Europe’s battery leadership can help clean up the global metals supply chain

Lithium-ion batteries hold the key to a future powered by clean energy. By enabling electric cars, ships, and planes, this versatile energy-storage medium is bound to help cut pollutants and greenhouse gases.

Lithium-ion batteries hold the key to a future powered by clean energy. By enabling electric cars, ships, and planes, this versatile energy-storage medium is bound to help cut pollutants and greenhouse gases.

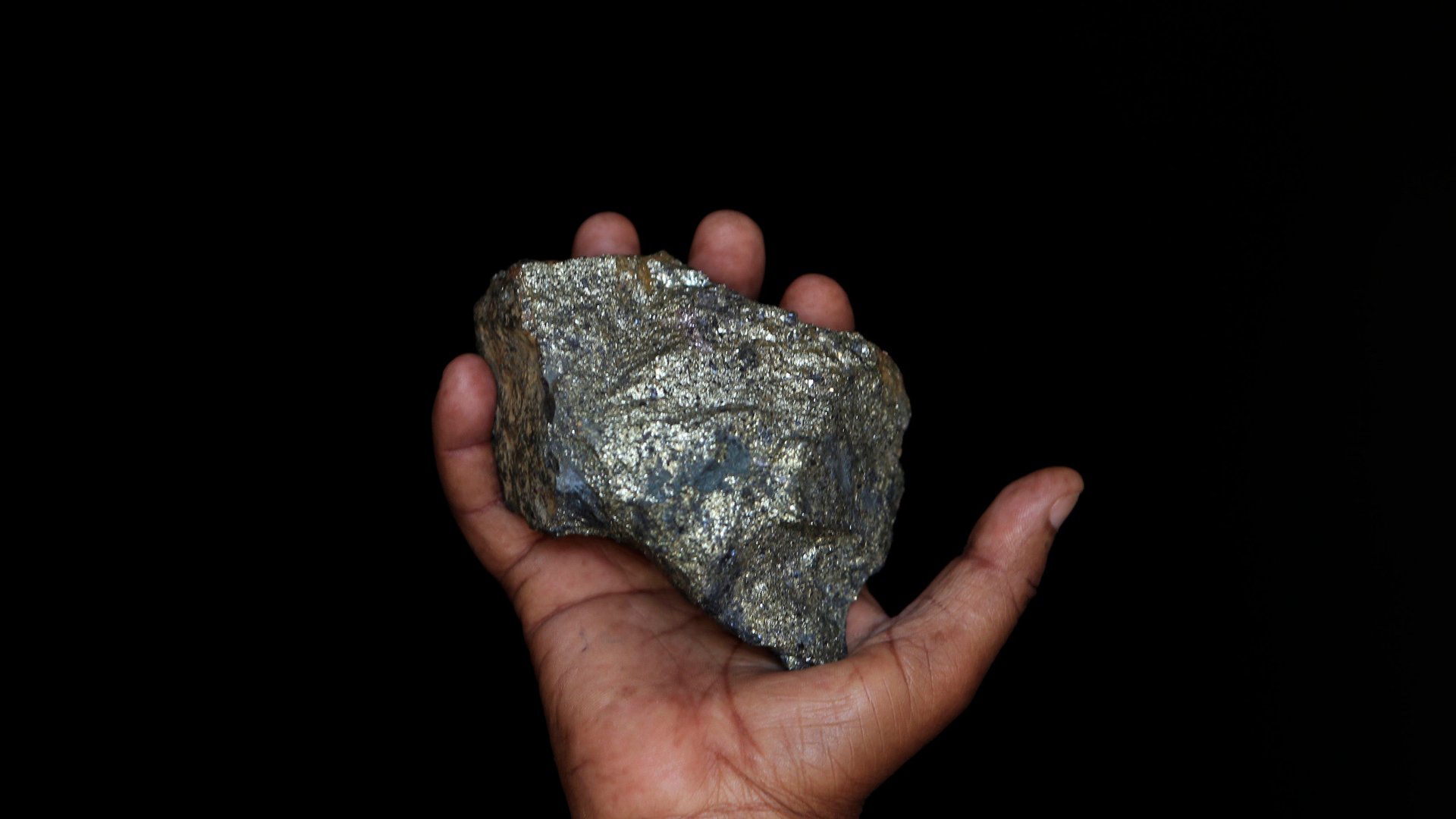

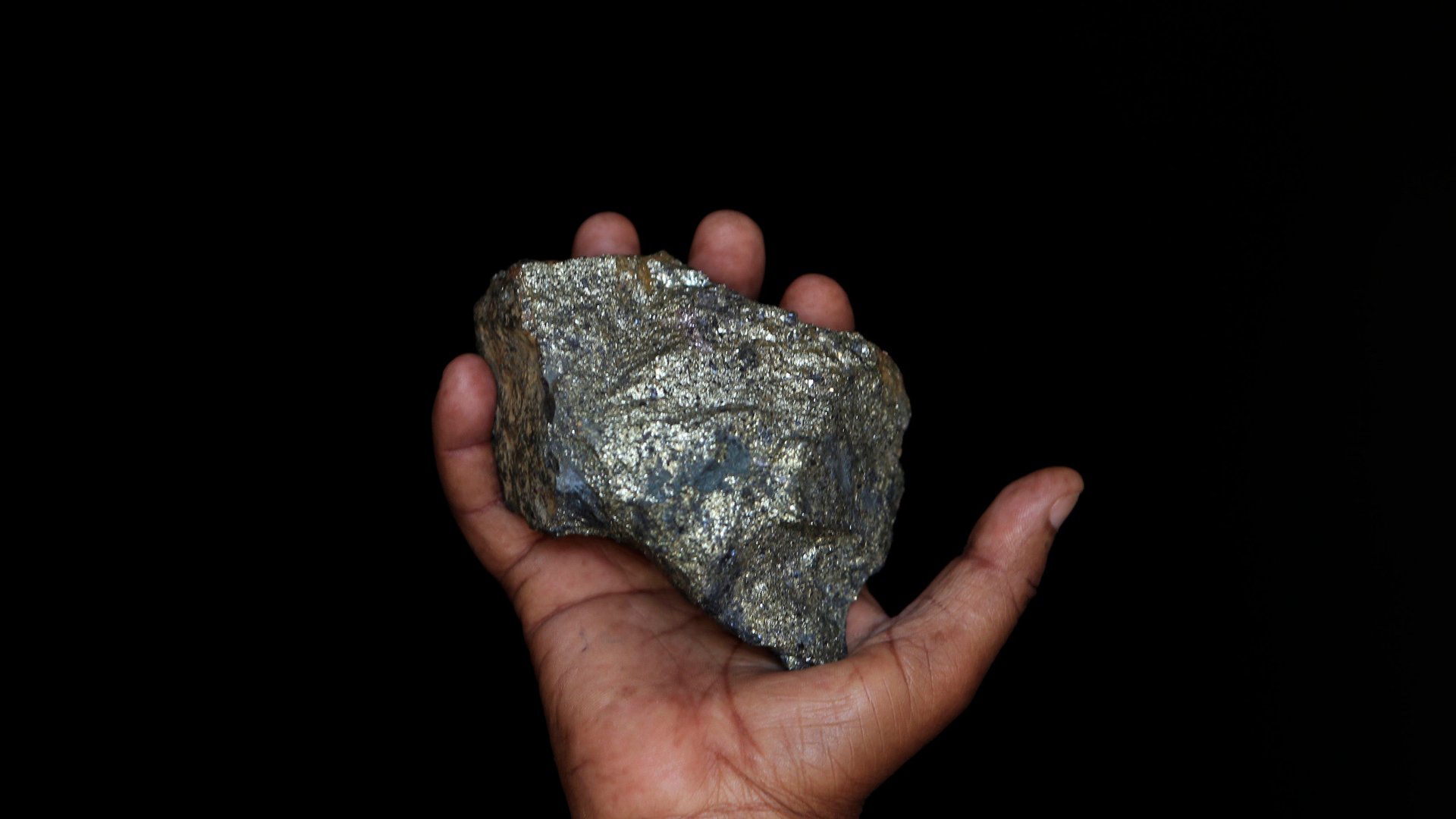

But all that progress will come at a cost. Battery manufacturing requires large amounts of metals, some of which, like copper and aluminum, are plentiful and easy to mine. The rarer materials like cobalt and lithium, though, often come from places rife with war and child labor.

About 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and a 2016 Amnesty report found there is little doubt that at least 20% of the country’s cobalt supply involves the exploitation of children. Much of it ends up in China, where it’s packaged into batteries for smartphones, drones, and increasingly electric vehicles.

While China has formal guidelines to meet international standards for responsible mineral sourcing, according to Andy Leyland of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, it’s still “very difficult” to audit whether a batch of cobalt may or may not contain metals from unethical mines. But things on that front might soon change, as Europe positions itself to become a major battery manufacturing hub.

