No, soccer is not going to displace baseball as America’s national pastime, or American football as the national game, or even basketball as the country’s third most popular professional team sport.

But it’s starting to look like the “world game” might have finally found its feet in the world’s largest economy. And not just because the New York Times, in a much discussed article last month, says the sport has now become “a conversation topic you can no longer ignore.”

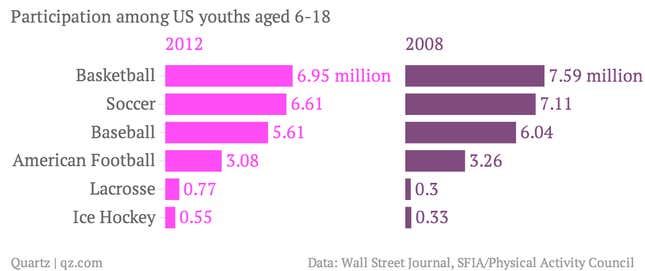

Sure, more US kids play in organized soccer teams than play baseball, according to the Wall Street Journal (paywall), but its been that way for years.

For real proof, look no further than that other great American passion: television. This year, NBC Universal has been airing English Premier League matches on its various channels (including its flagship broadcast network NBC) and ratings have been solid.

In total, 30 million viewers have tuned in for Premier League matches this season, more than double the total last year when Fox Sports had the television rights. Nine of the 10 most watched Premier League games ever took place during the current season, and matches have, on average, drawn 440,000 viewers each, compared to 221,000 last year. This Sunday (May 11), for the season finale, NBC will air all 10 matches live across its various channels.

Let’s stop to reflect on this. A foreign game, a foreign league, is being aired on US television, and people are actually watching it. This would have been unthinkable not that long ago in a nation that historically, has been very insular when it comes to its sport.

This summer, from June 12 to July 13, soccer’s centerpiece event, the World Cup, is taking place in Brazil. For the first time since the US hosted it 20 years ago, the tournament will be held in a favorable time zone for American audiences. Arguably, it’s the best chance yet for soccer to really entrench itself into the American consciousness.

A brief history of American soccer

Soccer—or football as it’s known most everywhere else—has been played on American soil since at least the late 1800s. But the sport as we know it today had its first wave of popularity in the 1920s.

This was outlined in a fascinating Slate piece four years ago in the run up to the last World Cup. In the 1920s, the US was in the midst of an enormous manufacturing boom. Waves of immigrants were arriving from Europe to work in factories, plants and mills, and they brought soccer with them. In 1921 the country’s first pro soccer competition of note, the American Soccer League (ASL), was formed; its foundation teams came from industrial towns like Fall River, Massachusetts and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Over the next decade, the league thrived. The Fall River Marksmen, for example, “drew five-figure” crowds, and (incredibly, given that soccer players earn millions today) teams were even able to lure top European talent with the promise of high-paying factory jobs. In 1930, at the inaugural World Cup in Uruguay (which was devoid of many top European teams) the US finished in third place. But by 1931, the ASL had collapsed amid bitter infighting between the league, its participant clubs, and the national federation.

Soccer basically fell off the map in the US for the next four decades. Although the US scored a memorable victory over England in the 1950 World Cup, the last time it was held in Brazil (pictured above), the sport didn’t really feature prominently again until the late 1960s, when another ill-fated professional league was formed. After securing a TV contract from CBS (but without permission from FIFA, the sport’s world governing body), a group of entrepreneurs launched the National Professional Soccer League (NPSL) in 1967. It lasted just one season. “The stadiums were empty, which made it tough for us to generate much excitement,” Bill McPhail, the former head of CBS sports, told Sports Illustrated. ”The players had foreign names, their faces were unfamiliar, their backgrounds undistinguished.”

From the ashes of the NPSL emerged the North American Soccer League (NASL), which remained semi-pro for about a decade. Then, in 1975, Pelé, the three-time World Cup winner with Brazil and arguably the greatest player in the history of the game, came out of retirement to sign with the New York Cosmos, an expansion franchise owned by the media giant Warner Communications. His contract reportedly made him the world’s best paid athlete at the time. Pelé’s presence led to unprecedented interest in soccer in the US and catapulted the sport into the mainstream.

