Why you think your dog loves you

Of course your dog is good. All you have to do is look at its expressive canine face to know it. Now, a new scientific study suggests that as humans were domesticating dogs, the animals evolved certain facial muscles in order to generate precisely this adoration.

Of course your dog is good. All you have to do is look at its expressive canine face to know it. Now, a new scientific study suggests that as humans were domesticating dogs, the animals evolved certain facial muscles in order to generate precisely this adoration.

The research, published on June 17 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by scientists from the UK and US, focused on anatomy and behavior. Examining the distinctions between facial muscles in dogs and wolves and the different expressions they show on their faces, the researchers conclude that “domestication transformed the facial muscle anatomy of dogs specifically for facial communication with humans.”

Your good dog vs. the wolves

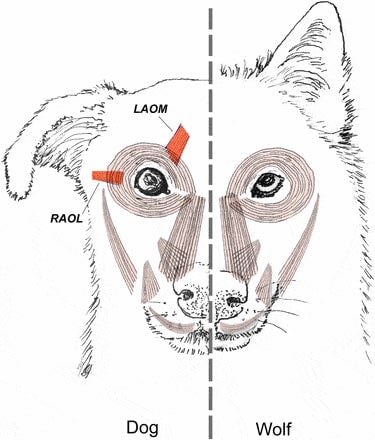

The findings are based on dissections of wolves and dogs, which show few differences except around the eyes. Two kinds of eye muscles are prominent in many dogs but not developed in wolves. The researchers also compared facial expressions that both types of creatures (although not of the same breeds) in animal shelters and wolf parks, finding dogs were much more inclined to make cute faces.

The team argues that dogs evolved muscles that allow for more pronounced facial expressions over thousands of years of domestication because these looks generate a nurturing feeling in humans. Prior work shows that dogs and humans experience a mutual rush of oxytocin—a hormone that plays a role in social bonding—when they gaze at each other. There also is evidence that dogs are more inclined to make eye contact than wolves, and data shows humans are moved by infant-like canine features, known as paedomorphism.

How dogs raise eyebrows

A muscle responsible for raising the inner eyebrow intensely is uniformly present in dogs and not in wolves. Dogs also move their brows significantly more often and intensely than wolves. “That facial shift increases paedomorphism and resembles an expression humans produce when sad, so its production in dogs may trigger a nurturing response,” the researchers write. “We hypothesize that dogs’ expressive eyebrows are the result of selection based on humans’ preferences.”

Dissections showed that domestic dogs and wolves had relatively uniform facial musculature, except around the eyes. There, two types of muscles varied between the two creatures. The levator anguli oculi medialis muscle (LAOM) was present in dogs, whereas the gray wolves had only “scant muscle fibers surrounded by a high quantity of connective tissue.” As a result, wolves can’t raise the inner corner of their brows like dogs and that raised brow is how dogs make faces that remind us of infants.

Similarly, the retractor anguli oculi lateralis muscle (RAOL) is developed in all dogs but Siberian huskies, who are more closely related to wolves than other breeds. The RAOL was merely fibrous in wolves, not a developed muscle.

The researchers believe that human interaction with canines created “selection pressures on the facial muscle anatomy in dogs strong enough for additional muscles to evolve.” The hypothesis is interesting, but it is just a theory. They suggest that future research should explore developments in more dog breeds and other domesticated species like cats and horses.