“Bodies and minds are breaking down”: Inside US border agency’s suicide crisis

Mental health issues are plaguing the ranks of US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), as officers deal with increasing job stress related to the crisis at the southern border and lingering financial problems caused by the partial government shutdown.

Mental health issues are plaguing the ranks of US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), as officers deal with increasing job stress related to the crisis at the southern border and lingering financial problems caused by the partial government shutdown.

In May, CBP asked for an additional $2.1 million for the agency’s Employee Assistance Program (EAP), which provides counseling and other help to workers facing personal or job-related issues. The additional money was needed, CBP wrote in a funding request obtained by Quartz, to respond to the “health and safety of its workforce.”

“EAP use…increased in response to unanticipated critical incidents and other emerging crises, such as the unexpected response required for migrant caravans, employee suicides, and the need for a financial wellness program after the extended partial federal government shutdown,” CBP wrote in the filing. “The unanticipated and unprecedented situation at the southern border over the past 12 months resulted in a significant increase in EAP activity and it is expected to continue while the migrant crisis is ongoing.”

Current and former CBP officers, union leaders, and internal CBP documents all describe an agency that is overburdened and understaffed, struggling to keep up with the growing crisis sparked by the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration. To handle the rush of detentions, the agency now requires mandatory overtime and forced job relocation to bolster its ranks. This added pressure, coupled with the usual strain of working border security and dealing with often desperate families seeking asylum—many of whom face indefinite detention as they await overloaded court systems—is wearing down the force.

According to its own records, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), CBP’s parent agency, has known about this issue for years. But its efforts to address the problem have been intermittent and neglected. And according to at least one expert, agency supervisors have in fact actively discouraged officers from seeking the help they need.

While the emotional stress affecting CBP officers can’t compare to the suffering of the tens of thousands of migrants they detain, the same government policies are at the heart of both problems.

“My continuing thought has been that this level of activity combined with the disastrous policy of wholesale separating children from parents has a very negative impact on CBP personnel. They did not join to take a 2-year-old from his mother,” former CBP commissioner Gil Kerlikowske told Quartz.

For three straight years, law enforcement suicides in the United States have surpassed line of duty deaths. At CBP, one of the largest law enforcement agencies in the country, more than 100 employees died by suicide between 2007 and 2018, according to the agency itself. Morale among CBP officers ranks among the lowest of all federal agencies.

Tony Reardon, the president of the National Treasury Employees Union, which represents CBP officers, confirmed that stress at the agency is higher than it has been in the past. The force is overworked, he said, and the migrant crisis has changed the nature of the job.

“You have human beings, their bodies and their minds, breaking down,” Reardon said.

Vincent Salgado, a CBP officer at the Calexico border crossing in California, said the excessive overtime is exhausting. “The morale is down,” he told Quartz. While he doesn’t personally know anyone at CBP who has died by suicide, Salgado said he’s aware that it’s a problem. “Suicides have been ongoing.”

When a CBP officer takes their own life, word typically reaches Reardon through the union’s local chapter staff, who sometimes helps grieving families navigate the life insurance process. “I’ve gotten the phone calls. It’s heartbreaking when you hear about someone who is not able to cope, and who ends up leaving their family,” Reardon said.

He doesn’t have access to data about how many officers have died by suicide recently, but he said he noticed an unsettling uptick in those phone calls, beginning about two years ago. “It started to look like, whoa, there’s a problem here.”

He’s spoken with CBP officials about the need to more urgently address the issue. “I know they’re trying to deal with it. I’m continuing to talk to them about trying to get even more done.”

The union also represents employees of 32 other US federal agencies. “I’m sure that there are people who commit suicide in other agencies,” Reardon said, but “the only suicides I’ve been made aware of are those at CBP.”

Overworked

A nationwide and ongoing CBP officer shortage means that virtually everyone at the agency is working mandatory double shifts that add up to 16-hour days. Salgado said he works double shifts two to three times a week.

“It means less time at home. You don’t have the opportunity to see family members, or attend special outings,” he said.

What’s worse, managers often tell officers they have to work a double shift with very little notice, often on the same day. And refusing is not an option. “It’s a requirement of the job,” Salgado said.

Understaffed ports also means more work per person every shift.

“If it’s not the overtime, it’s the workload,” Salgado said. “Everything works hand in hand. The overtime pushes them to exhaustion, especially if they’re having to do it two or three days in a row. And it’s not just exhaustion, it’s their family life.”

