Nokia is having one of the worst days in its history, thanks to 5G

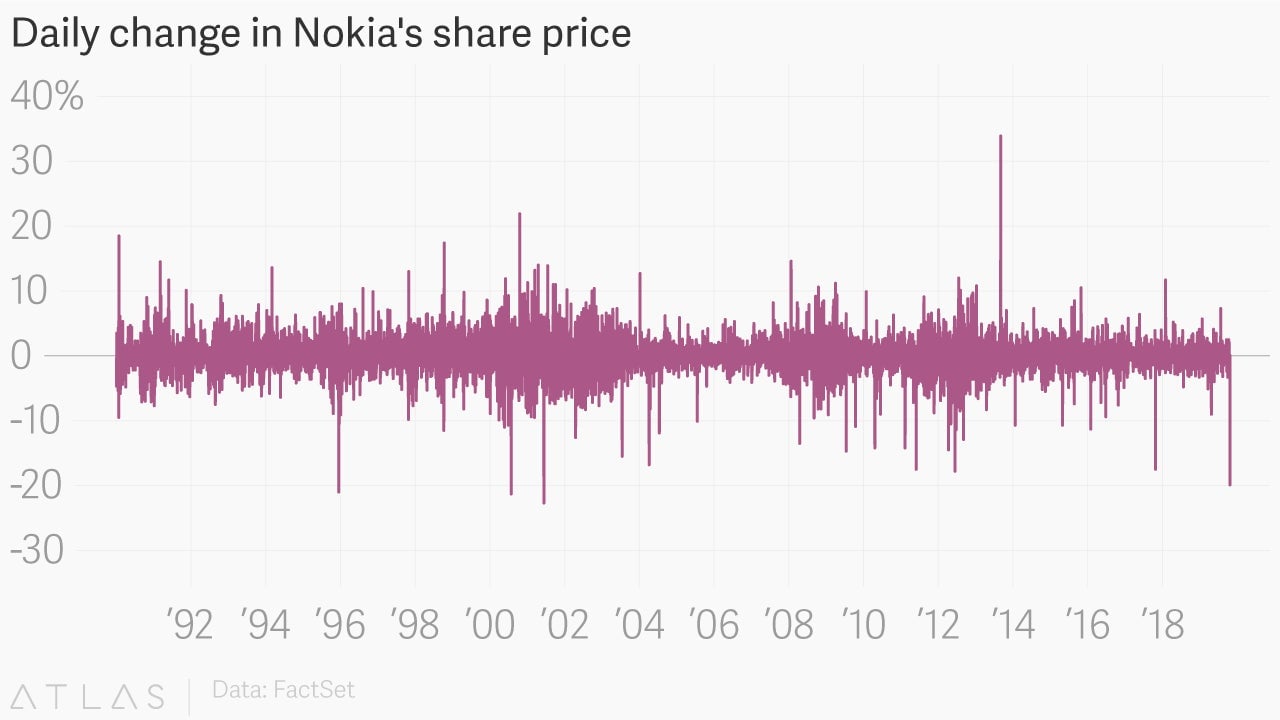

Nokia’s share price tanked by nearly 25% at one point today—the biggest daily drop since at least 1991—after the Finnish telecom equipment vendor announced a sudden and acute shrinking of its network business’ profit in its latest quarter. Slashing its profit outlook through 2020, Nokia said it would suspend its dividend for the next six months.

Nokia’s share price tanked by nearly 25% at one point today—the biggest daily drop since at least 1991—after the Finnish telecom equipment vendor announced a sudden and acute shrinking of its network business’ profit in its latest quarter. Slashing its profit outlook through 2020, Nokia said it would suspend its dividend for the next six months.

At the time of writing, Nokia’s shares were down 20% on the day, hitting a six-year low.

What’s to blame? 5G, for one.

Making fancy new equipment for 5G installations is expensive, said CEO Rajeev Suri in published remarks (pdf). He also cited trouble raising prices—especially in China, where its sales have slumped—and the expense of absorbing Alcatel-Lucent, the French telecom equipment giant Nokia bought in 2016.

The beginning buildout of 5G was supposed to be a bonanza for Nokia (see our recent field guide, “The coming 5G revolution,” for an in-depth look at this newest generation of mobile wireless network technology). What gives?

Nokia’s challenges with 5G and Alcatel-Lucent are telling, as is the cratering of its network R&D, which fell 7% versus the same quarter a year ago. Its struggles encapsulate the intrinsic mismatch of corporate oligopoly and innovation.

Though hard to tell from its glum earnings, Nokia very literally dominates the telecom equipment market. It has only two major competitors: Stockholm-based Ericsson, and Huawei, which is headquartered in Shenzhen. 1

Mind you, Huawei sells its equipment for much cheaper. And in a grab for market share, Ericsson has been discounting of late, too.

Unlike Ericsson, Nokia boasts an end-to-end suite of equipment and services. And, of course, Huawei has been sidelined from many key markets by government suspicious of possible ties to the Chinese government, and battered by US policies threatening to block its use of American technology as components in its systems.

Scale, captive customers, minimal competition—it should be a recipe for profits galore.

Dominance, however, often becomes a burden. The dynamics that at first assure easy market share and steady revenue eventually make it hard to stay profitable.

The telecom equipment industry illustrates this well. Its oligopolistic structure—reinforced by how standards bodies regulate licensing—takes pressure off the vendors to invest in broadening their technology base to compete. That’s helpful since, after all, innovating is incredibly expensive and risky.

In the short term, anyway. Because technological advances often make things cheaper to produce—and, therefore, more appealing to customers, which in Nokia’s case are telecom operators—scrimping on investment is ultimately unwise.

Of course, Nokia and its two main rivals have invested heavily in spiffy new 5G network technology, developing radically new and innovative network architecture that replaces hardware with software. But equipment is still so expensive that it threatens telecom operators’ already strained profitability, and leaves them dependent on a single vendor (which could pose security, as well as commercial, risks). That’s likely why 5G buildout has gone slower than expected.

It’s not that the equipment vendors are lazy or stingy; rather, the nature of their business means they’re stuck spending a lot in unproductive ways.

Decades of consolidation of what should be a globalized supply chain makes it hard for the telecom industry to shed old technologies. Pretty much all of the world still runs on older generations—4G, 3G, and even 2G. Telecom companies can’t just ditch those consumers, or browbeat them into buying fancier smartphones.

That means Nokia and others can’t abandon them either. Because they’re the world’s only remaining providers of the infrastructure to support legacy networks, vendors have to keep on investing in upgrading those old networks, even though the technology is outdated and those businesses are ultimately dead-ends. All of those costs are money that’s not being spent on developing new, more efficient technologies.

The competitive pressure that hit Nokia’s latest earnings should ease by 2021, Suri said. But it’s unlikely to lift entirely in the longer term. Already, operators are gunning to diversify their supplier base away from the vendor oligopoly, taking advantage of the “software-ization” of new network architecture to work with smaller vendors. Nokia’s distinctive strategy of exploiting its end-to-end offering by selling to businesses directly—a division that grew by 30% year over year last quarter—could help insulate it from increased supplier competition. It could also create another base of legacy customers to keep happy.