Does the North Pole belong to Canada?

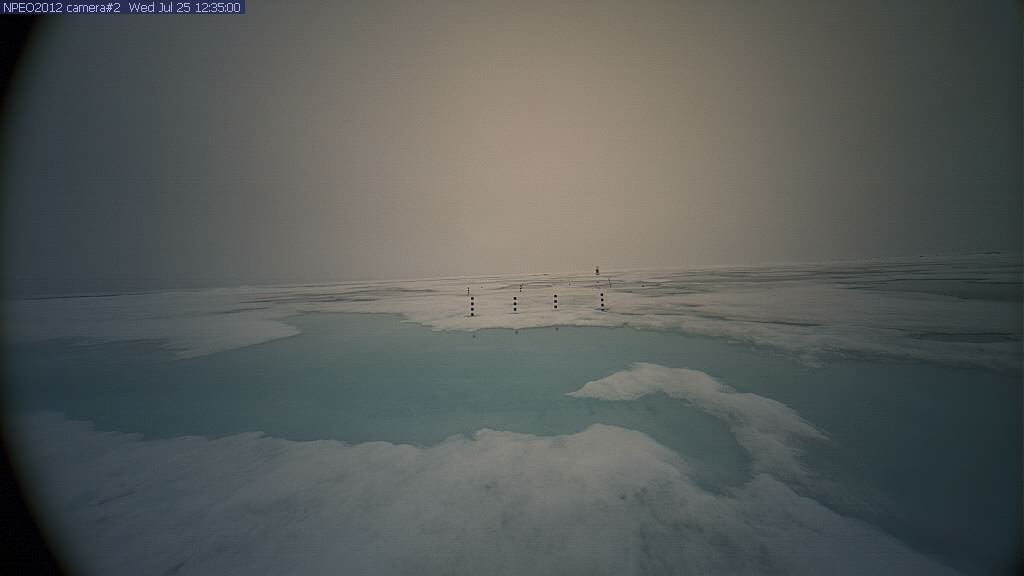

In 2007, up at the top of the world, Russia dropped a titanium Russian flag two and a half miles underwater, at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean. There was nothing much around. Just vast floes of sea ice and the two Russian submarines that had made the arduous trek to stake a claim to the North Pole.

In 2007, up at the top of the world, Russia dropped a titanium Russian flag two and a half miles underwater, at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean. There was nothing much around. Just vast floes of sea ice and the two Russian submarines that had made the arduous trek to stake a claim to the North Pole.

