Facebook created our culture of echo chambers—and it killed the one thing that could fix it

This week Jürgen Habermas, one of the world’s most famous living philosophers, turned 90. A week before, Congress hosted yet another hearing investigating tech platforms Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple.

This week Jürgen Habermas, one of the world’s most famous living philosophers, turned 90. A week before, Congress hosted yet another hearing investigating tech platforms Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple.

What does one event have to do with the other?

In 2006, long before social media echo chambers were a worldwide phenomenon, Habermas warned that “the rise of millions of fragmented chat rooms across the world” would lead to “a huge number of isolated issue publics”—micro public spheres that threaten the shared national conversations that are essential to democracy.

Habermas’s philosophies and the antitrust investigations both point to a fundamental issue we face today: the concept of a public sphere, and what tech companies and the government can and should do to protect democracy.

Facebook, like Twitter and Google, represents the modern version of the public sphere that Habermas and other democracy theorists have called for. With more of our lives lived online, we’ve stopped prioritizing physical spaces, and therefore lost shared spaces spaces for public discourse.

The internet has largely satisfied a human desire for connection, but it doesn’t necessarily cultivate a democratic exchange of information.

Democratic discourse depends on a shared understanding of what matters, what the facts are, and which sources and speakers are reliable.

Trend setting

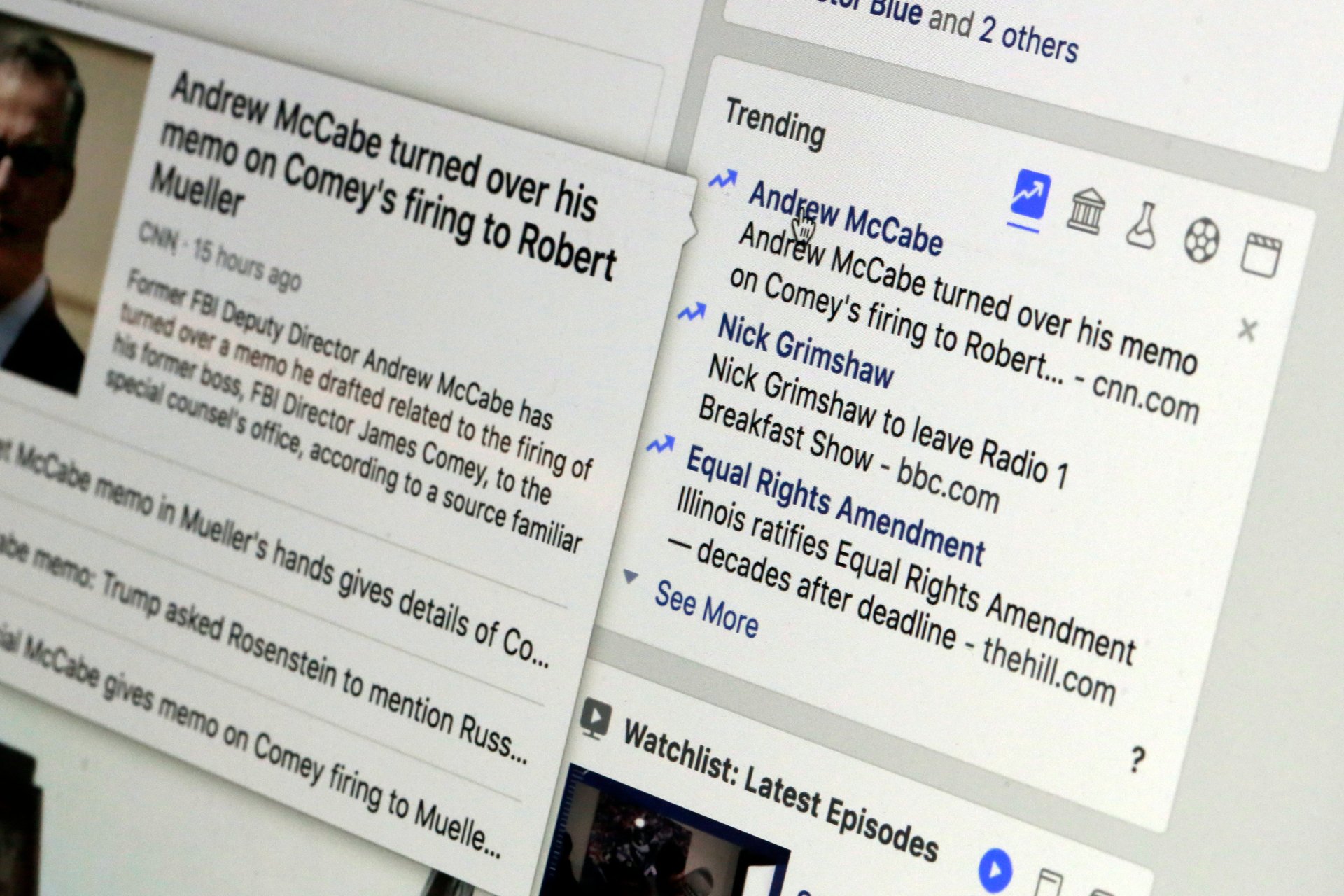

Before its untimely dismissal, Facebook’s “Trending” feature lived in the small white box on the upper right-hand corner of your home page, allegedly listing the news stories most widely shared and discussed across Facebook’s ecosystem.

