Climate change is luring cruise ships to sail risky Arctic passages

On August 27, 2010, in Canadian waters above the Arctic Circle, a cruise ship called the Clipper Adventurer ran aground on a rock no one knew was there. Two hundred passengers and crew had set out on an adventure few tourists have experienced: a journey through the Northwest Passage.

On August 27, 2010, in Canadian waters above the Arctic Circle, a cruise ship called the Clipper Adventurer ran aground on a rock no one knew was there. Two hundred passengers and crew had set out on an adventure few tourists have experienced: a journey through the Northwest Passage.

The ship, a 295-foot (90-meter) vessel operated by the travel company Adventure Canada, struck the rock early on a Friday evening. The closest humans were in coastal Kugluktuk, 55 miles away, a mostly Inuit community of about 1,400 people in the Canadian Arctic region of Nunavut. A Canadian icebreaker, surveying waters 500 miles away, changed course to conduct a rescue operation. It arrived on Sunday.

The weather was calm and sunny, which meant the two-day wait wasn’t dangerous; everyone was fine. But that’s hardly a given that far north, where storms and extreme conditions can roll in quickly. And in the vast Canadian Arctic, fewer than 10% of the waters are charted. As more ships brave the territory—encouraged by passageways thawed by temperatures rising faster than anywhere else on Earth—the likelihood of a dangerous grounding increases.

“The uncharted rock on which our ship ran aground is just one fragment of an entire world we have yet to perceive,” Kathleen Winter, a passenger on the cruise, wrote later.

