The centrists went after the progressives in night one of the second primary debate

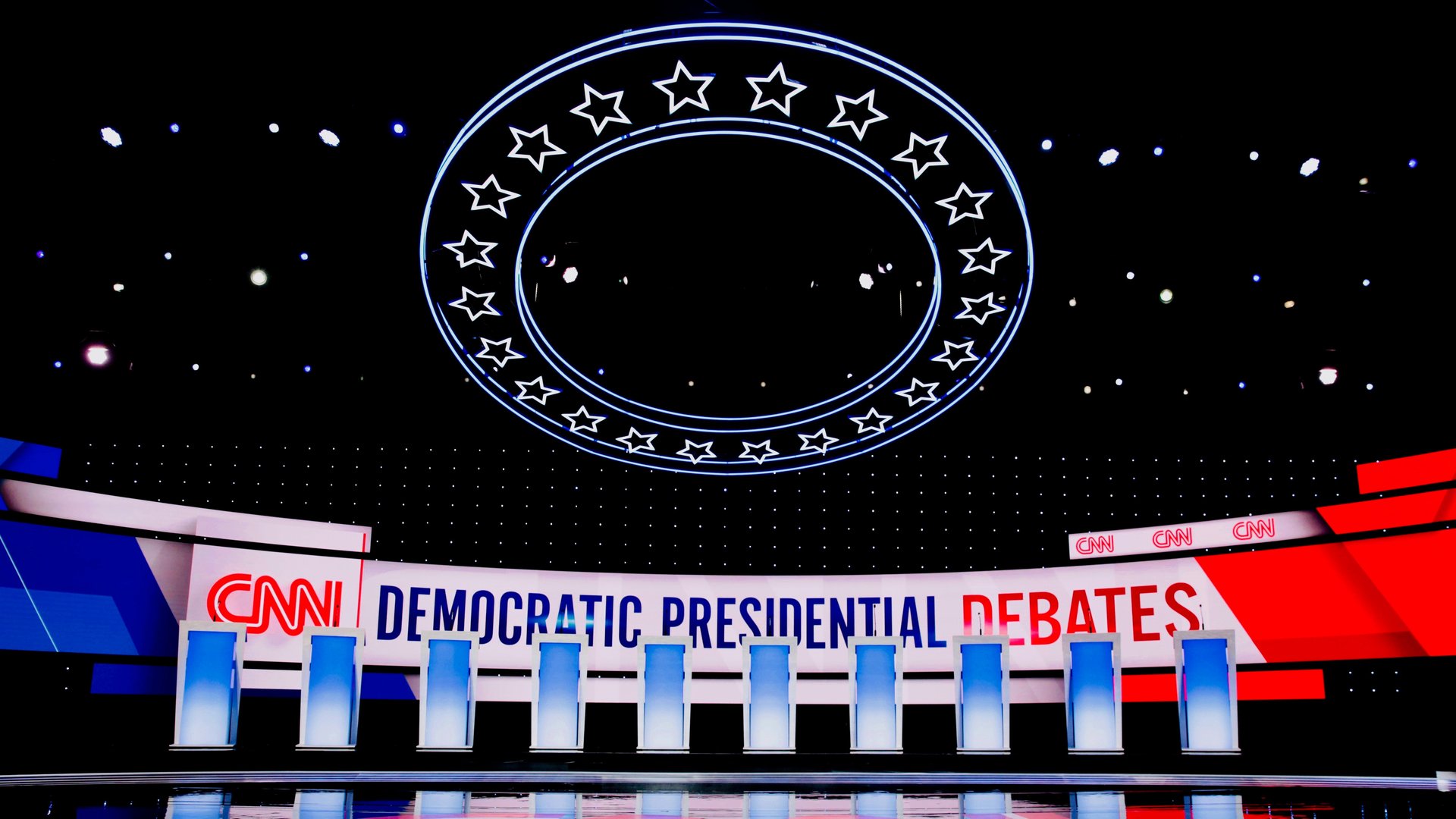

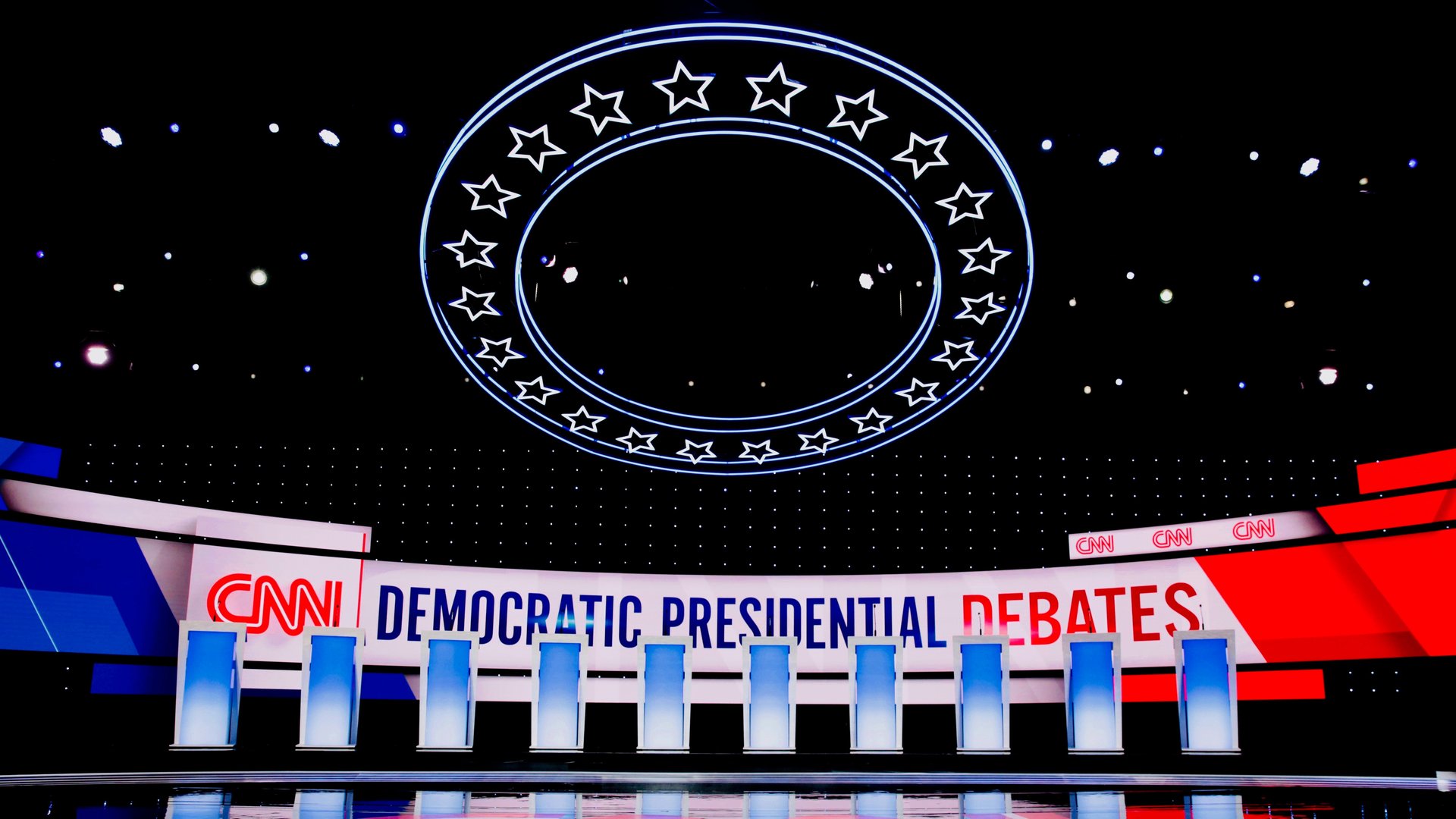

“Live from Detroit, it’s the Democratic presidential debate!” So began CNN’s coverage of the first night of the second debate ahead of the 2020 election. There were 10 candidates, three moderators, and lots of declarations.

