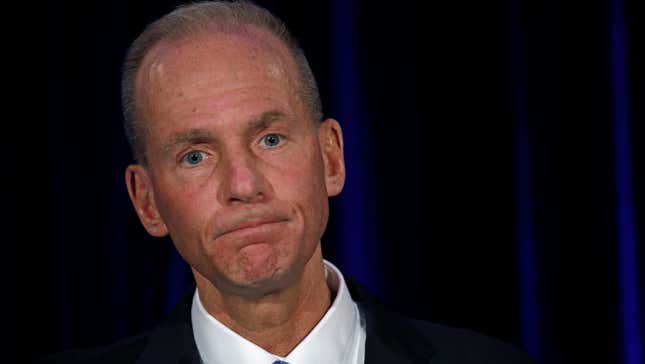

In late April, on Boeing’s first quarterly earnings call after the worldwide 737 Max groundings, an analyst asked an uncharacteristically direct question: “How did this happen?”

It’s a question that many have tried to answer since Ethiopian Air flight 302 crashed in March, just five months after Lion Air flight 610 went down. The crashes killed 346 people, stunned the world, and precipitated a full-blown crisis for one of the US’s most successful companies.

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg responded to the question by invoking a common explanation for aviation disasters. That it was not the result of a single “technical slip or gap,” but rather “a series of events.”

Though the presence (or absence) of a technical gap continues to be fiercely contested, a prominent thesis has emerged since the crashes: The series of events which led to the grounding of one of the world’s most trusted aircraft was precipitated by a broad, top-down pressure. The pressure, of course, was the necessity to keep up with a rival, Airbus, which had edged ahead in the race to maximize the efficiency of the narrow-body passenger jetliner.

The world of commercial-aircraft manufacturing is a duopoly, with Boeing locked in fierce competition with its only global rival, Europe’s Airbus SA. The two companies serve the vast majority of airlines, each owning roughly half of the market. In 2018 the two players’ number of aircraft deliveries—a key indicator for investors—were neck and neck, with Boeing delivering 806 to Airbus’ 800.

And in that duopoly, the A320 and the 737 are two of the most successful aircrafts in history, accounting for nearly half of all commercial airliners. Any competitive edge, however small, could be reasonably be viewed as a mortal threat for the other company. And even if it made little difference to travelers enjoying a golden era of cheap flights, getting left behind was not an option.

Understanding that fierce inter-company competition—in a famously under-competitive industry—goes some way to answering “how did this happen?” But what’s less clear is where we go from here. After all, this powerful duopoly has defined the commercial aviation industry for decades, driving innovation and improving the sector’s safety record to an all-time high.

Sure, it’s possible that Boeing weathers this storm and the status quo is regained once the Max takes to the skies again. However, if the Boeing Max crisis precipitates a more fundamental industry disruption, imagining what comes next is nothing short of existential for the state of modern aviation.

A tale of two giants

If Boeing is fueled by the American belief in capitalist innovation, then Airbus is the quintessential European challenger, based on the tenets of state-owned cooperation and the European project.

Boeing was founded in 1916 by William Boeing, and in the ensuing years served as a pioneer for both military and non-military aircraft. By the time Airbus entered the scene in 1970 as a consortium of companies from Germany and France (and later, Britain and Spain), Boeing was a key provider of military aircraft on both sides of the Atlantic and the leading carrier of passenger traffic.

Airbus set out with the purpose of consolidating European aviation players to provide a meaningful competitor to the Boeing juggernaut.

“Airbus came out of Aérospatiale in the 1970s. It was a French nationalized company,” says Gregory Travis, a pilot, software developer, and writer. “It’s public now, but the incentives and everything else that its executives respond to are quite different from what Boeing’s respond to. Even now. It’s still in its DNA.”

While Airbus managed to make its first sale to a US airline in 1978, the aviation duopoly as we understand it today didn’t really begin until the early aughts, when Airbus finally reached market parity with Boeing, based on aircraft deliveries. From there, the two entered a neck-and-neck battle that hasn’t abated since.

