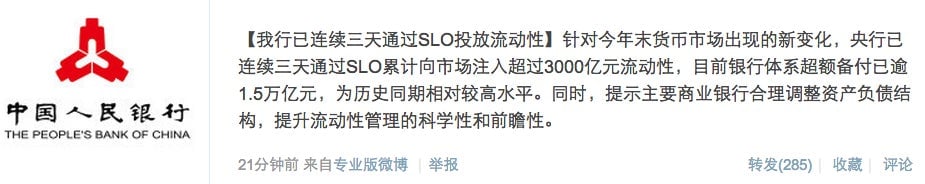

But it wasn’t enough. Rates neared 10% once again today. And the PBOC’s floodgates swung open, again. In total, it injected 300 billion yuan in the last three days via its short-term liquidity operation (SLO), the PBOC said over Sina Weibo (link in Chinese; registration required). Here’s a look at the 7-day rate, via Bloomberg’s Tom Orlik:

What’s causing the money shortage?

It’s due in some part to the fact that the PBOC has halted open market operations since late November in an effort to force companies to pay debts and reduce reliance on the shadow lending system.

Bigger banks are probably fine. ”Traders say that the current unmet credit demand comes largely from small institutions, which are hardest hit by Beijing’s attempt to reduce shadow banking credit,” says Amy Yuan Zhuang of Nordea Markets. Meanwhile, rumors swirled that a joint-stock bank in Hangzhou defaulted on a payment to Citic Bank, according to a note from David Cui of Bank of America/Merrill Lynch.

But there are some unnerving elements to this latest convulsion.

First off, the PBOC’s latest PR strategy has a ring of desperation to it. Shedding its habit of injecting money behind the scenes, the PBOC took to social media to announce SLOs—something it is supposed to reveal only a month after implementation, as the Financial Times points out (paywall). Was it worried about market panic—or just catching up with the times?

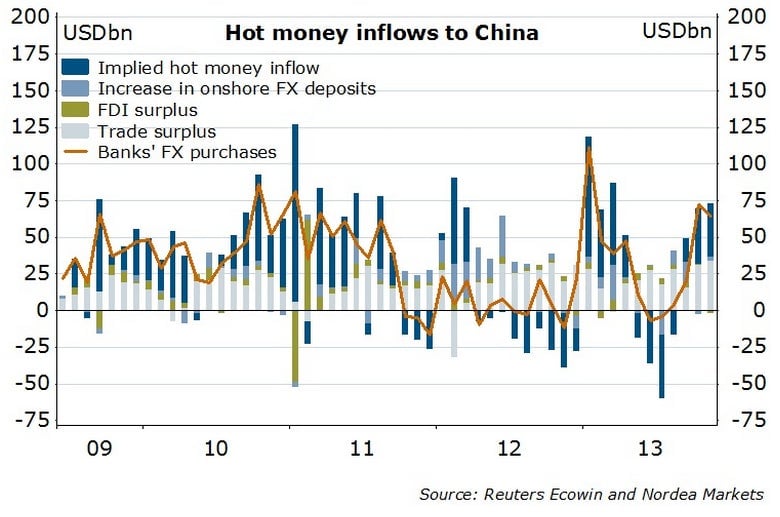

Many liken this episode to the June cash crunch. But there’s a big difference between liquidity conditions then and now. In June, the government had just cracked down on fake trade, which was channelling as much as $50 billion a month into the system, as J-Capital Research estimated earlier this year. In the last few months, however, hot money—as speculative capital is known—has been spilling into China once again.

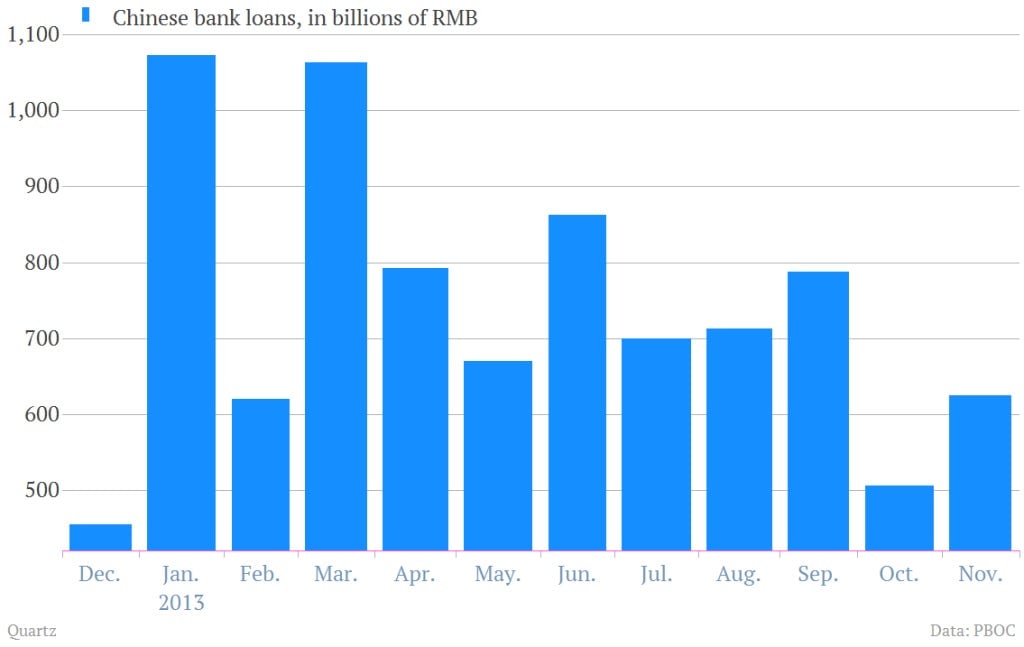

There’s also a lot more credit in the system. China’s on track to have 9 trillion yuan in lending in 2013, the highest level since 2009. Last month, both official and off-balance-sheet lending increased more than expected.

Does this mean a financial crisis is imminent? Probably not. This week’s mayhem is a symptom of withdrawal, as the PBOC tries to wean the system off easy money. As it proceeds, these episodes will only become more frequent. The PBOC’s response today and in June shows that it will do what it takes to prevent things from spiraling out of control. But both episodes also suggest that it’s chronically underestimating the rising amounts of liquidity that “doing what it takes” requires.