“Live from Detroit, it’s the Democratic presidential debate!” So began CNN’s coverage of the first night of the second debate ahead of the 2020 election. There were 10 candidates, three moderators, and lots of declarations.

It was, to some degree, an argument between people who mostly more or less agree—at least on the need to unseat president Donald Trump.

But some candidates—like former Maryland representative John Delaney, Ohio representative Tim Ryan, former Colorado governor John Hickenlooper, Minnesota senator Amy Klobuchar, and debate newcomer Montana governor Steven Bullock—angled for the position of electable centrist. They spent most of the debate trying to set themselves apart from the progressive stalwarts, Vermont senator Bernie Sanders and Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren, who shared center stage as the candidates now polling the best.

South Bend, Indiana mayor Pete Buttigieg and former Texas state representative Beto O’Rourke were a bit left of center but fell short of supporting Medicare for All.

Self-help guru Marianne Williamson was in her own independent category, the anti-politics politician. Williamson wore black instead of the mint-colored suit she donned in June and, along with a more somber costume, appeared more intent on being taken seriously by sounding angry instead of talking calmly about love. She was critical of wonkiness and intellectuals and political insiders, saying she wants a “politics that speaks to the heart,” while sounding unusually outraged herself. At one point she referred to the “dark, psychic force and collectivized hatred” that Trump “is bringing up in this country.”

Candidates seemed to take notes from the last debates in June. Klobuchar toned down the mid-Western folksiness she emphasized last time with down-home aphorisms. O’Rourke, who began his performance on the stage in June in Spanish, stuck to English. Ryan seemed a bit livelier than he did before—his pallor last time was alarming—but continued to mostly bore except when he referred to “people who shower after work.”

Warren appeared confident and calm, calling out moderates who criticized her big ideas and reiterating the theme that she’s a fighter. “I don’t know why anyone goes to the trouble of running for president just to talk about what we can’t do,” Warren told Delaney, who wanted to talk about “kitchen table and pocketbook” economics and criticized her grand economic plans. “I’m ready to get in this fight.”

Sanders got a few laughs. Responding to Delaney’s claim that Sanders was unfamiliar with the Medicare for All bill, Sanders muttered, “I wrote the damn bill.” But he was mostly angry—about health care, homelessness, greedy corporations, tax rates, Trump, immigration—so much so that at one point Ryan told Sanders, “You don’t have to yell, Bernie.”

Bullock had a favorite phrase. He expressed disdain for “wish list economics” repeatedly, referring to policies proposed by Warren and Sanders. And he seemed to take a shine to Ryan’s people—you know, the ones who shower after work—quoting his colleague’s formulation appreciatively.

Delaney, for his part, seemed intent on being the least likable person on the stage. He attacked his colleagues throughout the debate, and claimed to have superior professional experience. He noted, for instance, that he worked in the healthcare industry and didn’t think his colleagues understood the business. Riffing off Bullock, Delaney spoke of “fairy tale economics” and “impossible promises.” As he did in June, he told his origin story, saying he’s a product of the American dream and reminding voters that he is the son of a union electrician who liked his employer-supplied insurance. Delaney says he wants to cure divisiveness and solve problems but he was pretty divisive on the debate stage.

Buttigieg mostly made it a point to emphasize his youth, turning a possible disadvantage into his strength. At 37, he is the youngest candidate, as is especially evident when he says things like, “High school is hard enough without having to worry about getting shot,” and looks as if he graduated not so long ago himself.

Hickenlooper emphasized that it was a time for evolution rather than revolution. He seemed relaxed but perhaps not totally prepared, despite claiming to be pragmatic. And he was gracious. Hickenlooper agreed with Warren that the wealthy should pay more in taxes, including him. He began his closing statement with an enthusiastic assessment of the event that sums it up best, “And what a night! I loved it.”