At the same time, some officers are still struggling to regain their footing after the 35-day partial government shutdown that straddled 2018 and 2019. Many officers were required to work without pay for two pay periods in a row. This is no small thing when roughly 78% of US workers live paycheck to paycheck.

“They had to deal with all the stressors that come from those situations. Can’t pay your mortgage, can’t pay your rent, cause you don’t have any money,” Reardon said. “Many of them are still trying to catch up.”

Understaffed

CBP has long struggled to both find and retain officers. The time-to-hire for a CBP officer, from the recruitment to job offer, takes an average of 300 days. Its staffing shortfall now, according to the union that represents its employees, is 3,700 officers.

And due to the crisis at the southern border, the workload is rising, requiring the agency to accomplish more with fewer people. At locations along the southern border, the conditions are a particularly hard sell. Many officers live in remote, lonely towns, and work in 120-degree heat.

As CBP official Benjamine “Carry” Huffman and Border Patrol sector chief Rodolfo Karisch put it in testimony to Congress in March:

“One example of a hard-to-fill location is Lukeville, Arizona. Although many of our Arizona border locations are remote and hard-to-fill, Lukeville is particularly challenging. It is an isolated outpost along the Mexican border, in a community of fewer than 50 people. It has one small grocery store and gas station. The closest school and medical clinic is 39 miles away in Ajo, Arizona. The nearest metropolitan area—Phoenix—is 150 miles away. The climate is especially harsh; in the summer, many of the local roads are impassable because of monsoons. Furthermore, the groundwater in Lukeville requires significant treatment to make it potable, due to traces of arsenic.”

At the same hearing, the two said the harsh conditions make officers “reluctant to encourage their family members or friends to seek employment with CBP.”

But the agency desperately needs bodies. Between 2015 and 2016, CBP “nearly tripled” its recruiting events across the country, according to a USA Today investigation, showing up at “country music concerts, NASCAR races and Professional Bull Riders events to find applicants.”

In 2017, US president Donald Trump signed an executive order demanding CBP hire 15,000 more personnel, 10,000 more CBP officers and 5,000 more Border Patrol agents. In 2018, CBP only managed to hire 368 CBP officers and 118 Border Patrol agents. An extensive application, involving a polygraph test that more than 40% of applicants fail, makes the hiring process extremely slow.

To hire those 5,000 Border Patrol agents alone, the Department of Homeland Security Inspector General estimated that the agency would have to screen 750,000 applicants.

To help relieve these staff shortages on the southern border, CBP has begun reassigning officers from other ports of entry. There are 328 locations in the United States where migrants can legally cross and that are staffed by CBP officers, and most of them are nothing like the southern border. Many are relatively sleepy, like some of the smaller ports on the Great Lakes along the border with Canada.

These temporary new assignments used to be voluntary, but because there are so few willing to go, the agency has begun “drafting” people, requiring them to make the move.

These drafted officers are given three or four days notice to get on a plane and head south, Reardon said. “Most people have families. You can’t give them a month’s notice?” Reardon asked when he testified to Congress in March. The involuntary overtime and involuntary reassignments, he said, “disrupts” families and “destroys morale.”

The draft policy, which began in 2015 but has intensified under Trump, means that an officer from, say, a quiet port on the border with Canada could suddenly find themselves in the crushing heat of southern Texas, working double shifts in packed migrant detention centers. Known as “Operation Southern Support,” the policy also leaves ports of entry in other parts of the county understaffed, increasing the workload on the coworkers left behind.

“You can’t just say, ‘My child is in a school play today,’” Reardon said. “It doesn’t matter. You’re working.”

Strains of the job

Reardon recently visited the Fort Brown CBP facility in Brownsville, Texas, where he said he found officers preparing ham sandwiches for migrant detainees.

“These are highly trained people slapping sandwiches together,” he said.

While Reardon said it’s not unusual for CBP officers to deal with detained migrants, the current circumstances are extreme.

Reardon also recently went to the Ursula Central Processing Center in McAllen, Texas, where he said 2,700 migrants were being held. “In these detention centers you’ve got a lot of influenza, chicken pox, mumps, scabies,” he said. The officers tried to keep the facility clean, he said, but detaining large numbers of ill people in one space made that difficult. The conditions were bleak. “Candidly I would give you my perspective: It was heartbreaking to see sick children in there.”

