A new party wants to break Bosnia’s political deadlock using computer science

A fledgling political movement called Platforma za progres, Bosnian for “Platform for Progress,” is trying to fix Bosnia and Herzegovina’s political deadlock using computer modeling and data analytics, a toolbox that decision-makers around the world are increasingly experimenting with.

A fledgling political movement called Platforma za progres, Bosnian for “Platform for Progress,” is trying to fix Bosnia and Herzegovina’s political deadlock using computer modeling and data analytics, a toolbox that decision-makers around the world are increasingly experimenting with.

Bosnian politics has come to feature high levels of mutual distrust and corruption. In 1995, the Dayton Agreement established peace between Bosniaks, Croats, and Serbs, ending an almost four-year war in which more than 100,000 people died. The treaty created a new, shared political system for the country but also institutionalized Bosnia’s divisions. Since then, the government has been led by a three-person presidency representing each of the main ethnic groups. Major reforms demand their consensus, which can stand in the way of wide-ranging change.

Many political parties have tried to cut this Gordian knot before. But Platforma za progres is looking for solutions using complexity science, a branch of research that harnesses computing technology to try and understand how systems interact, in order to predict social processes and move policy forward.

The issues facing Bosnia and Herzegovina are significant. The country is plagued by persistent fears of ethnic divisions. Its youth unemployment rate is 46.7%, and 5% of the population has left since 2013. Among Platforma za progres’s ideas is using computer modeling to design incentives, like increases to the minimum wage, or reforms to the country’s education system, that would encourage citizens, and especially the young, to stay.

“Think about pilots. They go through so many hours of flight simulations. Policies should go through the same process,” says party leader Mirsad Hadžikadić, a professor and director of the Institute of Complex Systems at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. “’I think’ should not be a category in politics anymore.”

But applying computer science to try solve some of the country’s most persistent and pressing social problems will require answering some ethical and practical questions first.

