This week, San Francisco’s Municipal Transportation Agency (MTA) approved the once-radical step of banning personal cars on its busiest street. The unanimous vote means the city’s main boulevard, a two-mile stretch of Market Street in the heart of the city, will be open only to those willing to walk, bike, skate, scooter, or take public transit by 2025.

Today, thousands of vehicles on the street compete with buses, streetcars, and half a million pedestrians and bicyclists per day (too often to fatal effect). For San Francisco, the $604 million project is likely just the beginning. “This is about the kind of city we want to be,” tweeted Amanda Eaken, an MTA director who supported the measure. “Let’s make sure this is just the beginning of creating more car-free spaces in San Francisco.”

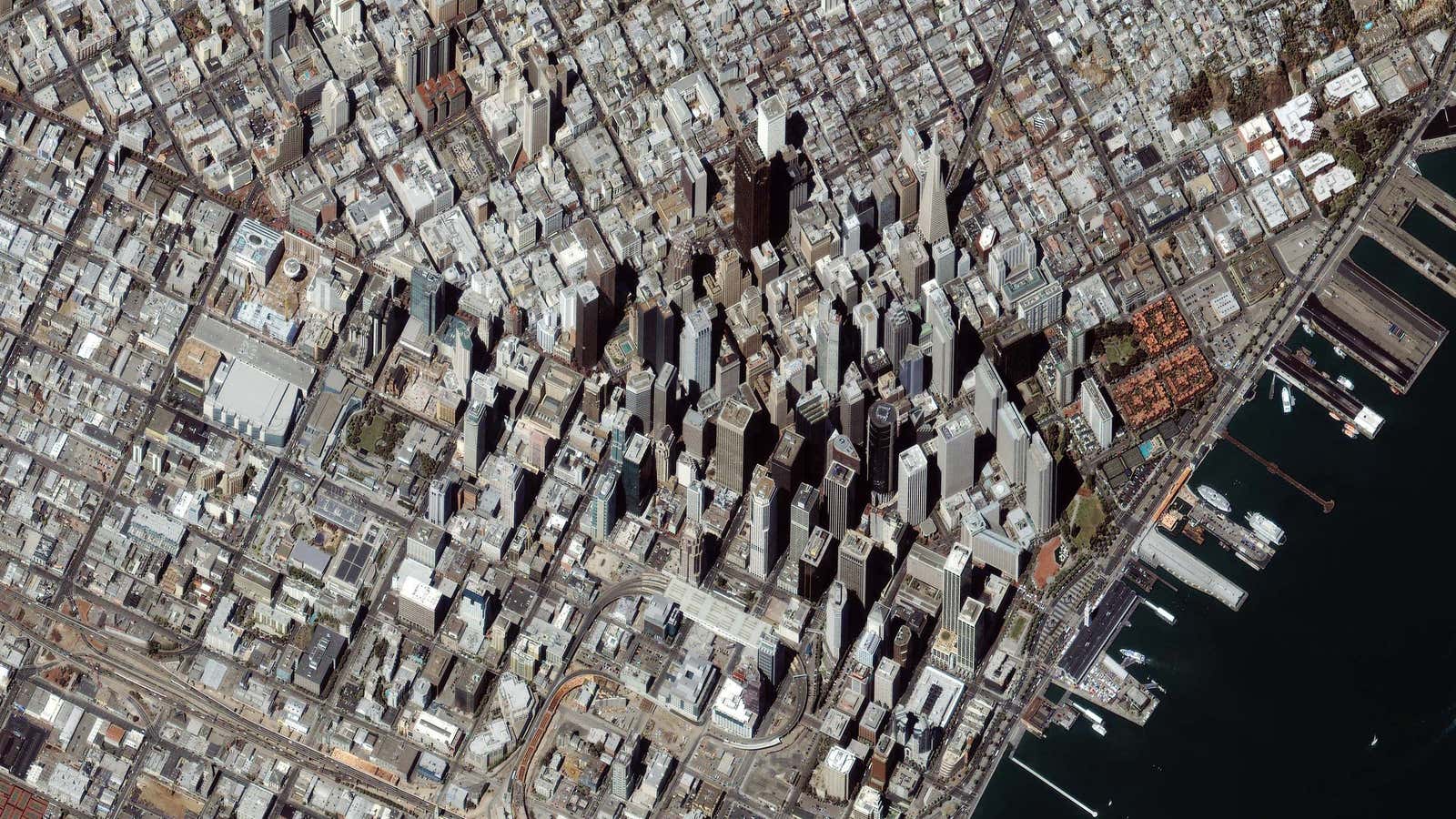

The world’s modern cities were built to suit personal cars. In the 20th century, neighborhoods were cleared and streets widened to serve streams of vehicles, often coming from suburbs. That’s starting to change. Congestion pricing introduced in London, Singapore, Stockholm, and soon New York is an interim step to remove traffic from city centers. Some are now banning cars altogether.

Oslo was one of the first. It began banishing cars from its downtown in the 1970s and, in recent decades, accelerated the process of turning more car lanes and parking spots into bike lanes, parks, and benches. People and public transportation were prioritized over private cars, buttressed by large investments in transit, bike-sharing, and street redesigns over the decades. Recently, Spain declared the core of its capital Madrid an “ultra-low emissions zone,” prohibiting through-traffic, except for registered residents, and banning older gas and diesel vehicles. A similar scheme is being rolled out in Paris. In North America, Toronto’s new nearly car-free downtown avenues have seen transit ridership soar.

The process in the US has been slower. San Francisco’s car ban on Market Street started in 2009 when former mayor Gavin Newsom (now California governor) began restricting traffic (amid much complaining).

Such half measures weren’t enough. San Francisco has seen traffic delays rise 60% between 2010 and 2016, estimates the city’s transportation agency, as an influx of new workers and ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft have overwhelmed streets. In response, residents have been opting for new ways to get around. In the past four years, the number of people biking on Market Street (still one of the most dangerous for bikers and pedestrians) has grown nearly 70%, even while the population rose 3.6%, according to a fitness startup Strava, whose Strava Metro service collects one the largest aggregated and de-identified transportation datasets for cities.

All this change in our urban centers is actually nothing new. Cities are returning to what was normal for most of modern human history, says Warren Logan, the mobility policy director for the mayor’s office in Oakland, across the water from San Francisco.

“Our streets used to be trains and bikes and walking before cars, funny enough,” he wrote to Quartz. “The real question is which street will San Francisco do next? I encourage people to think less about this being a car-closure project and more of a transit, bike and pedestrian prioritizing project.”