Here are 3.82 trillion reasons China has a big problem on its hands

China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, has the largest stash of foreign reserves of any in the world. But it’s tired of being so loaded.

China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, has the largest stash of foreign reserves of any in the world. But it’s tired of being so loaded.

In November, Yi Gang, the PBOC’s deputy governor said, “It’s no longer in China’s favor to accumulate foreign-exchange reserves.”

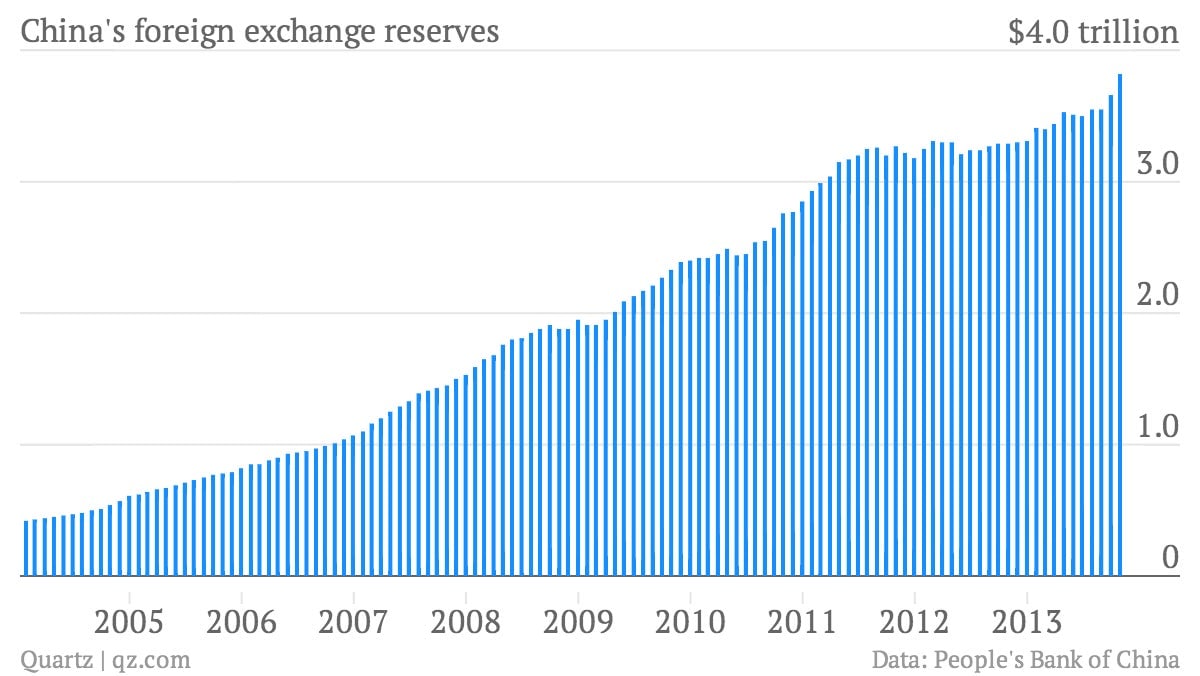

And yet, the huge wad of US dollars (which make up the bulk of its foreign currency) just keeps getting bigger. In 2013, China amassed $508 billion in foreign reserves, a big jump from the previous year’s $130 billion. It now has $3.82 trillion (link in Chinese).

This is a problem for several reasons. There’s the simple fact that it’s really hard to preserve the value of such a colossal sum of money, which is one reason behind its stated dollar fatigue.

And if the PBOC doesn’t maintain the cash pile, the value of the yuan will rise, causing Chinese exports to be much less competitive.

Here’s why: The central bank loosely pegs the value of the yuan to the dollar. That means that any time demand for yuan surges—when there are more exports than imports, or more foreign investment coming into China than flowing out—it has to buy dollars in order to maintain its desired value.

This puts the PBOC in a tricky spot. The more investors expect the yuan to strengthen, the more they demand it. That puts pressure on the PBOC to let the yuan strengthen against the dollar a little bit more—whipping up expectations that it will appreciate even more.

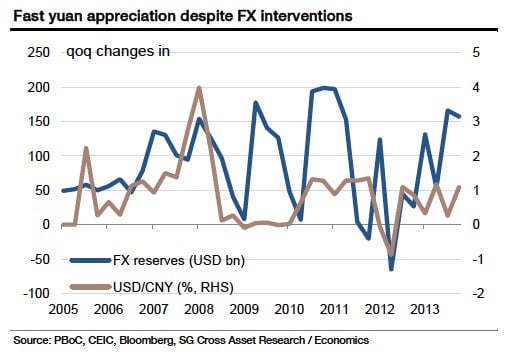

That self-perpetuating cycle is exactly what happened last year:

Société Générale’s Wei Yao said in a note today that the PBOC has given investors the wrong impression. By buying so many dollars, the PBOC is signaling to investors that yuan appreciation is a policy choice, even though it’s not, she says. If it stops intervening, the trade gap and other factors might make the yuan strengthen a bit in 2014, but speculators would exit the market.

That would be a good thing not just for Chinese exporters. Capital inflows through faked trade invoicing often flow into shadow banking, as off-balance-sheet lending is known, in order to profit on high rates. Those inflows of money seemingly keep the interbank market from going haywire; that’s likely why a government crackdown on export invoicing in May led to June’s liquidity squeeze.

The government backed off of faked invoicing after that episode. But a new policy announced in December suggests it might be gearing up for another battle royale with the trade-fakers. That will ease pressure on the PBOC to keep buying dollars. Unfortunately, a stronger yuan isn’t the worst of the central bank’s problems. It’s also contending with the competing objectives of keeping the lid on its foreign currency reserves, deterring yuan speculators and preventing a banking crisis.