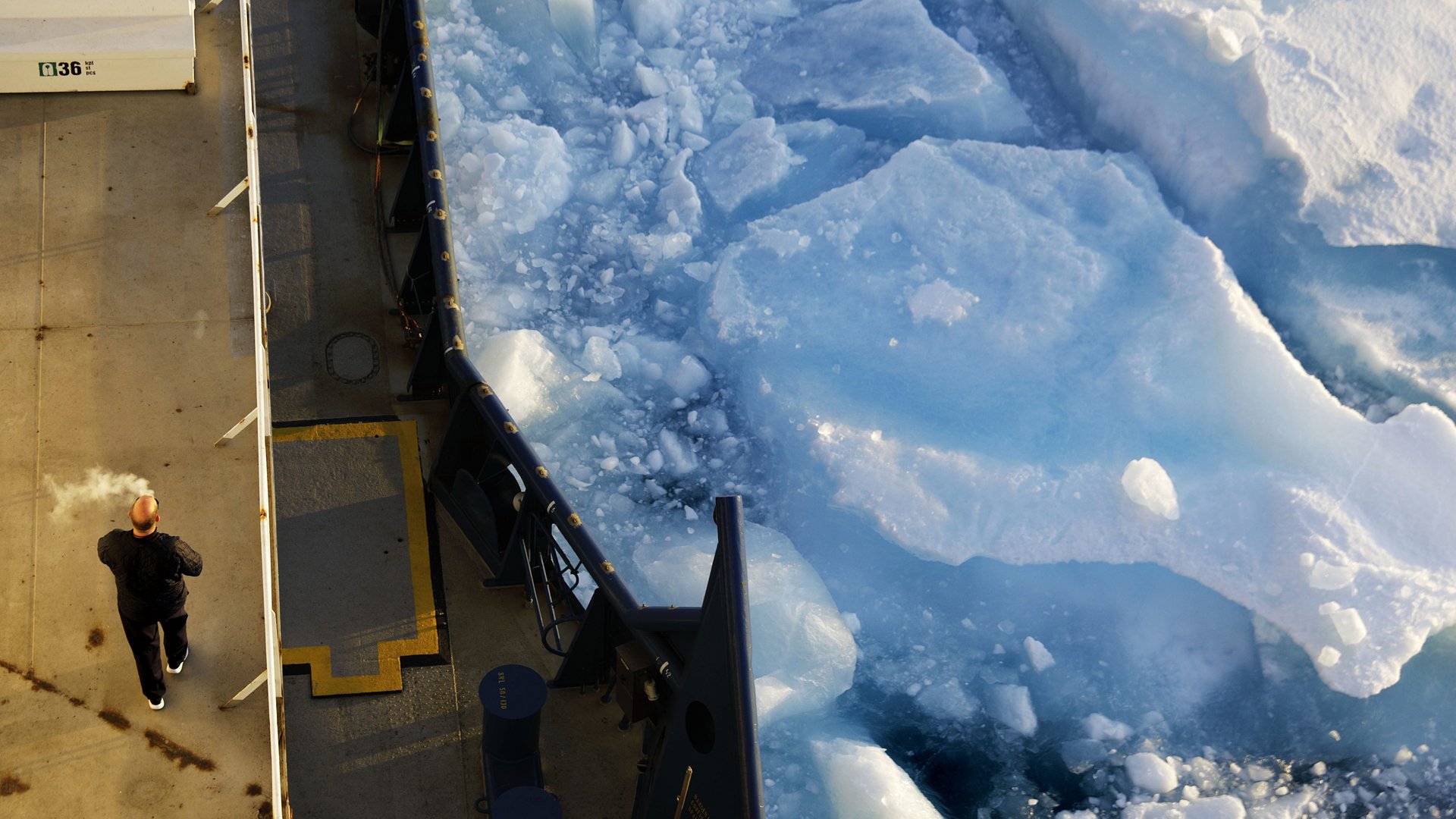

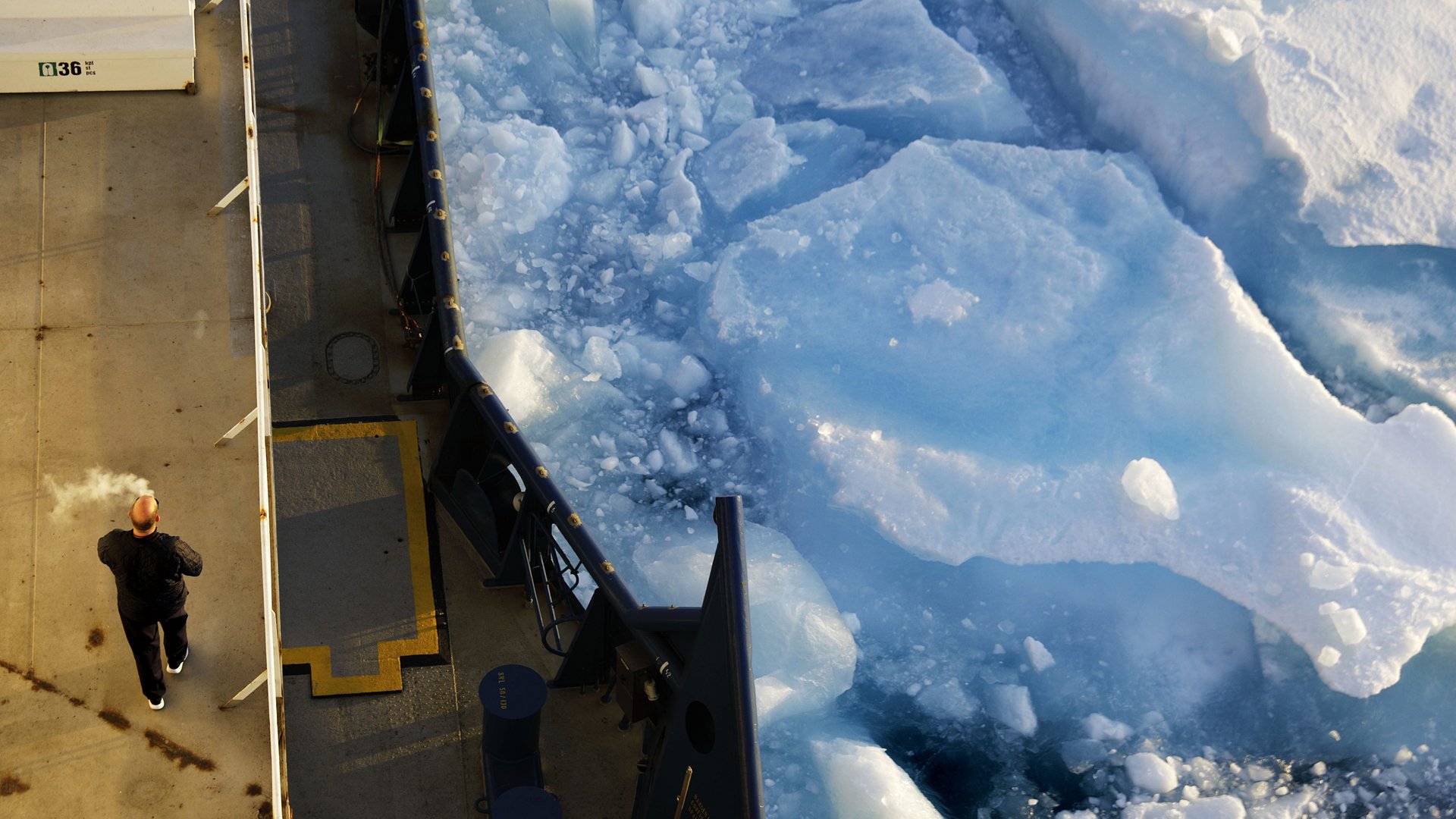

The rise in Arctic passages is slow but steady. Canada, which used to expect just a few yacht voyages a year, is now dealing with almost two dozen. Vessels of all kinds—including cargo ships—are on the rise too, and the number of trips taken in Canadian Arctic waters nearly doubled in the last decade. That’s thanks to hotter summers that now melt even so-called “multi-year” ice, which used to stay frozen year-round. Places where sea ice thawed for a few days or weeks in summer are now ice-free for longer.

