Predators with virtually invisible fangs prowl the deep sea

The ocean depths are nearly as mysterious as outer space. Scientists know little about creatures deep in the sea because they have traditionally been tough to reach and difficult to observe. Now, it turns out that being hard to see is key to thriving in the extreme conditions.

The ocean depths are nearly as mysterious as outer space. Scientists know little about creatures deep in the sea because they have traditionally been tough to reach and difficult to observe. Now, it turns out that being hard to see is key to thriving in the extreme conditions.

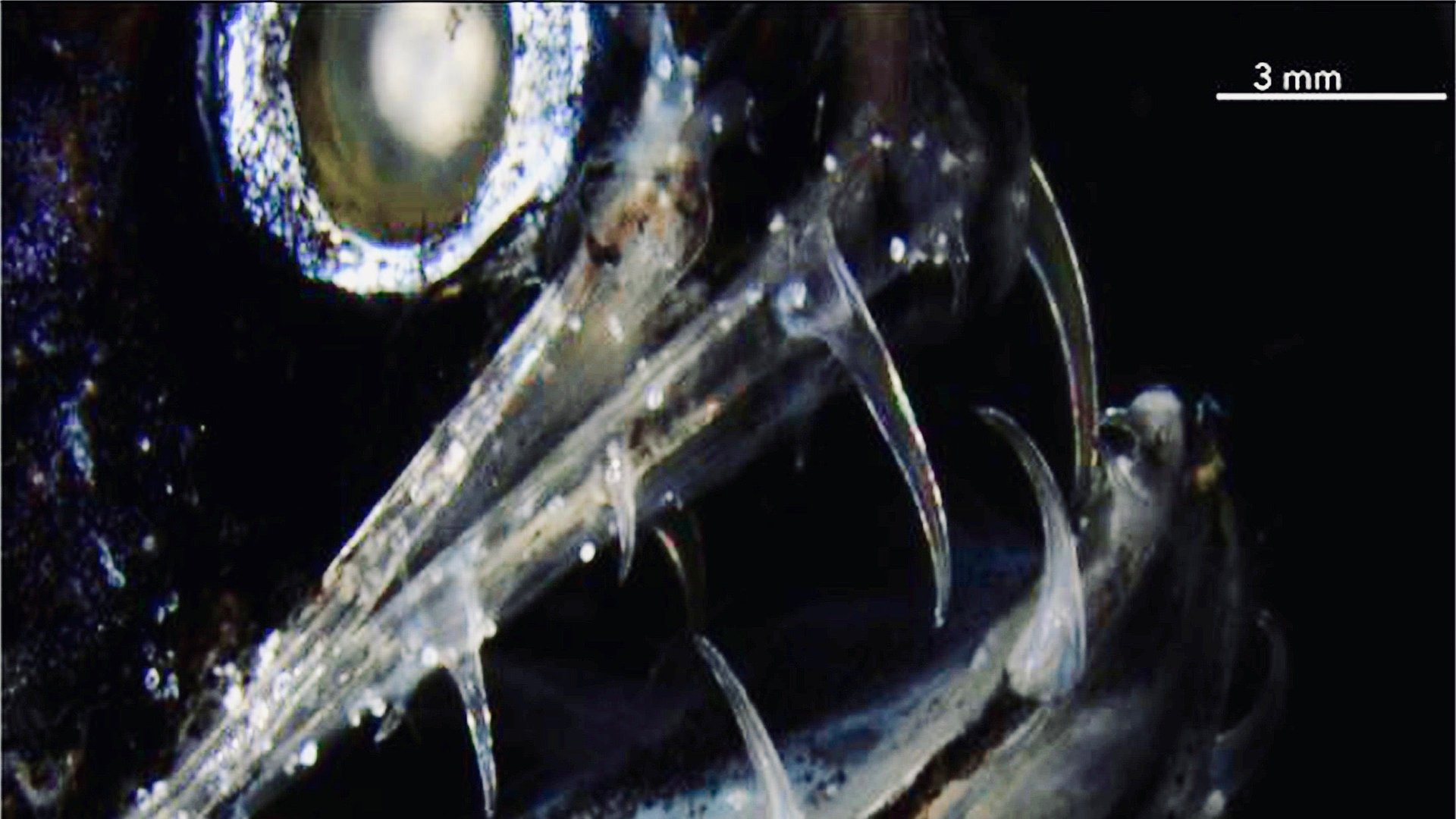

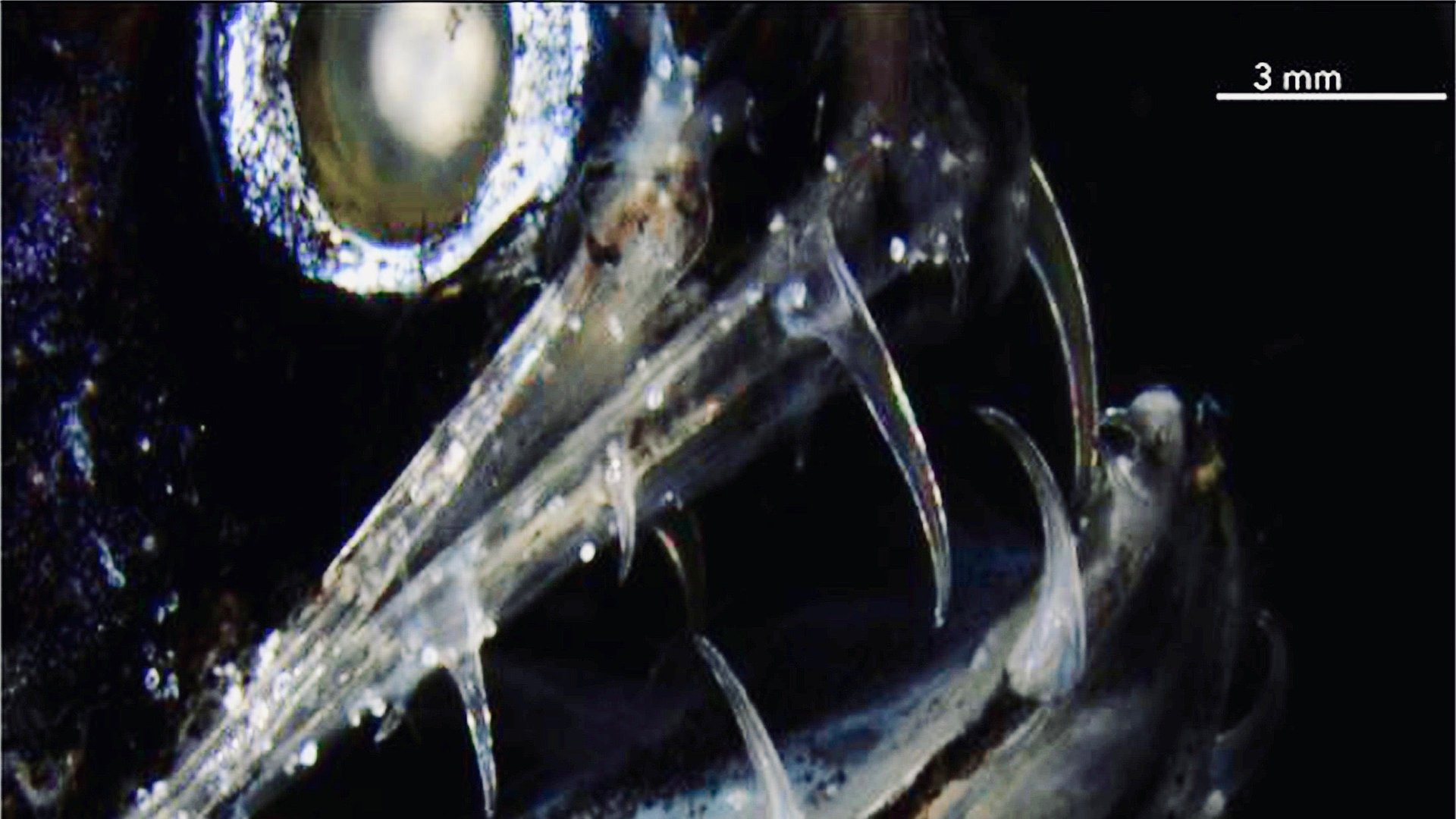

A new study in the journal Matter shines light on the deep-sea dragonfish, which lives in the dark waters of the eastern Pacific and dwells about 4,000 m (13,000 ft) below the surface. The black fish is only a few inches long and looks pretty unassuming to humans. But it’s a voracious predator, and scientists from the University of California, San Diego and the Leibniz Institute for New Materials in Saarbrücken, Germany now think they know why. Aristostomias scinitillans, as it’s known in Latin, is hiding a mighty weapon out in the open.

Dragonfish have a set of sharp, clear teeth that are large relative to their jaws, and that sometimes even stick out. But these teeth, resembling those of sharks or piranhas, are difficult to see because they range from translucent to transparent, depending on the extent of light around them. Thus, these apex predators remain nearly invisible to prey even as they prowl the dark with loose jaws open wide, their tiny sabers poised to chomp on fish up to half their size.

