Chairman Mao is making an appearance at the Hong Kong protests

In all their creativity, the Hong Kong protests have sometimes surfaced unexpected figures.

In all their creativity, the Hong Kong protests have sometimes surfaced unexpected figures.

The ubiquity of Pepe the Frog, for example, has puzzled overseas observers who may not know that it doesn’t have right-wing connotations outside of the US. Then there is the Japanese robotic cat Doraemon, which China has accused of subverting the minds of young people, and who has been gracing Lennon Walls since the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement. Now a much less imaginary character is also surfacing: Mao Zedong, the Communist leader who established the People’s Republic of China 70 years ago.

One of the founders of the Communist Party of China, he is remembered for his “cult of personality,” for agricultural and industrial policies that led to the starvation of tens of millions of people during the Great Leap Forward, and for elevating class struggle to a devastating “all against all” form during the decade of the Cultural Revolution in an attempt to secure loyalty to himself. Many mainland Chinese escaped at that time to Hong Kong at extreme personal risk—even by swimming to the shores of what was then a British colony.

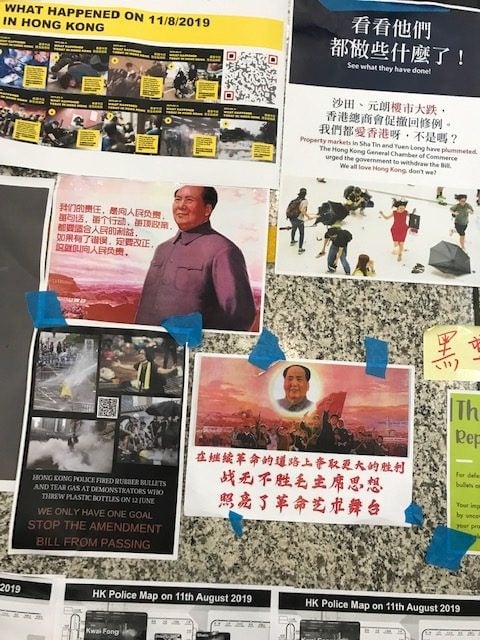

Surprisingly then, posters with Mao’s image have appeared at this summer’s protests, including at the Hong Kong International Airport when protesters occupied it for several days earlier this month.

One read: “Our responsibility is to strive to work for the people. Every sentence, every action, every policy, must all be to the people’s benefit. If there are mistakes, they shall be rectified. This is what is called to work for the people.” Next to these characters, printed in red, stands Mao himself, his hands behind his back, looking satisfied, with the Great Wall in the background.

Another airport poster had graphics reminiscent of the Socialist Realism style in vogue during the Cultural Revolution itself—with a group of people emerging from the vast Chinese lands, striking a defiant pose under a red flag. Above them, filling the roundness of the sun above, is a smiling Mao. The text, written in red brushstrokes, reads: “Let’s seize an even greater victory as we continue on the road to revolution. The invincible thought of Chairman Mao illuminates revolutionary art.”

One man who was spotted putting up these posters, in his late fifties, only gave his name as Chen and brushed away questions about Mao’s brutality, saying: “He did make a revolution. His quotes are very useful.”

The irony, of course, isn’t lost on anyone: the Chinese regime came to power through a revolution that glorified a rebellion of the people has turned into a government that bans all forms of the same.

Mao is still widely visible in China—his portrait is on every banknote, hangs at the entrance of the Forbidden City overlooking Tiananmen square, and a number of gigantic statues of hime are still scattered in cities across the country. His legacy is surprisingly positive in mainland China, something that the current Chinese leader Xi Jinping seems to be banking on as he amasses the most power any Chinese leader has had since Mao’s days.

Blame for the Cultural Revolution on his death in 1976 was deflected to four people close to him—as blaming Mao himself risked delegitimizing the Communist Party. Instead, his wife, Jiang Qing, political theorist Zhang Chunqiao, the literary critic Yao Wenyuan, and the labor activist Wang Hongwen were tried and sentenced to life imprisonment. The label “Gang of Four” still resonates deeply enough that Chinese state media still apply the label to those it doesn’t like, as it did with four prominent pro-democracy advocates in Hong Kong in recent weeks.

In Hong Kong, it’s not only protesters who are quoting Mao. In a regular opinion column (link in Chinese) for newspaper AM730, Jasper Tsang, the former president of the Hong Kong legislature and the founding member of the largest local pro-Beijing party, the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, used a Mao quote to distance himself from the Beijing line that has at various times described the Hong Kong’s protests as inspired by, financed by, or masterminded by foreign forces.

Tsang says that the discontent is real, that the trust in the central government has diminished among people, and cites a phrase in Mao’s 1937 essay “On Contradiction”—“… social development is due chiefly not to external but to internal causes…”—to encourage the leadership in Hong Kong and Beijing to look at the internal causes of the current strife, and act accordingly.

And so, unexpectedly, Mao is being seen as a potential source of wisdom even by opposing sides in Hong Kong’s ongoing unrest.