CBP officers who work all day in these enclosed environments, or transport sick people in vans, are always on edge about getting sick themselves. “They’re very concerned about contracting these illnesses. That’s a big deal. That’s stressful in and of itself,” Reardon said.

Even without the added pressures created by Trump’s crackdown, the job has long been emotionally draining. CBP agriculture specialists, for example, are responsible for making sure any package entering the United States is contaminant-free—an error in judgement could result in a public health crisis or a new invasive species taking hold in the country. Officers who patrol vehicle crossings, in another example, never know who is behind the wheel. Last month an American citizen sped his truck through a border crossing at San Ysidro, San Diego—the busiest official land border crossing in the world. Another vehicle blocked the truck, and when CBP officers approached, the driver opened fire. The officers shot back, killing him. Two Chinese nationals were found in the back of the truck. The incident rattled officers staffing vehicle crossings across the region.

“The officers are out there with this at the back of their mind,” Salgado said.

Help is hard to come by

The US government is aware of the increased pressure on CBP officers, and the resulting rise in demand for mental health support. But by its own admission, it has failed to do much about it.

In 2009, long before the current crisis at the border, DHS created a program called “DHSTogether.” Its mission was to build “resiliency and wellness capacity” at the department. But the committee responsible for the effort only held its first meeting years later. “Although the program had been in existence for almost 4 years…it did not yet have a formal vision or set of goals,” according to an internal report published in 2013.

While DHSTogether “initially focused on suicide prevention,” the report continues, the agency “quickly recognized” that suicidal behavior is the “end result” of a “complex trajectory of events and circumstances.” The authors of the report determined that there was a need to “intervene” long before employees reach the point that they are considering suicide.

In 2012, the agency hired the government-run Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences to create a peer support program for DHSTogether, and train leaders on the relationship between stress and work performance. The 2013 internal report noted, however, that a year after the contract had been signed, “little has been accomplished.”

DHS earmarked about $1.5 million for DHSTogether, before reducing that funding to about $1 million for the 2014 fiscal year. “Because of the modest funding, few or no resources are tied to the policies that are promulgated by the program,” the internal report said.

The most recent mention of DHSTogether on the DHS website is a list of agency-specific resources, last updated in 2015. The CBP resource list links to a website that does not load, and lists a phone number for a peer support program that is no longer in operation, and an email Quartz sent to the email address listed for the program was never returned.