In 2010, the competition reached a fever pitch. Fuel was expensive and jumbo-jets were falling out of favor—so the demand for fuel-efficient aircraft had never been higher. Airbus announced it would re-engine its popular A320 to make the A320neo, resulting in a narrow-body aircraft that would burn 6% less fuel than the 737 model then in the skies.

Just eight months later, after Airbus had sold hundreds of its new A320neos at the Paris Air Show, Boeing announced its answer: It would also re-engine its single-aisle workhorse, giving rise to the 737 Max.

The timing of the move was far from a coincidence. Boeing had debated for years about whether to replace its 737 program with a new aircraft, but now Airbus’ successful rollout had forced its hand. As Airbus’ former head of sales John Leahy told the Seattle Times, “I’m surprised Boeing didn’t see that earlier and start working on the MAX right away as soon as we launched the neo.”

The Max was delivered to its first customer, an Indonesian airline, in May of 2017, nearly a year and a half after the A320neo.

A silent system

In the wake of the crash, much has been written about Boeing’s decision to update an existing air frame, rather than go forward with a “clean sheet,” or building an aircraft from scratch to compete with the A320neo.

Some reports have framed the decision as a kind of cheat or workaround—rather than building a new plane from the ground up, they ostensibly played catch up with an existing aircraft structure, attaching a larger engine. The placement of that larger engine altered the plane’s aerodynamics, which in turn required a software system (the ill-fated Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS), a kind of built-in self correction that would push the plane’s nose down when necessary.

But building airplanes is an incredibly complicated endeavor. Some prominent industry watchers say the idea that updating the 737 was a shortcut is a misunderstanding. Richard Aboulafia, vice president of aerospace consultancy the Teal Group, wrote recently that the 737 Max “was the right product to launch. Boeing was not being greedy, desperate, or short-sighted; rather, there was no business case for a clean-sheet design.”

Samuel Engel, an aviation-industry consultant with ICF, added that Boeing’s decision to re-engine the 737 was in line with years of aircraft development. “If you look back over the history of jet aircraft development, you’ll see that almost every stage, what’s driven the next generation of aircraft is not something fundamental about aircraft structure but rather it’s about the engine technology.”

That the new engine required a software fix wasn’t particularly unusual, either. “It’s not like that’s a new concept,” said Engel. “The Airbus design philosophy has a great deal more electronic and software control than Boeing has typically used, so arguably Boeing was taking a page out of Airbus’ playbook to manage the aircraft’s dynamics using more software.”

So if both players in the duopoly were hewing to a well-established playbook of innovating by updating existing aircraft structure with new engines and software fixes, where did the gravest fault lie?

While it’s true that the “series of events” that Muilenburg alluded to could reasonably include ground crew mistakes, possible pilot error, and the FAA’s overstretched regulatory power, it’s undeniable that MCAS served as the “common thread” for both crashes, Aboulafia told Quartz. Under normal circumstances, MCAS was designed to automatically trim the nose of the plane down if the angle the nose was cutting through the air (its angle of attack, or AOA) was high enough to be approaching a stall.

The problem was that when those AOA sensors malfunctioned and erroneously caused MCAS to push the nose of the plane repeatedly down—as happened in both crashes—pilots were either unaware of MCAS’ existence, as in the Lion Air crash, or unable to counteract it. Pilots from some of Boeing’s most prominent airline partners, such as Southwest Airlines and American Airlines, said they didn’t know about the existence of MCAS until after the Lion Air crash—a fact Southwest’s pilot union called “disturbing.” And according to preliminary black-box readings, Ethiopian Air’s pilots tried carrying out the procedure recommended by Boeing when MCAS erroneously activated to no avail.

