Are neighborhood watch apps making us safer?

These days, a smartphone of a resident of San Francisco or New York might buzz with a notification of a new Instagram post from a friend or a news update about a jump in the stock market. But in between those, a more ominous alert can catch their attention: “1.5 miles away, a woman was shot in her face,” or “0.5 miles away, fire reported on rooftop.”

These days, a smartphone of a resident of San Francisco or New York might buzz with a notification of a new Instagram post from a friend or a news update about a jump in the stock market. But in between those, a more ominous alert can catch their attention: “1.5 miles away, a woman was shot in her face,” or “0.5 miles away, fire reported on rooftop.”

This type of alert could come from one of three apps—Citizen, Neighbors, and Nextdoor—which are part of an ecosystem of online tools that, over the past decade, have become the new neighborhood watch. From their mobile phones, users are instantaneously able to find out about their neighbors’ fears and suspicions, track police scanners to discover any reported crime or emergency, and share footage from home security cameras.

The internet has helped vigilantism and conspiracy theories thrive, with its anonymous message boards, algorithm-enabled rabbit holes, and spaces for just about anyone to share their suspicions. The mobile web has brought it all to our fingertips, accessible at any moment, relevant to our precise location.

People have always been curious about crime, fearful for their safety, and yearned for community. But today, technology can supercharge these feelings, and sometimes helps people give into their worst inclinations. Privileged (often white) users are defining safety by excluding those who are already disenfranchised (usually people of color). At the same time, the platforms and devices grant tech companies and law enforcement new ways to build their networks of surveillance.

The undying appeal of a crime watch on your phone

The Citizen app helps satisfy Alex Kehr’s curiosity. Every time the 30-year-old from Los Angeles, an avid user and CEO of his own app company, hears an emergency siren, he opens the app to see what he can learn about the incident. “It’s almost like a push notification,” he said.

Narratives of crime and those tasked with fighting it have always appealed to Americans. We know this from the popularity of long-running shows like the controversial reality program Cops, or even the ripped-from-headlines Law and Order. Citizen similarly appeals to an audience’s desire for excitement, and the feeling of being “in on the action,” Sarah Esther Lageson, sociologist and professor at Rutgers University, said in an email. But the apps provide information that is more raw, and transmitted directly into your phone. It brings the practice of eavesdropping on police scanners—a domain of reporters, lawyers, and hobbyists—into the mainstream, making it easy and digestible for everyone.