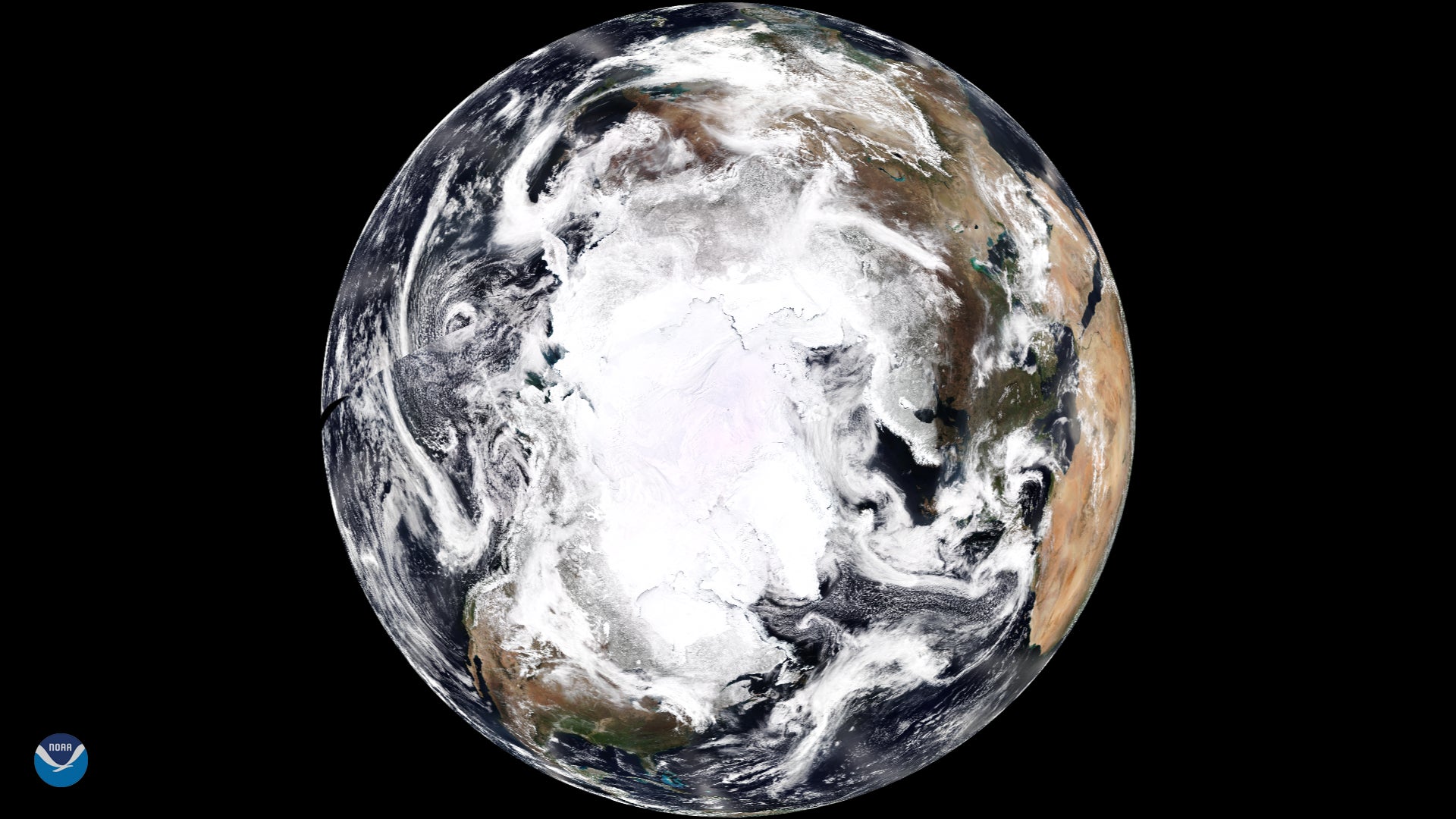

The northernmost place on Earth is hardly a place at all: It is a featureless spot in the middle of the Arctic Ocean, covered by shifting masses of ice. And yet everyone seems to want it.

This May, after a decade of preparation, Canada threw its bid in the ring, submitting a report to the United Nations Oceans and Law of the Sea Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, claiming that the North Pole should be its territory. Denmark did the same thing back in 2014, claiming the North Pole was really an underwater part of Greenland. And in 2015, years after the flag stunt, Russia submitted a formal claim that the North Pole should be theirs.

But why the North Pole? One hypothetical reason would be for future oil and gas drilling: The Arctic as a whole could contain as much as 22 percent of the world’s untapped oil and natural gas reserves. But the payoff is likely dismal, because most untapped reserves fall within countries’ established territories. In the part of the Arctic Ocean still up for grabs—including the North Pole—the probability of discovering a major source of oil is less than 10 percent, according to a US Geological Survey report from 2008.

“There’s nothing that’s of commercial value out there. It would be decades before there would be any exploitation of resources,” says Betsy Baker, the executive director of the North Pacific Research Board and an expert in Arctic Ocean governance.

Everyone, it seems, simply wants to stake their flag on the top of the world. And they’re willing to pour enormous scientific resources into the claim.

So you want to claim the North Pole

Arctic nations do have a procedure for divvying up the region. In 2008, Denmark, Norway, Canada, Russia and the United States—the countries with land bordering the Arctic Ocean—signed a declaration in Ilulissat, Greenland to divide Arctic ocean territory according to the United Nations’ Law of the Sea. Each nation gets exclusive economic rights to the area where its continental shelf extends into the ocean, up to 200 nautical miles beyond its coast.

But the North Pole is well beyond 200 nautical miles from any country’s coast. That’s where things get scientifically interesting—and excruciatingly slow.

If a country wants to claim a piece of far-off seabed, it has to make a compelling case that the area is actually a continuation of its continental shelf. To do that, they need rigorous scientific data—data that takes years to collect, because research ships can only sail for a few ice-free weeks a year.

Canada goes all in

In 2013, after years of data collection that cost more than $100 million, Canada was about to submit its Arctic claim to the UN Law of the Sea Commission. But Stephen Harper, Canada’s prime minister at the time, yanked it at the last minute, according to Ron Macnab, a retired marine geophysicist with Geological Survey of Canada, and a past chairman of an advisory board for the Law of the Sea.

Why? Because Canada’s scientists hadn’t included the North Pole in the claim, and Harper wanted it in there. Canada’s scientists were told by the administration to keep researching, to ensure that their submission “includes Canada’s claim to the North Pole,” the country’s then-foreign affairs minister announced.

“Arctic sovereignty is a hot button issue in Canadian politics,” says Michael Byers, a research chair at the University of British Columbia and an expert on Arctic politics. “As a result, no Canadian politician wants to admit that the seabed at the North Pole might fall under Danish or Russian jurisdiction. So they just keep punting the ball, even though, at some point, they know that they’ll have to negotiate boundaries.”

Now, finally, Canada has submitted their claim. The Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada put out a statement saying that they support claims beyond Canada’s land territory. “Inuit use the sea ice beyond the boundaries drawn on maps as our highways and sources of food security,” ICC Canada President Monica Ell-Kanayuk said in the statement.

But it will be years before the country hears whether its supporting data is sound enough for the UN. The commission is so backlogged (it handles oceanic territorial disputes from all over) that a decision can take a decade or more.

The UN commission recently told Russia its data looked sound—but they could just as easily say the same of Canada and Denmark’s claims. As a scientific body, it can’t settle diplomatic disputes, but whatever it decides is sure to loom large in future negotiations. A country trying to claim Arctic territory without endorsement from the commission wouldn’t have much of a leg to stand on.

“There’s a very real chance that all three countries will have put forth claims based on good scientific evidence,” Adam Lajeunesse, a research fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, told the Barents Observer. “Ultimately this will be a political resolution, not something resolved by the United Nations.”

But this will be neither a “race” nor a “fight” for the Arctic. It’s more of a slow, meticulous science-driven volley. “They’re not going to fight a war over the North Pole. It’s a featureless region of the ocean,” says Baker. Competing claims are part of the game. “That’s not a problem. That’s how this whole system is set up.”

For now, at least, no one owns the top of the world.