The soundtrack of this year’s Hong Kong protests marks a somber turn from the Umbrella Movement

On the first night of the Umbrella Movement on Sept. 28, 2014, I watched thousands of protesters sit on the road facing a phalanx of riot police singing the Cantopop anthem “Boundless Ocean, Vast Skies” made famous by Hong Kong band Beyond.

On the first night of the Umbrella Movement on Sept. 28, 2014, I watched thousands of protesters sit on the road facing a phalanx of riot police singing the Cantopop anthem “Boundless Ocean, Vast Skies” made famous by Hong Kong band Beyond.

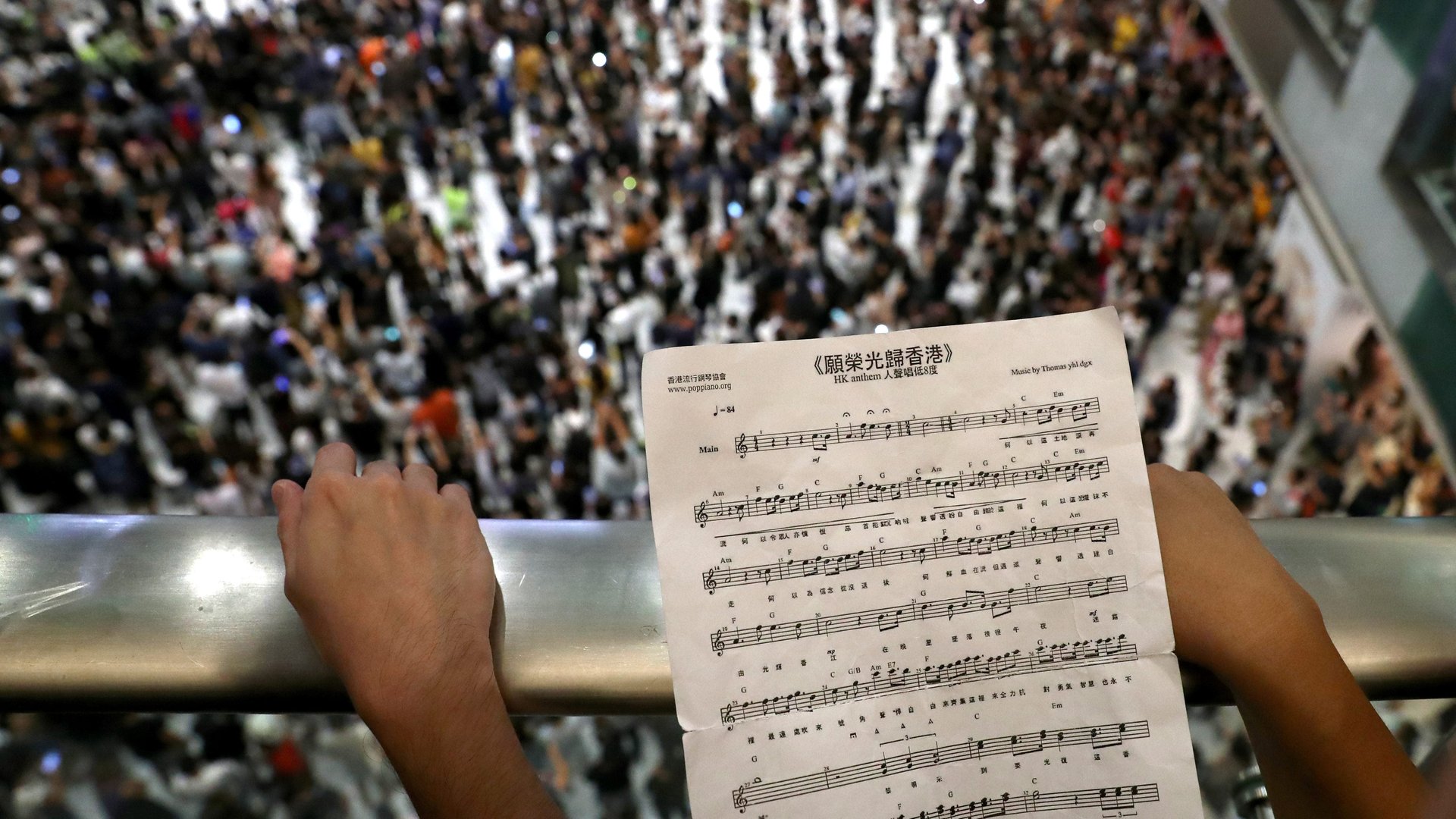

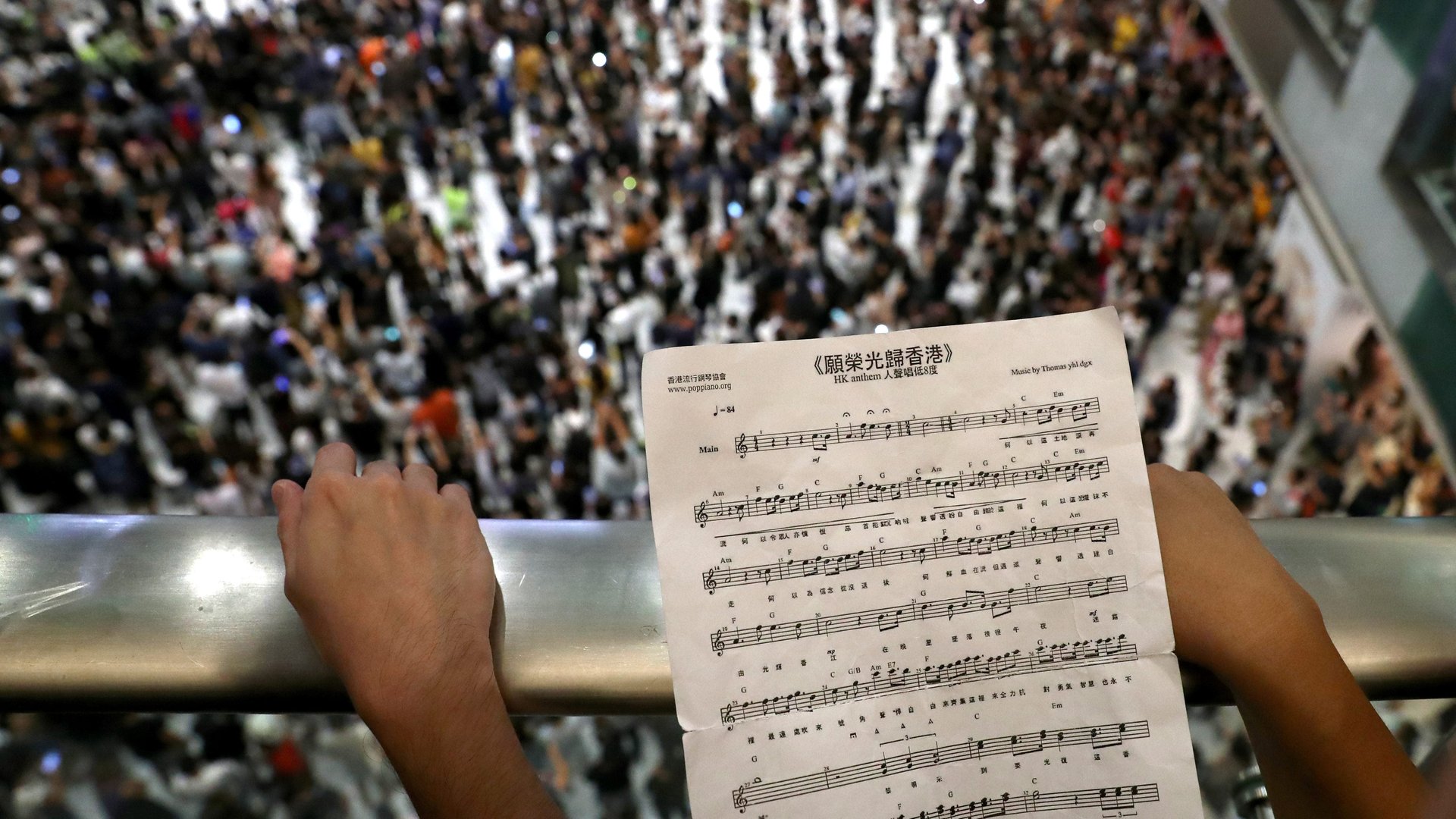

Almost exactly five years later, in the midst of ongoing protests that have rocked Hong Kong for over one hundred days, I stood in the atrium of the luxury Landmark mall as a crowd of office workers gathered to sing “Glory to Hong Kong.” The somber march, composed just a few weeks ago, is already being referred to by some protesters as Hong Kong’s “national anthem” as disillusionment grows with the idea the city’s unique character and freedoms can be preserved within China.

As Hong Kong experiences its second mass protest movement in five years, the contrast between the two movements is perhaps nowhere as striking as in their soundtracks. Music played a central role in 2014’s Umbrella Movement, which began five years ago this week in protest at Beijing’s offer of universal suffrage on the condition that candidates pass muster with a committee of 1,200 business and pro-China voters. The 79-day occupation of the city’s central business districts got its name from protesters using umbrellas to defend against pepper spray and tear gas.

