Iran proves that lifting its ban on women in soccer stadiums is a gauge, not a win

On the afternoon of Oct. 1, 1977, I was sitting in the bleachers at Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey.

On the afternoon of Oct. 1, 1977, I was sitting in the bleachers at Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey.

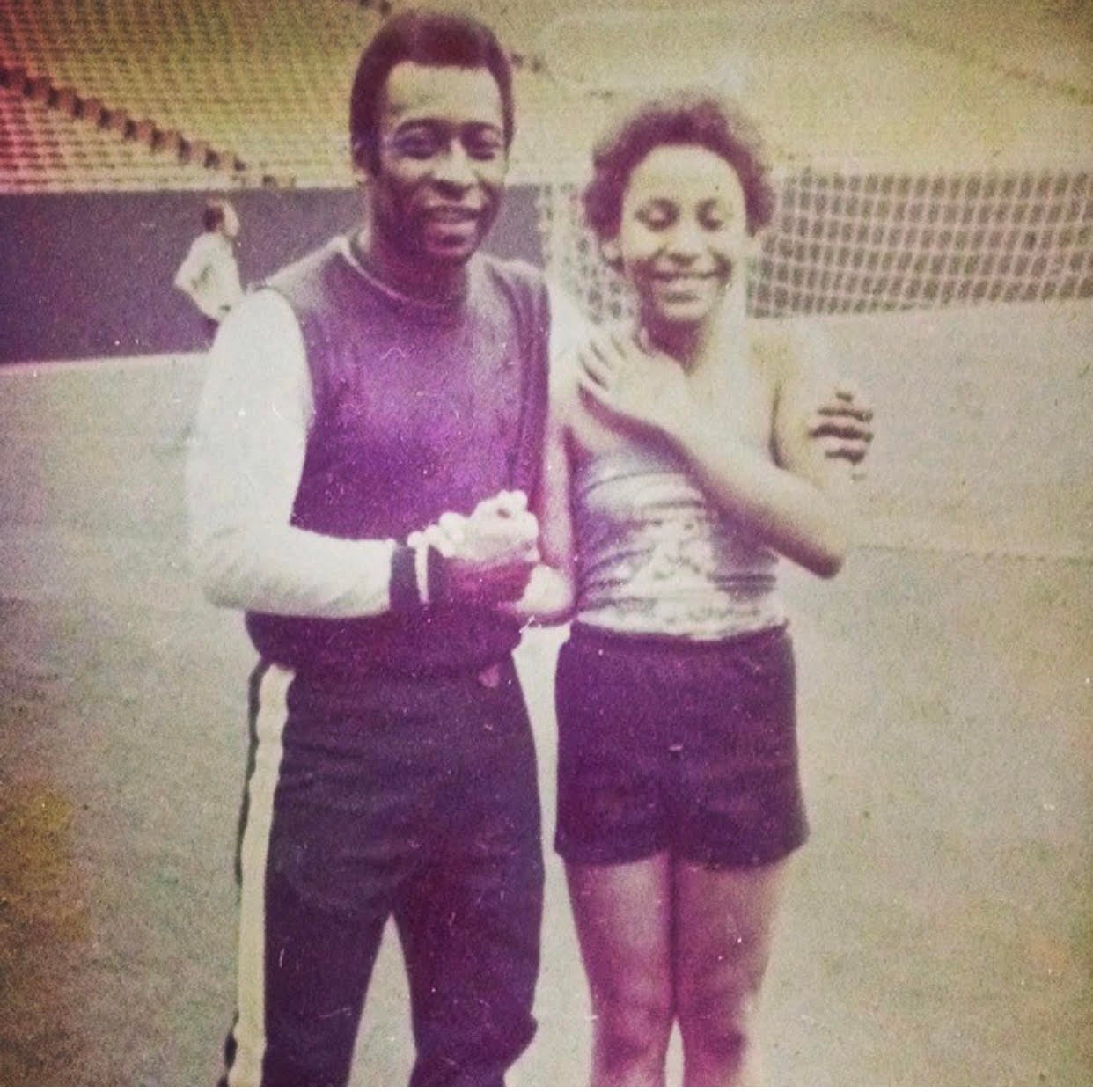

I was there with my mom, my brother, and the rest of the 77,000 women, men and children to see my father, Edson Arantes do Nascimento, who we all know as the footballer Pelé, play the final game of his career. I was 10 years old.