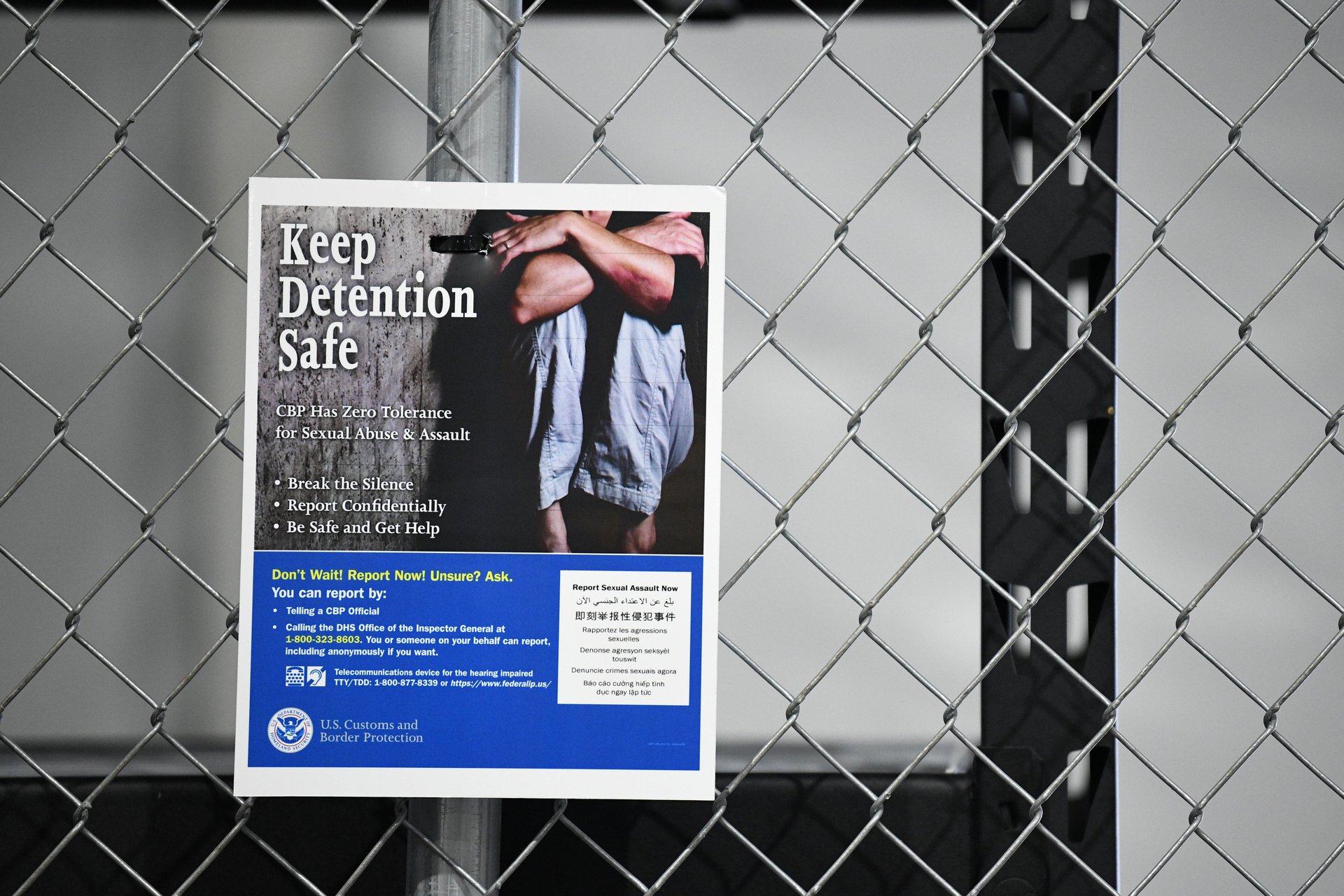

In response to Quartz’s inquires, a CBP spokesperson wrote in an email that the agency had “expanded” its resources to prevent suicide, and has held events both during Suicide Awareness Month and at other times that can be live streamed and viewed throughout the year. The spokesperson also said the agency has a peer support program, a “robust” Employee Assistance Program, and “an agency-wide” internal website dedicated to suicide prevention, which includes suicide prevention videos.

The first stop for a distressed CBP officer might be to log into the EAP website. But given the high rate of suicide and mental health problems at the agency, and its apparent years-long effort to address those problems, the website’s options for help are surprisingly thin.

On the login page, the portal first directs employees to call a 24-hour hotline, which is industry standard. Using the login password on the Department of Homeland Security’s own website, Quartz logged into the portal in June, and found a website administered by Espry, a private contractor.

The portal homepage includes several links to issue-specific pages. The “suicide prevention” page link features a stock image of several people in silhouette helping a person up from a cliff. The “videos” tab on the suicide prevention page links to a single video. It is titled, “Teen suicide: Too young to die.” The video is under copyright from NBC Universal and features a psychologist discussing suicide among teenagers. The psychologist in the video, Dr. Peter Jensen, told Quartz it was taped in early 2001.

Other features of the suicide prevention portal include a link to a questionnaire to screen for depression, and various links to articles about suicide prevention from other groups, including the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline website.

In another failed effort, last fiscal year CBP hired Federal Occupational Health (FOH), a private company that operates Employee Assistance Programs. As part of a pilot program, the company worked with a special CBP task force, which decided to try staffing ports of entry with liaisons who could point employees to the various mental health benefits available.

The pilot was intended to take place in San Diego, home to one of the busiest ports of entry along the southern border, according to an FOH employee who hung up the phone before giving their name. But the one-year pilot ended before the company managed to recruit someone to fill that position, and funding for it wasn’t renewed.

James Phelps, a professor of criminal justice who studies border enforcement and is in regular contact with CBP officers, told Quartz that officers have confided in him that they’ve been victims of outright intimidation—used to prevent employees from seeking help.

On June 13, CBP announced it had hired a certified trauma specialist to work with air and marine officers following several upsetting incidents. However, Phelps said the vast majority of them won’t ask for help.

“And the reason is because they’ve been directed by their bosses not to,” Phelps said. “The human resources guy or gal will walk in and say, ‘We want to remind you, we’ve expanded this, we’ve expanded that. These things are available to you.’ And then after they leave, the supervisor of the shift walks in and says, ‘Anybody who takes advantage of that is a wimp, a pussy, and I don’t want you working in my station.’ It’s not a joke, they really are doing that.”