However, both Boeing and the FAA maintain it was possible for pilots to override MCAS. The FAA told Quartz that “while Boeing 737 MAX training requirements do not address the MCAS by name, the procedures do include the knowledge to deal with an MCAS event, which is the same as runaway trim. The FAA requires all commercial airline pilots to undergo periodic runaway stabilizer trim training in full-flight simulators.” Still, some pilots have argued that even following the recommended procedure gives pilots little time (possibly as little as 40 seconds, according to New York Times reporting) to counteract MCAS when flying at low altitudes.

The FAA told Quartz that the “737 MAX was certified in accordance with the identical FAA requirements and processes that have governed certification of previous new airplanes and derivatives. The FAA considered the final configuration and operating parameters of MCAS during MAX certification, and concluded that it met all certification and regulatory requirements.”

All of this begs the question: To avoid the confusion, why wouldn’t Boeing have initially been up front about its ingenious software fix?

Travis, whose post-mortem of the crash was widely circulated online, theorizes that explicitly naming MCAS may have required additional training for pilots, and possibly a new type of certificate—which would have effectively said the Max was too different from the prior variant for 737 qualified pilots to fly it without re-training. Either of these would have made the Max a less attractive proposition compared to the A320neo, as minimal additional training was a key selling point. Slowing things down, and thereby making it less competitive, simply wasn’t an option, Travis says.

“They had a mandate coming from on top—this is part of the profitability margin—that whatever you do to ship this thing on time do not do anything that requires additional pilot training because we’ve promised everyone up the whazoo that they won’t have to do any training,” Travis said.

The controversial decision to automatically activate MCAS based on one AOA input—a so-called single point of failure, something aircraft design generally avoids—falls under that explanation, too, according to Travis.

“The second that you introduce a second AOA indicator into the equation, you have to have a procedure that deals with when they don’t agree,” Travis said.

Boeing told Quartz that in the wake of the crashes, they will “be releasing a software update to the MCAS function which will, among other things, use inputs from both AOA sensors to detect and protect against erroneous values, and will alert to the flight crew that the MCAS function is not available for the duration of that flight.”

Room for two

For now, the worldwide fleet of 371 Max aircraft remain grounded, affecting the schedules of more than 50 airlines around the world. On its first quarter earnings call in April, Boeing revealed the worldwide grounding had cost them $1 billion to date.

While that software fix is underway, the company’s reputation—with both airlines and passengers—hangs in the balance. While it may be too early to think about a modern aviation system without Boeing in it, it’s worth pondering if there is a future commercial aerospace industry that isn’t defined by such a powerful duopoly.

Building airplanes, after all, has massive barriers to entry. It’s not as simple as an upstart disruptor taking advantage of a stalwart’s misfortune. In such a fiercely competitive industry, one might assume Airbus would be poised to rise as Boeing languishes. But Aboulafia says the nature of aerospace manufacturing means there isn’t a whole lot of room for Airbus to benefit from Boeing’s misfortune.

“Both sides, Airbus and Boeing, are production constrained. So Airbus’ ability to take advantage of Boeing’s weakness is minor unless this [grounding] is going to last a few years.”

Indeed Engel notes that instead of edging ahead of Boeing, Airbus would be best suited using the crisis as a teachable moment itself. “What’s that saying—there but for the grace of God go I?” said Engel. “If [Airbus is] smart they will look inside just as much as Boeing will.”

Part of the reason commercial aviation enjoys the relatively strong safety record it does, Engel adds, is down to the industry’s tendency to treat accidents as industry-wide learning opportunities, rather than solely competitive advantages. Plus, it’s just not a good look to use a human tragedy to boost your sales. Airbus seems to get that: “Safety is not a competition item,” Airbus CEO Tom Enders was recently quoted as saying.

That said, the fundamentally competitive nature of the industry is not going anywhere. Travis believes there is realistically only room for two players in the game.

“The world really only has space for two manufacturers,” Travis said. “Just the economics of this kind of thing—how expensive it is to make a plane. The world doesn’t want to have just one because it doesn’t want to be held hostage, but it can’t support more than two. So it’s only going to have just two—at least in the aircraft of this size or larger—and the question is who are they?”