Although problematic in its application, this tool had the potential for an entirely citizen-driven solution to an age-old problem of the public sphere: determining what issues deserve our attention, and how much of it.

Features like Trending in theory help support and maintain the social media space as a venue for public conversation in democratic discourse—if platforms can stick to implementing them the way they were initially advertised.

Every day in newsrooms around the world, editors decide what is newsworthy, using their judgment to determine what we end up reading, hearing, and seeing.

Traditional media sources have struggled with this problem for centuries: What, exactly, is newsworthy? What do people actually care about? Social media is now a strong indicator in those decisions.

Trending, similar to features on Twitter, Google News, and other platforms, was presumably designed as a tool to automate this minefield of a process, capturing trends at a broad scale and thus offering a picture of what citizens themselves consider to be their most pressing concerns and interests.

With data from a monthly active user pool of 2.38 billion people worldwide, Facebook’s Trending tool can still help answer those questions, by directly capturing the common interests of the public without editorial filters. It just needs to be fixed.

Trending troubles

Trending as a concept is an antithesis to our current echo-chamber media landscape, in which users are primarily shown news that is algorithmically tailored to their interests.

This sort of customized news access has led to increased political and social division.

When you only see news that already confirms (echoes) your biases, you lose the opportunity to engage thoughtfully with new or opposing ideas. Society misses out on opportunities to grow, evolve and innovate.

In this hyper-personalized public sphere, citizens are bound to develop a skewed understanding of reality, by, say, becoming fixated on yet another social media feud while a wildfire rages in the next town over.

In the early pages of his 1989 book The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, Habermas discussed “the public sphere as a realm of freedom and permanence” in reference to Greek philosophy.

“In the discussion among citizens issues were made topical and took shape,” he wrote. It “provided an open field for honorable distinction: citizens indeed interacted as equals with equals, but each did his best to excel.”

Habermas also observed that “publicity has changed its meaning” with developments in mass media at the time: “Originally a function of public opinion, it has become an attribute of whatever attracts public opinion.”

Yet if Facebook Trending functioned as prescribed, it would allow for a discursive landscape without the limits of individually imposed echo chambers. It would give us an unfiltered picture of a public discussion across a major social platform, and a way to understand what is important to the larger public, not just our own interest groups.

The tool promised to rebuild a common understanding of what matters to the public. In the end, it was not properly designed and failed to function as a way to gauge what’s in the zeitgeist.

It was criticized for being easily manipulated, a ready tool for corporate gaming and political disinformation campaigns.

It was fairly simple to control the lists by using automated bots. Some argued that Facebook was too slow in moderating harmful content, such as conspiracy theories, which appeared in Trending news. Many derided the algorithms powering it as biased or faulty.

But algorithms are neither good nor bad: They are what we program them to be. Algorithmic bias is merely a reflection of systemic bias, as filtered through designers and engineers.

Facebook, (along with the other major tech companies like Twitter and Google), can fix these algorithms. It can improve moderation functions of the feature, for example by instituting greater lags before news topics hit the list.

It desperately needs to reform its controversial moderator system by introducing better employee support, protection and oversight, improving internal and external guidelines, and flagging controversial topics and news sources, to start.

Facebook and other social platforms should also allow for more research and academic access to its data, such as information on how to effectively—and ethically—engage people with news stories.

Trending was an imperfect tool, but it held the potential to capture public conversations and common concerns—as well as important disputes—at a scale that wasn’t technologically possible before. It has been difficult to replicate since.

The capacity of any public sphere is limited—both by the space that media allots to news, and by the amount of collective attention the public can grant to any particular topic. It is crucial that we do everything we can to protect democratic discourse and support the development of an open, civil, digital public sphere.

Tech platforms like Facebook hold a tremendous power to help facilitate this. With the role they occupy in society, and increasingly in government, they also have a responsibility to do so.

On the government level, we need to rethink particularly restrictive takedown requirements, such as Germany’s NetzDG law. We need policy that protects intermediary liability safe harbors, like America’s increasingly threatened CDA Section 230. We need laws that support net neutrality and open internet access worldwide.

From a 2019 vantage point, one might be tempted to conclude that Habermas’s 2006 prediction has been fully vindicated, and that digital discourse was bound to lead to the erosion of shared public conversations, based on his assessment of the “parasitical role of online communication” in the public discourse.

But the future of the public sphere is not engraved in stone.

Since social media platforms now control such a vast part of our infrastructure for public conversation, they have tremendous power to shape it. The removal—rather than repairing—of features like Trending is but one example of how consequential reactive decisions impact our public spheres.

To protect democracy around the world, social media platforms must live up to their responsibility and work harder to create better environments for constructive democratic discussion.