The “transparent dragonfish teeth enable predatory success as it makes its wide-open mouth armed with saber-like teeth effectively disappear, showing no contrast to the surrounding blackness of the fish nor the background darkness of the deep sea,” the researchers write.

Scientists have had difficulty studying “deep-sea effects” on biological materials extensively, but they know that the extreme conditions—lack of ambient light, low temperatures, high pressure in the ocean depths—have led to “fascinating adaptations.” The researchers behind this latest study note that transparent teeth seem to be a feature of deep-sea predators but believe no one has studied the makeup of this denture until now.

In the dragonfish, they found two homogeneous concentric layers, an enamel-like substance and dentin, that make up the wall of the teeth. These are the same materials found in human teeth; however, the sea creature’s denture is structured differently, composed of microscopic minerals arranged in a somewhat haphazard manner that scatters light. The upshot: Environmental light and illumination from bioluminescence don’t reflect off the predator’s teeth.

“We believe that the elaborate structural arrangement of the teeth, which provides mechanical strength combined with transparency, enhances predatory performance of the fish,” the researchers write. These tricky teeth, in combination with the black body invisible to other fish in the ocean dark, make the deep-sea dragonfish a stealthy and effective predator in waters where food is scarce.

Scientists have yet to study the deep-sea dragonfish in its natural environment, so they haven’t observed the sneaky swimmer at work. But the new lab analysis of the materials in the teeth makes it clear that transparency is an essential element of the creature’s success. Analysis of biological materials in other deep-dwelling organisms could yield more secrets of survival in extreme ecological conditions.