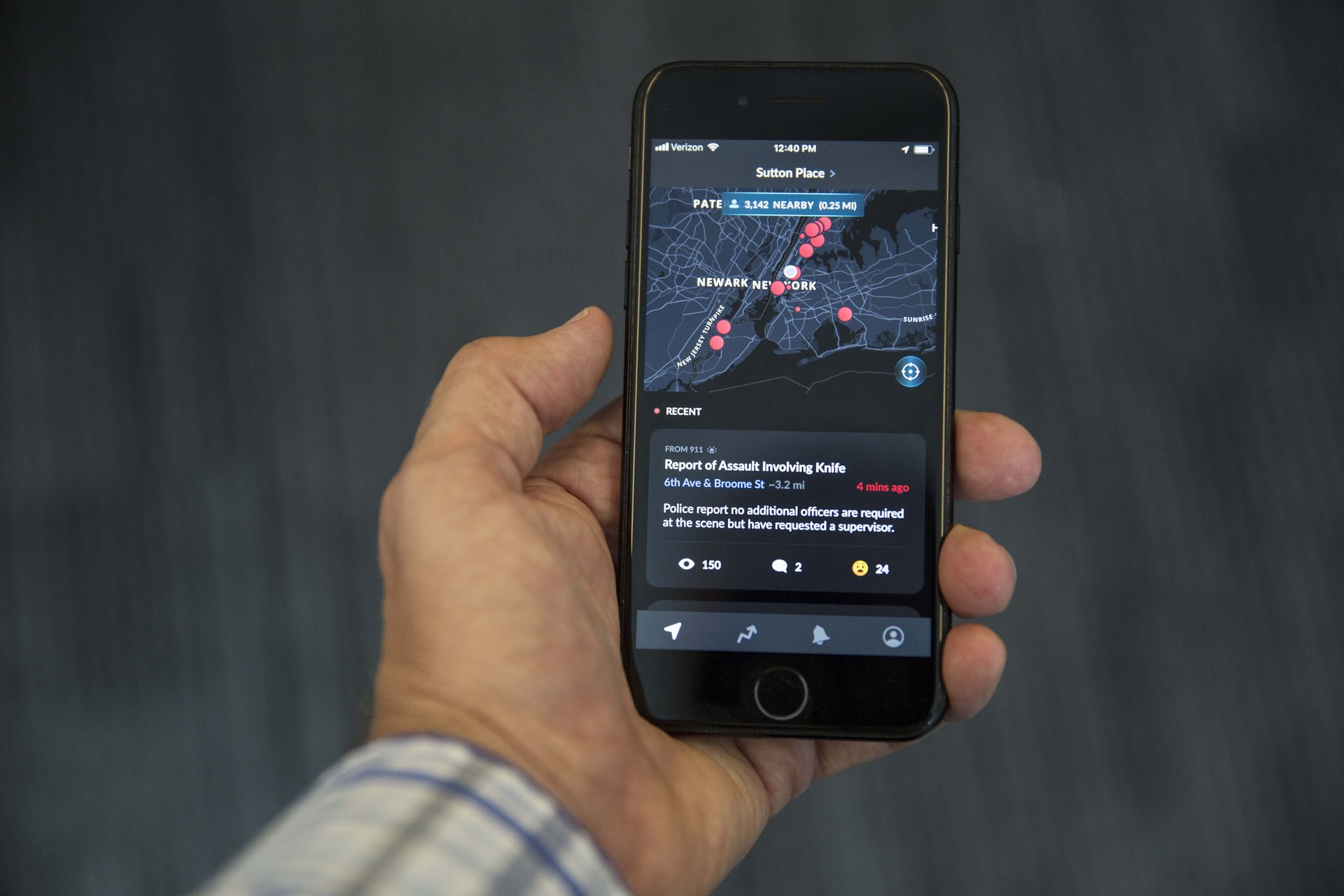

Created in 2016, Citizen, which currently has more than 1 million active users, is a police scanner on steroids. Reported crimes or incidents appear as red warning dots sprinkled around a map of a user’s location: fires, assaults, shootings, or very specific events like “irate man wielding bottle,” or “teenagers fighting.” The information is sucked up from police radio and other emergency communication channels, and curated by Citizen’s team. Users who are on the scene of an incident can livestream footage, and everyone can discuss incidents in a chat box.

But its effects extend beyond the screen. Citizen likes to tout success stories, like when a user found out about a fire in his building, or when users help find missing people thanks to the app. Meanwhile, several Citizen users Quartz spoke with say they avoid certain neighborhoods because of the information they got from the app.

Citizen is how Stephanie Cortinhal, 29, found out about the 2017 terrorist attack on New York City’s West Side Highway, which was close to her workplace. She followed along on the app before any local news organizations reported the incident. Unlike many people who use Citizen, she stayed away from the area. It was frustrating that the reports on the app were fragmentary, but still, she preferred to be somewhat informed.

The flow of information from these apps can be near-constant, mirroring always-on information sources like cable news or Twitter. When it was available in three cities, it would send out about two million notifications a day across its users (now it’s in five locations, but the company would not disclose the volume of notifications). Nextdoor, the social network for neighborhoods, and Neighbors, the app where people share their Ring doorbell footage, also send out emergency alerts. Speed takes precedence over accuracy and verifiable context. The alerts come in with other notifications on users’ phones, allowing them to flip seamlessly between their TikTok feeds and alerts about a stabbing.