His first match, on June 15, 1975, was aired by CBS and drew 10 million viewers,”easily a record American TV audience for soccer,” according to Sports Illustrated. US broadcasters have always struggled to embrace a sport that doesn’t stop frequently for advertising breaks and replays, and those tuning in missed Pelé’s highlights: An ad was on when he assisted for a goal and an instant replay of earlier action was on the air when he actually scored. But the hype continued to build. “The Pele machine is in full motion. If soccer doesn’t make it in this country now, the game never will,” wrote the New York Times.

The Cosmos would regularly draw capacity crowds at Giants Stadium and large crowds elsewhere around the country. The team was even forced to demand more security for Pelé after he was injured by swarming fans. “We had superstars in the United States but nothing at the level of Pele,”John O’Reilly, the Cosmos’ media spokesman, told the Guardian. “Everyone wanted to touch him, shake his hand, get a photo with him.”

Pelé retired in 1977. Then, interest in the league began to wane, just as the economy fell into a deep recession. By 1984 the NASL had folded. But 10 years later, the sport would again be back in focus when, in an inspired decision, FIFA decided to host the 1994 World Cup in the US. The tournament broke attendance records (which it still holds to this day) although many Americans remained skeptical. (“People of influence in America long believed soccer was the chosen sport of communists,” novelist Dave Eggers wrote a few years ago.)

A slow and determined effort to convince Americans to like soccer followed. After the tournament, Major League Soccer was formed. Unlike its predecessors, the league has has endured. This season’s TV ratings have been encouraging and the league’s teams look like they are finally on a stable financial footing.

In 1999, the women’s World Cup was hosted in, and won by, the US. At the 2002 tournament in South Korea and Japan, the men’s team progressed to the quarter-finals, but its matches were played in the early hours of the US morning.

In 2010 in South Africa, the US again made it through to the knockout stages, after a heart-stopping late goal by Landon Donovan in the team’s final group match against Algeria. Finally, the tournament that captures the world’s imagination every four years was beginning to get attention in America.

Peering into the future

The Brazil World Cup will carry considerable political and economic significance. Brazil, the world’s seventh-largest economy, a rising power, and a nation obsessed with futebol, will be the centre of the world’s attention.

ESPN, which—together with its sister network ABC—will broadcast the World Cup this summer to American audiences, is going all-out for the event. It will generate 290 hours of original programming across its TV channels and online, including coverage of all 64 matches, and various pre- and post-match shows. ABC, meanwhile, is sending its veteran award-winning reporter, Bob Woodruff, to cover it.

According to ESPN’s market research, 41% of Americans now identify as pro soccer fans, its marketing director, Seth Adler, said at a media event last week. More tickets have been sold for the World Cup in the US than in any other nation besides Brazil. “We can now say that the US is truly a soccer nation,” he said. “That’s not something we could have said 12 years ago.”

The network is describing its coverage of the World Cup as its “most comprehensive to date” (and ”the most complex production we have ever done at this company, bar none”). It’s not clear what to expect ratings-wise, but the press materials say it is “expected to be record-breaking.”

There is one small hitch. The US national team has been drawn in the “group of death” alongside European heavyweights Germany, Portugal (whose side features arguably the world’s best player, Cristiano Ronaldo) and Ghana, the side that knocked the US out four years ago. Progressing to the elimination stages looks almost impossible.

That means there’s a risk American audiences will lose interest quickly. But ESPN’s president, John Skipper, doesn’t think they will. “We don’t sit around with clenched fists going ‘oh my goodness, if the US doesn’t win we have a problem,'” he told reporters at the media event.

ABC will televise 10 matches, but for the first time in a long time, none of them includes US matches in the first, group stage. That means if the US doesn’t advance to elimination stages—as many expect—the national team won’t make it on to to over-the-air television during the tournament at all.

That might sound disastrous for people hoping the tournament will cement soccer’s status in the US. But it can also be taken as a sign of maturity. If America is truly going to embrace the “world game”, it must accept that it won’t always be involved.