But ice-free doesn’t mean danger-free.

“Most people don’t realize this, just how dangerous it is,” says Michael Byers, a research chair at the University of British Columbia and an expert on Arctic politics. “It’s very remote. There’s no coastal infrastructure, so no ports of refuge. There’s extreme weather. The maritime maps are quite poor.” Even the fact that there’s less sea ice poses a threat: It means there’s more sections of broken-off ice in the ocean, which is always on the move. Small pieces of glacier called “growlers” pose a particular threat. “They’re the same density as concrete. They can punch a hole in a ship if they’re struck,” says Byers.

And then there’s the freezing sea spray. “If you’re sailing on an ice-free ocean in a storm and the air temperature is below freezing, the spray from the waves can freeze and cause a ship to overturn. It’s destabilizing,” Byers says. “I’ve been in the Northwest Passage in those sorts of conditions, on ice breakers. They have axes for chopping ice off of the superstructure.”

Underwater rocks, like the one that stranded the Clipper Adventurer, are an ever-present danger. In August 2018, another cruise ship struck a rock, also off the coast of Nunavut. The ship, operated by Canadian cruise company One Ocean Expeditions, was carrying 162 passengers and crew. The rescue operation cost the Canadian armed forces half a million dollars. The cost to the Canadian Coast Guard, the primary branch involved in the rescue, was not disclosed.

Russia later canceled the leases of two of One Ocean’s cruise ships.

Just this March, a cruise ship’s engines broke down off the coast of Norway with more than 1,300 passengers on board. Helicopter rescue teams managed to airlift 500 people off the ship, and it was headed for a collision with rocks while 800 people were still on board, Byers says. By a stroke of luck, the ship’s crew managed to restart the engine before that could happen. But the near-miss signals another problem: “When you talk about large ships, you just can’t get people off in time,” he says.

“Any kind of activity is dangerous,” says Byers.”“It’s never going to be a place where ships can just sail through willy-nilly.”

The Canadian Coast Guard knows it has a growing challenge on its hands. “We are seeing an increase. That being said, we’re still dealing with very small numbers here,” says Neil O’Rourke, a senior official in the Canadian Coast Guard. But they expect passages to rise more, which means they have to beef up their search and rescue capacity. “We don’t want the increase in traffic to come without the resources in place,” he says.

The Coast Guard recently reorganized to create a special Arctic region, appointing O’Rourke as its assistant commissioner.

In particular, the rise in the number of relatively small “pleasure craft” is posing unique problems to search and rescue. Yachts trying to take on the Northwest Passage increasingly meet unforeseen obstacles. “We have noticed in the last few years that climate change for us is resulting in unpredictable conditions. In the past, it was pretty certain if you were in a certain part of the Arctic at a certain week of the year, the ice would be a specific way,” O’Rourke says. Now it’s often a wild card.

“Sometimes it can take us a couple of days to find the people,” O’Rourke says. “Even with air craft, good weather conditions, and ships, it can take a few days. You’re in such a huge area.”

Canada recently changed its maritime laws to stipulate that vessels carrying 12 people or more must have automatic identification systems on board, which use transponders to alert the coast guard to their location. The old rule only required them on fairly large vessels of 300 gross tons or more (or 100 gross tons if it was carrying fuel oil) which meant the rule missed most private yachts.

Last year, the Canadian Coast Guard opened a rescue boat station in Rankin Inlet, off Canada’s Hudson Bay. It’s the first permanent Coast Guard station for search and rescue in the Arctic, O’Rourke says, and it is staffed entirely by Inuit people hired from the local community.

They’re also setting up what O’Rourke calls “Coast Guard auxiliary units” in remote Arctic coastal communities. There, the Coast Guard trains local volunteers and helps them procure a boat they could use to rescue people if necessary. They plant to bring four more auxiliary units on line this year.

And then there’s the uncharted rocks. “They know more about the surface of Mars than this area,” Ryan Harris, a member of the 2010 Arctic Survey team reportedly said the year the Clipper Adventurer ran aground. The rock it collided with hadn’t made it onto a single map in the 113 years since the first Northwest Passage expedition.

But Canada is slowly filling in the gaps. Now, each time one of its fleet of 15 icebreakers comes in for major repairs, engineers install multibeam sonar technology onboard—a process that involves drilling a hole in the side of a ship the size of a car, according to O’Rourke. The technology, which is installed on four icebreakers so far, sweeps the sea floor, updating charts as the ships go about their business.

Sailing in the Arctic will never be simple. It will probably never even be particularly safe. But as climate change tempts more adventurers, the potential for tragedy increases too. Canada is doing its best to keep up. But, O’Rourke says, common sense is key. “People should be well prepared, like any time you go out into nature and away from civilization.”