Some people join or follow local crime watches to feel safer and to be in the know. But there’s another reason for signing up. “Crime watch is community building in some ways—it offers a concrete reason for people to get to know their neighbors, which is increasingly difficult,” Lageson said. For decades, people have been turning away from community life.

And, with the internet, becoming part of a crime watch is almost effortless. “You’re able to join from your own home, and not actually engage in person, making participation easier,” Lageson added.

Neighborhood watches, as groups of people who physically patrol neighborhoods, blossomed in the 1970s and 1980s, and declined along with dropping crime, but have persisted into this decade. (George Zimmerman, the man who killed unarmed black teenager Trayvon Martin in 2012 was a member of one such watch.) With the advent of the internet came crime watches as blogs, websites, and more recently Facebook groups, or, in other countries, WhatsApp groups.

Now, the dominant neighborhood watch is no longer a physical group of people. It’s an invisible force that reports suspicious activity with a few taps on a phone. And, often, “suspicious” people don’t know they’re being watched.

Defining safety and community

Nextdoor is all about building communities—”stronger, safer, and happier” ones, according to its website. “When I grew up I knew everyone who lived around me. And today, I know quite few unfortunately,” Sarah Friar, the company’s CEO, told Quartz.

On Nextdoor, users can post about anything neighborhood-related—whether it’s a recommendation for a local babysitter, a sales ad for their old couch, or a query about swimming lessons for a Pomeranian (a Twitter account, @thebestofnextdoor, gathers the most absurd entries). Generally, the posts tend to focus more on community life, compared to Citizen or Neighbors.

Anyone downloading the app sees the bounds of their neighborhood already specified by Nextdoor itself.

Will Pollock, 51, a Nextdoor users from Atlanta, says that overall, Nextdoor enhances his life in his neighborhood. When his house was burglarized in 2015, he received many messages of support, and found out that a neighbor’s surveillance camera was able to catch an image of the perpetrator. Another Nextdoor user Quartz spoke with found their roommate’s wallet through the app.

Though Friar says that only 5% of posts on Nextdoor are in the crime and safety section (that includes posts about potholes or fallen streetlights), she notes that, in the past, a big part of what communities stood for was people keeping an eye out for one another.

“I think today people are looking for that same [feeling of], ‘If we all look out for each other, overall our community’s going to be a safer, better place to live,'” Friar said. She noted that Nextdoor has helped find missing pets or elderly people with dementia. “It’s really important to have that kind of network of eyes and ears.”

While Nextdoor, Citizen, and Neighbors might make some people feel more connected with their neighborhoods by recreating closer-knit communities of the past, the apps also can perpetuate and facilitate xenophobic, racist, or classist behaviors that often came alongside that closeness.

Nisa Ahmad, a TV producer in LA, wrote in a 2018 post on Medium that she had quit Nextdoor after her neighbors on the app called the police on another neighbor, a black man, for being “suspicious” during his morning run in the gentrifying neighborhood. When the man asked people on the app to be more aware of the neighborhood’s diversity “because he should not be criminalized for jogging,” as Ahmad writes, another neighbor responded:“You can’t blame us for wanting to protect our community.”

The question “’Who gets to decide what safety looks like?’ and ‘Who is actually being made safe, safer?’ [are] very different questions,” said Larisa Mann, media studies professor at Temple University who focuses on surveillance.

(Designated users called “Neighborhood Leads” review content reported as having violated the site’s guidelines and vote on taking it down.)

Calling the police on a person of color results too often in unwarranted aggression from law enforcement, leading to incidents of brutality and killings. And posts on neighborhood apps, like the one Ahmad mentions, could potentially lead to similar escalation.

Crime in many US areas is at historic lows, but the barrage of notifications on these apps can create the sense that crime is increasing. (On Citizen, this is especially acute, since the app sucks up thousands of alerts from emergency scanners, creating a map of red dots of supposed danger. “Drunk Patient Hit EMT in Face,” “Large Raccoon Preventing Entry to Home” were some of those dots on my phone one recent week. After facing criticism over the issue, Citizen has redesigned its app so that the red dots and notifications are fewer and more relevant.)