As well as the Beyond anthem, another song—“Raise the Umbrellas”—was written especially for the movement by Cantopop composer Lo Hiu-pan, and recorded by a number of pop stars who supported the movement including Denise Ho, who has since become one of Hong Kong’s leading political activists. During Umbrella Movement rallies, Shiu Ka-chun, a social worker who acted as master-of-ceremonies of the Admiralty-occupied zone’s “main stage” and who was subsequently jailed for his role in the protests, would lead the crowd in singing both songs. The scene, a sea of illuminated mobile phone lights, sometimes looked more like a Cantopop concert than a political rally.

The songs were optimistic and upbeat, reflecting the utopian spirit of the movement, perhaps best summed up in a line adorning a banner at Admiralty taken from John Lennon’s “Imagine,” another song popular during the Umbrella Movement: “You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.”

Even in the rare moments of conflict, the music was playful. When pro-government antagonists entered the occupied areas and began haranguing the crowd, protesters would surround them and sing “Happy Birthday!” The collective singing of the cheerful ditty—which apparently started thanks to a well-timed accident (pdf)—would drown out the attack and defuse a potentially violent situation with humor and absurdity.

Five years later, music has also been central to 2019’s summer of discontent—what I have called the ”Hard Hat Revolution” to 2014’s “Umbrella Revolution”—but in keeping with the darker tone of this protest movement, the music has also taken a darker, at times almost funereal, turn.

This reflects the change in protest methods from the Umbrella Movement to today, according to Winnie W.C. Lai, ethnomusicologist at the University of Pennsylvania who has researched Hong Kong protest music. “Instead of peaceful occupation, protesters now ‘fight back’ whenever the police escalate their use of force. The Cantopop ballads of the Umbrella Movement do not really fit with the tense atmosphere in the protest space.”

In addition, Lai argues, music has gone from being largely expressive during the Umbrella Movement, a way for protesters to “feel good among themselves situated in their utopian community,” to being more utilitarian. This summer’s protest songs “have rather clear functions and purposes that are directly related to the people’s political will and action,” says Lai.

This was the case with “Sing Hallelujah to the Lord,” a Christian hymn composed in 1974 that became an early theme song of the current movement, which began in June in opposition to a proposed bill that would have allowed suspects to be sent to mainland China for trial. That month, protesters gathered at the protest frontlines outside government headquarters and sang the hymn in rounds, sometimes for hours at a time. Those leading the singing were initially Christian protesters, according to Dr. Ting Guo, a religious studies expert in the gender studies program at the University of Hong Kong. “Later, because of the popularity of the song, and how catchy it is, it became an anthem of the movement, so everyone would be singing along.”