Here is what I remember from that day:

It began to rain during the game, so we moved from our seats, along with everyone else from the very large VIP section, and started to cram into a VIP box. Everyone was looking for cover. All I could see was a crush of elbows and buttons from my 10-year-old midriff-level vantage point.

On our way into the box, a very tall and handsome man accidentally stepped on my foot. He immediately stopped, looked at me, then bent over, apologized, and hugged me. I was later told that man was Muhammad Ali.

Even though my 10-year-old self would not have been able to verbalize it at the time, I felt an overwhelming, tangible joy, and a sense of love in the stadium that day. It felt quite literally like a hug.

Two years earlier, during the winter of 1975, my brother, mom, father, and I had moved to New York City from Santos, a small island off the coast of São Paulo, Brazil, so my father could play for the New York Cosmos.

My father had won three FIFA World Cups with the Brazilian national team and he came to the United States with the hope of inspiring this baseball- and American football-loving nation to fall in love with his “beautiful game.”

The energy from the thousands of people in Giants Stadium that day two years after we arrived is often attributed to my father and his skill and genius. But I believe the credit belongs to the unifying, healing, and transformative power of soccer, the sport most played around the world.

Our beautiful game

Today, I am a mom, an activist, and documentary filmmaker currently working on a film about women’s soccer, called Warriors of a Beautiful Game.

As part of my work, I travel the world meeting women and men and speaking about gender equality in sports. I have yet to find myself in a room of people where someone does not come up to tell me about an experience of theirs, sitting in their home stadium, or in front of a television set, when my father’s team came to play in their country.

Almost always, these stories involve a memorable and bonding family experience.

A few years ago while on a speaking trip, I had the pleasure of meeting an Iranian woman named Maryam Shojaei. I was excited to meet her because I recognized her name; her brother, Masoud Soleimani Shojaei, is one of Iran’s best players and the captain of their national team.

Maryam and I became fast friends. Like me, she grew up in a family steeped in football culture, and the pride and sense of community that comes with it.

But there were also differences. As we compared experiences, she shared with me that she could never go to the stadium to watch her brother play because it was forbidden for women to attend soccer matches in Iran.

Not only were women not allowed to be in the stadium, she told me, but this law was enforced with jail time, violence and sometimes torture. Although I had heard of Iran’s stadium ban for women, I admit I assumed it was something from the past. But Iranian women have been kept out of stadiums since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. It was hard for me to accept that Maryam wasn’t allowed to go see her brother play as I had seen my father so many times. I remember feeling so very sad for her and her family, and for all of the women and families in Iran.

That changed on Oct. 9 when Iranian authorities, ordered by FIFA, which was spurred to action following the bravery and perseverance of many Iranian women and activists like Maryam, announced women were legally allowed to enter stadiums for the first time in 40 years to attend a World Cup qualifying match between national teams for Iran and Cambodia on Oct. 10 in Tehran.

News headlines around the world celebrated the announcement. We saw images of female sports fans cheering and rejoicing as they entered the stadium the day of the match.

I believe sports provides a unique platform for women to claim power and to achieve gender equality in society. And I know we need more than this.

We should applaud Iran’s new stance. But we can’t afford to let it stop us from asking what FIFA will do to ensure the safety and inclusion of women in the future.

Equal play

Devastating as it is, Iran’s ban on women in stadiums doesn’t surprise me.

You see, there is very little in this world more unifying and empowering than the shared experience of a team sport, whether you’re a player or a spectator. With soccer being the sport most played around the world, a sport which inspires a love many liken to religion, what better way is there to divide and weaken a nation than to ensure that half its population is prohibited from participating?

Around the world, weakening the position of women and taking away their social power in a society in order to gain control over the general population is a time-tested tactic. This is no different.

Our sacrifices

Last March, a young woman named Sahar Khodayari dressed to disguise herself as a man (one way in which women in Iran have taken to protesting the stadium ban), donned a blue wig in honor of her favorite team, and made her way toward Tehran’s Azadi Stadium—the same stadium where women celebrated in October.