Indeed, critics have claimed these apps breed a kind of paranoia.

Ed Murray, the former mayor of Seattle, spoke with blogger Erica Barnett in 2016 about Nextdoor. “Why, suddenly, when we’re having crime stats going down in the city overall, are we seeing a huge uptick in people absolutely freaked out about crime? There are some indications that the complaints about crime may be more related to social media sites than the neighborhoods that actually have crime,” he said. The areas where users were most active, according to Murray? Safe, affluent, and majority white.

Nextdoor has taken several steps to address the issue of racial profiling. Before a user reports suspicious behavior, the app now asks the person to consider why specifically they deemed someone suspicious. In comments, which are often the place in these apps where people engage in the most egregious behavior, Nextdoor implemented a “kindness model,” which prompts users with special pop-up reminders to treat others with kindness and respect. Friar says the platform has brought the instances of racial profiling “orders of magnitude lower,” but that the company will keep working to fix the problem.

But some say there is a more fundamental issue with Nextdoor: “digital redlining,” a process of creating inequalities through technology. “In resurrecting the mid-century imagination of what a community should be, Nextdoor simultaneously resurrects the mid-century community’s structure of exclusion,” writes Katie Lambright, researcher at the University of Minnesota in the journal Cultural Critique.

By strictly limiting the geographic area of a Nextdoor “neighborhood,” the platform encourages racial profiling, which comes in part “from the idea that particular types of people live in particular neighborhoods with people like themselves,” Lambright writes. The idea is that the community is a safe, private haven in a “world otherwise filled with untrustworthy strangers.”

One user told The Root about how when his African-American wife was entering his parents’ beach house in a predominantly white area of Delaware, someone immediately called the police. When the user checked Nextdoor, a neighbor declared in a post “Spook Alert,” a slur used in the area when black people are spotted.

Friar said that the platform has to impose geographical limitations—”the alternative is creating a Facebook.”

Citizen informally creates these kinds of demarcations, because it shows users where suspected crimes happen most frequently. Cortinhal said she started avoiding a social housing complex after seeing on Citizen that there were shootings in the area. Kehr said the app convinced him not to walk by an area that “seemed” to be “sketchy.” “Now I see the actual visualization of it,” he said.

Researchers worry about this trend. A cluster of red dots in one neighborhood does not necessarily mean there’s horrific danger lurking on every corner—the reports might be unfounded, or minor. Because it lacks context, a map full of red dots on the app might discourage people from entering a neighborhood, leading to its neglect and isolation from the rest of the city. It can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Defining relationships with police

Neighborhood apps have also entered into surveillance, a domain traditionally occupied by government agencies. So they try to coexist with law enforcement, and even help them. Nextdoor encourages public agencies to join the site, where they have their own pages and can post their own content. Just like Facebook, where many local police departments have a robust presence, Nextdoor serves as a medium for public service announcements, which allows law enforcement agencies to circumvent traditional media channels and shape their message on their own, while also building up goodwill in the community.

The Seattle Police Department, for example, has used the app to reconnect with the local community after it entered into an agreement with the Justice Department over officers’ brutality.

The company encourages law enforcement to interact with the community. The agencies can’t see the conversations of regular users, and can only answer under their own posts, but users in some locations have a “forward to police” feature, which lets them send police messages about worrisome events. (These could presumably include those “suspicious persons” posts that engage in racial profiling.)

But law enforcement caution citizens to avoid using Nextdoor as a way to report crimes. In locations across the country, police departments have had to tell people that they can’t see Nextdoor posts unless they’d used the special feature. Simply posting something to the app is counterproductive.

Citizen’s mission is radical transparency, meant to help repair interactions between the police and communities. For example, the company told Quartz, sometimes people might not be comfortable calling the police, but they might report on the app where a suspect threw their gun, information that might later be useful.