Christian protesters say that they sang the song to encourage peace and non-violence. “It is a very soothing, very calming hymn. It provided a relief to the tension at the front lines of the protests,” says Guo. However as the months have worn on, the song seems to have been abandoned at the same pace as adherence to the policy of non-violence.

In recent months, as protesters have clashed violently with police, the underlying beat has been the “death rattle” of protesters beating their makeshift shields, road signs and traffic barriers. The protesters appear to have learned the tactic from police, who bang their truncheons against their riot shields as they advance to intimidate those in their path. In the hands of the protesters, the drumming serves to rally spirits as the tear gas grenades and rubber bullets pop around them.

Yet, in keeping with Hong Kong protesters’ seemingly limitless talent for satire and memes, there has also been room for some musical levity. Remixers recently deconstructed and auto-tuned a speech by entertainment figure Maria Cordero at a pro-government rally and combined it with the hit song “Chandelier” by international pop artist Sia to create an anti-police anthem, the chorus of which roughly translates as “Ah! Dirty cops!” The song quickly became an online viral sensation, and at subsequent protests the primal scream of “Ah!” is met with a crowd responding in full-throated chorus, “Dirty cops!,” providing a moment of both humor and catharsis.

Another song, “Do you hear the people sing?,” has been one of the few songs that has seemed successfully to cross over from the Umbrella Movement to today. With the massed bodies and voices defending the barricades of the occupied zones during the Umbrella Movement, the song from the hit Broadway musical Les Misérables was perhaps an obvious choice. But in the desperate atmosphere of these months, the song takes on a new significance—although it would be best not to dwell on the ultimate fate of those who defended the barricades in Paris in 1832. (Spoiler alert: the song performed in the same cafe later in the musical is called “Empty chairs at empty tables.”)

This new somber, almost martial, tone is most obvious in the latest addition to Hong Kong’s protest music repertoire, “Glory to Hong Kong.” Composed by a local Hong Kong composer who has identified himself only as “Thomas,” with the lyrics posted and workshopped in the online LIHKG forum favored by protesters, the song is reminiscent of national anthems the world over. Within a week or two of the song first making its appearance online—just a month before China celebrates its national day—it was being sung at rallies, soccer matches, and at pop-up protests in shopping malls.

Lai, the ethnomusicologist, explains, “‘Glory to Hong Kong’ is a piece of march music which fits the protesters’ methods and determination. Protesters think that the song creates a kind of solidarity and heightens their spirit.”

The sentiment was echoed by protesters I spoke to on the streets as they sang the song during a recent protest.

“This song for me is very meaningful. When I listen to this song, I think ‘This is Hong Kong,'” said Rachel, 27, a social worker who only wanted to be identified by her first name. “When the police beat our students, I feel very helpless. But when I sing this song, I feel very powerful.”

“I feel very proud of it, very emotional,” said Chong, 26, who works in sales. “It makes us feel more united. We feel the common identity of Hong Kongers.”

With lines such as, “Distant clouds will echo still our call to battle; We are fighting for Freedom,” and “Again, our blood will be shed! But ‘Forward!’ our cry rings out!” (in the English translation rendered by renowned Sinologists and translators John Minford and Geremie Barmé) the song reflects the violent struggles of recent months that have revived 2014’s calls for democracy. But the song can also be understood as containing a glimmer of brightness in the dark.

One recent Sunday night in the shopping district of Causeway Bay, at the end of a long and particularly violent day of clashes between protesters and police, a young woman stood by the roadside playing “Glory to Hong Kong” on a harmonica. When I asked what the song meant to her, she replied: “The song means hope for Hong Kong, and hope in people’s hearts.”