She never made it that far. She was arrested and taken into custody, and charged with “harming public decency” and “insulting law enforcement agents” by not wearing proper head covering, before being released on bail. On Sept. 2, Khodayari was summoned to court and sentenced to six months in prison.

Knowing what this sentence means for a woman in an Iranian prison, she left the courthouse, poured gasoline on herself, and set herself on fire.

Blue Girl, as she came to be called, died at the hospital later that week.

It is a profoundly horrific fact that it often takes an act like this to move people to take real action. In September, FIFA president Gianni Infantino released a statement declaring “women have to be allowed into football stadiums in Iran.”

With this ultimatum, the Iranian federation reportedly made 4,600 tickets available to women for the greatly anticipated World Cup qualifyer match.

Iranian authorities reported that around 3,500 tickets were sold to women fans within minutes of being made available. That’s impressive, but in a stadium that holds 78,000 people, that’s less than 5% of seats.

People expressed understandable skepticism that the move was a sham, and a symbolic gesture at best. It also prompted fears for many that the ticket sales created a very dangerous situation by putting a target on women who showed up to buy the tickets.

Aware of the potential safety risk, FIFA said it would place staff on the ground to help get women into the stadium safely.

Khodayari’s tragic death prompted action. But unless we see a real change, all these efforts were simply damage control, and don’t guarantee any change for the future of the sport in Iran. Restriction on women attending soccer matches still violates FIFA’s own constitution, and endangers women.

And allowing some women to attend soccer matches is still a ban for most women.

By making a limited amount of tickets available to women, soccer authorities essentially put a target on the women who do attend matches. Iranian authorities placed chain-link fencing around the women’s section for protection, essentially caging them in and making them vulnerable. Female photographers are still banned from covering sports events in Iran, including FIFA-sanctioned events.

The ban is still fully in place for league matches, which is where most women get arrested, and FIFA has made no arrangements for women to be allowed to attend those.

On Oct. 20, just 10 days after that hugely publicized match with some 4,600 women in attendance, the Persepolis FC team played Paykan FC at Azadi stadium with no women, no global media or cameras present.

I celebrated along with Iran’s female soccer fans on Oct. 10. But when it comes to progress, it was far from the win we need for women’s rights, especially for women in sports. Rather, it’s a grim indication of how far we have yet to go.

Iran has nominally lifted restrictions on female fans in soccer stadiums here and there over the years, but it hasn’t yet led to systemic change. The danger is that we get lost in the frenzy of one small victory, and that we let FIFA continue to give Iran’s state authorities a pass.

Iran’s football federation, like all of FIFA’s member associations around the world, receives money from FIFA. In order to continue enjoying FIFA’s systemic and monetary support, the Iranian Football Federation is subject to FIFA’s commitment to its human rights mandate in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Restricting ticket sales because of gender is in direct conflict with FIFA’s human rights policy. This includes providing a limited amount of tickets for women to purchase.

Indeed, a policy is only as meaningful as the consequences which help to enforce it. Up until this point, FIFA has chosen not to hold Iran accountable for its human rights violations. Unless there are some measures taken in response to the exclusion of women during the Oct. 20 match, it seems FIFA is going to continue to allow the Iranian federation to discriminate against women with impunity.

I cannot imagine having to sit at home with my mom on that October afternoon in 1977 as my father played his last game at Giants Stadium, while my brother got to sit in the crowd and watch. Nor my daughters and I not being allowed to sit with my husband and sons to watch Santos play at the Vila Belmiro stadium in São Paulo, a home away from home for my entire family.

Continuing to allow Iran to hold hostage the right of women to be a visible part of their culture and to use soccer as a tool to diminish and discredit women and girls besmirches the game that FIFA exists to govern and protect.

After the encouragement of Iran’s Oct. 10 match, I implore Infantino to use the power of the world’s governing body of soccer to preserve the integrity of our beautiful game.

There’s a section of the FIFA human rights mandate that says, “FIFA recognizes its obligation to uphold the inherent dignity and equal rights of everyone affected by its activities.” I want to remain hopeful that he will do the right thing.