The company’s relationship with the police has been rocky. When the app launched in 2016 as “Vigilante,” it quickly drew criticism from the police for incentivizing users to go to crime scenes. It became more palatable to law enforcement after a rebranding, which included the new name “Citizen.”

There’s also the suggestion from the company’s backers that Citizen can be used to hold police accountable—with the app making it easier, for example, to crowdsource footage of police abuses.

Ring and the accompanying Neighbors app, on the other hand, are increasingly entwined with, and function as a tool of surveillance for law enforcement.

The company has partnered with more than 570 law enforcement agencies from around the US. It launched a special law enforcement portal through which police departments can see all the cameras in the neighborhood. Police can ask residents for footage to support their investigations directly through the portal, and they don’t need warrants to do so.

Ring and law enforcement are building these networks of surveillance together. The company gives departments free Ring cameras to distribute to citizens (which some police have used as leverage to demand footage, CNET reported, although users are supposed to be able to decide whether they want to share it on their own. Ring has emphasized it does not condone this requirement. “Customers can choose to opt out or decline any request, and law enforcement agencies have no visibility into which customers have received a request and which have opted out or declined,” the company said in a statement). Police encourage people to download the Neighbors app, effectively advertising the product, and Ring approves the promotional copy that departments send out, Vice reported.

“We are proud to have partnerships with many law enforcement agencies across the country and have taken care to design these partnerships in a way that keeps users in control,” Ring told Quartz in a statement.

In this way, corporate surveillance—Amazon, which owns Ring, already has ears in people’s homes through its Alexa smart speakers—becomes enmeshed with government surveillance. Chris Gilliard, professor at Macomb Community College and privacy scholar, finds this unsettling. The police are at least “in theory” accountable to the public, whereas corporations are not, he said.

And surveillance affects people unequally, giving more power to those who already hold it, while disenfranchising those who are powerless. In countries like the United States, minority communities have always faced more surveillance, making them disproportionately frequent targets of police abuses and punitive attitudes within the justice system. These apps seem to be a continuation of this trend through a new medium; a Vice review of 100 posts on the Neighbors app showed that the majority of “suspicious” people reported in Vice’s Brooklyn neighborhood were people of color. A group of more than 30 civil rights groups wrote a letter to authorities protesting the police-Ring partnership. “Amazon Ring partnerships with police departments threaten civil liberties, privacy and civil rights, and exist without oversight or accountability,” they write.

It’s also not clear that these apps or devices are doing its users, on the whole, much good. This ever-present surveillance “helps sort of habituate people into an idea that more surveillance is better and healthier for society,” Gilliard says. “And it’s definitely not.” (While Ring’s mission is to reduce crime, and has said installing its products slashed burglaries by 55% in a Los Angeles, an MIT Technology Review analysis has questioned the company’s data).

Tech companies, on the other hand, clearly benefit from the notion that more vigilance is better.

Nextdoor makes money by selling targeted ads—notably, the Ring camera is a commonly advertised product. This has worked so well that the company claims it tripled its revenue last year. Amazon charges for the Ring devices, along with a monthly subscription fee for recording Ring footage. Citizen, which is backed by venture capital, has not yet disclosed plans for monetization.

Neighborhood apps are weaving a complex network of surveillance, in collaboration with enforcement and users themselves.

Dara Byrne, professor and dean at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, told Quartz previously that social networks and tech companies have allowed people to “really play dress-up like a cop, in a digital culture where you can build a whole community space to talk about it, think about it, share best practices and quasi-professionalize your volunteer service around it.”

Giving people tools used by law enforcement can encourage vigilantism. On the flip side, giving police more access to surveillance creates powerful opportunities to bolster its already-significant capabilities to spy on citizens—especially when facial recognition comes into the mix. We already have minimal expectations of privacy online, and devices like the Ring camera or apps like Nextdoor extend that into physical spaces.