Politics and programming

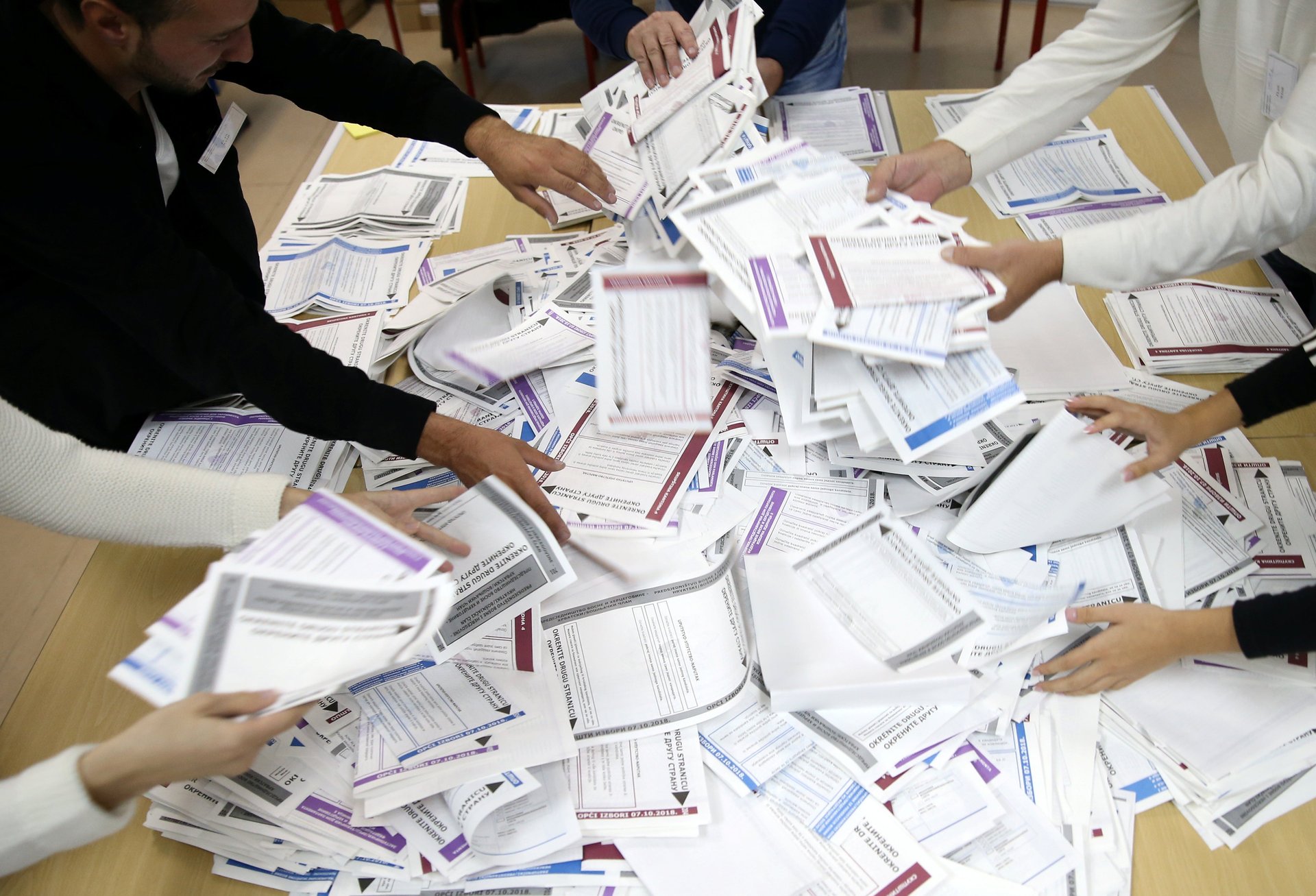

After spending more than 30 years in the US, Hadžikadić returned to Bosnia and Herzegovina, his home country, last year to run in October’s presidential elections. The 64-year-old professor received 10% of the votes from the Bosniak list—about 60,000 ballots. That might not seem much in a country of 3.5 million people. But since elections are split into three lists—Bosniak, Croat and Serb—and each citizen can only vote for one of the lists, it is a surprisingly high result for a first-timer, says Adnan Huskić, a political science professor at the University of Sarajevo.

The primary goal of Platforma za progres as it prepares for the 2020 Bosnian local elections is to rid the country of its institutionalized splits. “The strength of any system lies in the interaction of the people. If you want to control them, you have to split the masses. That’s something that nationalists here have understood perfectly,” Hadžikadić says.

The country’s political system was set up this way to end the war and to guarantee that one ethnic group couldn’t be overruled by another. The system created under the treaty was designed to be temporary, until a more viable system of checks and balances could be installed. But the government has been unable to agree on much-needed institutional reforms.

Shaking up the system isn’t easy. In 2009, the European Court for Human Rights (ECHR) even ruled the country’s constitution discriminatory for not allowing Roma and Jewish candidates to run for the presidency, because they were not one of the three “constituent peoples” permitted to do so. Nothing has changed since then.

Computer simulations to predict social dynamics

One of the main methods Hadžikadić has been working with is agent-based modeling, which involves running computer-simulated interactions between so-called “agents”—units within the simulated space that are equipped with different characteristics and designed to act and interact like humans. Their virtual environments are carefully developed by social scientists, psychologists, and researchers to test potential reactions to change.

Agent-based modeling is like watching fish in a pond. You can see how the fish interact, but also the ripples on the water’s surface created by that interaction, and how those secondary actions affect the environment. Analysts can use these outcomes to ask: Which real-world levers can be used to influence policy toward peace? How do the constituent parts of, say, a city—from infrastructure, to institutions, to people—interact and influence each other?

As an example, the Institute for New Economic Thinking at the University of Oxford and the Bank of England have used agent-based modeling to conduct research on the UK housing market. Outcomes are used by the Bank of England to analyze “what-if scenarios and to predict the most likely effect of possible macro-prudential policies,” the researchers write.