Europe’s push on electric cars is forcing carmakers to lock down a consistent, local supply of batteries. The commitments are coming in the form of billions of euros in investment. That’s attracting large battery companies to the region—all of which need to secure their own metals supply chain.

And European carmakers are committed to cleaning up that supply, says Leyland. That isn’t just because Europe has stronger regulations, but because European customers expect higher standards.

Some of these European battery manufacturing plants, including the largest one planned by CATL, are likely to be built by the same Chinese battery companies that have trouble auditing their metals in their home country. Leyland expects that, once in Europe, these companies will follow the better practices demanded on the continent.

A report on the geopolitics of electric vehicles by E3G, an environmental think tank, recommends that the EU should work with countries like the DRC to pass laws governing metals mining and start fixing the underlying poverty and corruption that lead to forced employment of children. If European carmakers only buy ethical metals, it will provide the economic incentive to push countries in the right direction.

Europe is also likely to accelerate the efforts to recycle lithium-ion batteries. The continent’s strict regulations on collection and recycling of lead-acid and nickel-cadmium batteries could serve as a blueprint, even if the technology needed to recover the materials inside lithium-ion batteries is likely to be different.

Increased recycling will mean that used batteries don’t end up polluting the environment. The bigger win will be cutting the need for the extraction of virgin metals. The demand for metals needed in batteries is expected to grow between 500% and 1000% in the next decade.