Visualizations like these, underpinned by data, offer insights into the workings of systemic processes and provide a way to predict developments and guide policies towards beneficial outcomes. Such models start at a micro-level, reflecting the individuals that make up a system. The behavior of every “agent” counts.

Elizabeth von Briesen, one of Hadžikadić’s PhD students at UNC Charlotte, is looking at the dynamics of genocide in attempt to better anticipate the social pressures that lead to such disastrous outcomes. With agent-based modeling, “we can turn different characteristics on and off, map emotions and rising tensions, and monitor population size change. What we do is look for thresholds that make peace more likely,” von Briesen says.

Stefan Thurner, president of the Complexity Science Hub Vienna, a pioneering research institution using complexity science to tackle issues from climate change to urbanization to energy, believes this type of modeling will be ever-more commonly used by the world’s decision makers. “It is very likely that in the not-so-distant future, all political decisions will at least in some way be supported by agent- based modeling,” Thurner says.

Patterns in data

Platforma za progres believes that it can use computer science to get people to participate in the political discourse and improve the conditions around them, instead of just accepting them. But how can it move beyond computer applications and theory to tackle Bosnia’s real-world problems to this end?

One focus of Platforma za progres is education reform. They are designing a computed model of the education system guided by questions such as: How can technology change education? How much should education cost, and how do we measure its success? How should we encourage and enable creativity? Finding answers to these questions first will be crucial to finding lasting solutions, the party is convinced.

The party is also looking to compute what the best and most achievable minimum wage for the country should be, as well as propose salary levels for the labor market.

Roughly 80% of Platforma za progres’ nearly 4,000 members were born after 1985, according to the party, and 17% of its members are 23 or younger. Successfully reforming education and increasing wages could help change the minds of the more than half of young people who have expressed a desire in recent years to leave.

Zorana Tovilović, a 22-year-old medical student and party supporter, believes these approaches could be the “spark” for much-needed change. “Things are not so bad here for those who take the future in their own hands and don’t just wait for the country to solve their problems. What we need is quality education so we can create our own opportunities.”

Huskić believes that the only way the new movement can be successful is to focus on everyday problems affecting people. “There is no shortage of good ideas in this country, but our system is a struggle for all of them,” he says.

Data danger

First, the party needs data.

Hadžikadić is working on putting together an analytics team that will work with local universities to produce, collect, and purchase data—similar to what polling institutions use— to analyze social processes in the country to inform policies.

In addition to agent-based modeling, this office will rely on statistics and machine learning. Artificial intelligence will be used to understand patterns of behavior and detect regularities within the data, Hadžikadić explains. The analytics team hopes to deliver detailed insights about other issues in Bosnian society, like the unstable economy, nationalistic upheavals, the declining population, and the high degree of corruption.

“Right now, we are falling blindfolded. We have to get to a point where I can say that A will lead to B at a given probability,” he says.

However, the collection of data to predict social processes has the potential to be dangerous, especially given the opaque way it has been used in other elections across the world. When computing such systems, there are hundreds, sometimes thousands of decisions to be made, Thurner explains. If one of them is wrong, the outcome might be completely misleading. So the results have to be considered with great caution.

“At the same time, the most dangerous model will be the one that is flawless—it can easily by misused,” Thurner adds. Caution is imperative.

To improve the applicability of their models, researchers try to replace all assumptions with sound data—an approach Platforma za progres says it is following.

Hadžikadić says his party is only working with a small number of selected analysts, encrypting data to shield against intrusion, and using it to only answer specific questions. Given the degree to which data have been misused by companies and governments everywhere, addressing critics’ skepticism might need to be part of the process as well.

Hadžikadić is convinced that thorough data analysis and computed modeling will offer new solutions to solve political chaos. To gain influence in the country’s politics, the party is now hunting for candidates to run in the 2020 local elections. This will be the next big test for the movement, which will try to reach 300,000 votes across the country.

“Bosnia is an example for a worldwide trend,” he says. “It’s a very diverse country, where different religions and ethnicities live together. We have to learn to benefit from this diversity.”