US Supreme Court justices talk an awful lot during oral arguments

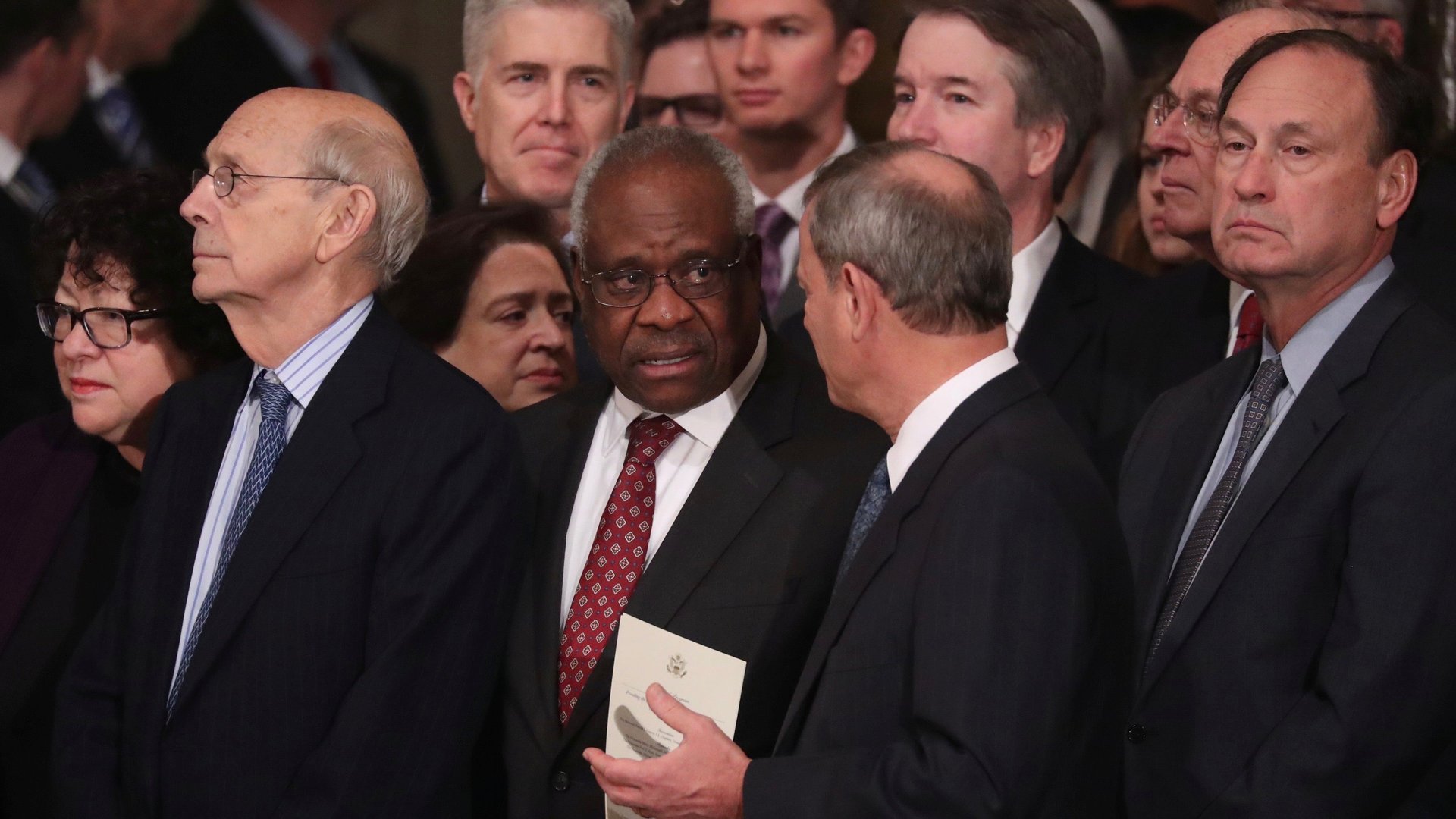

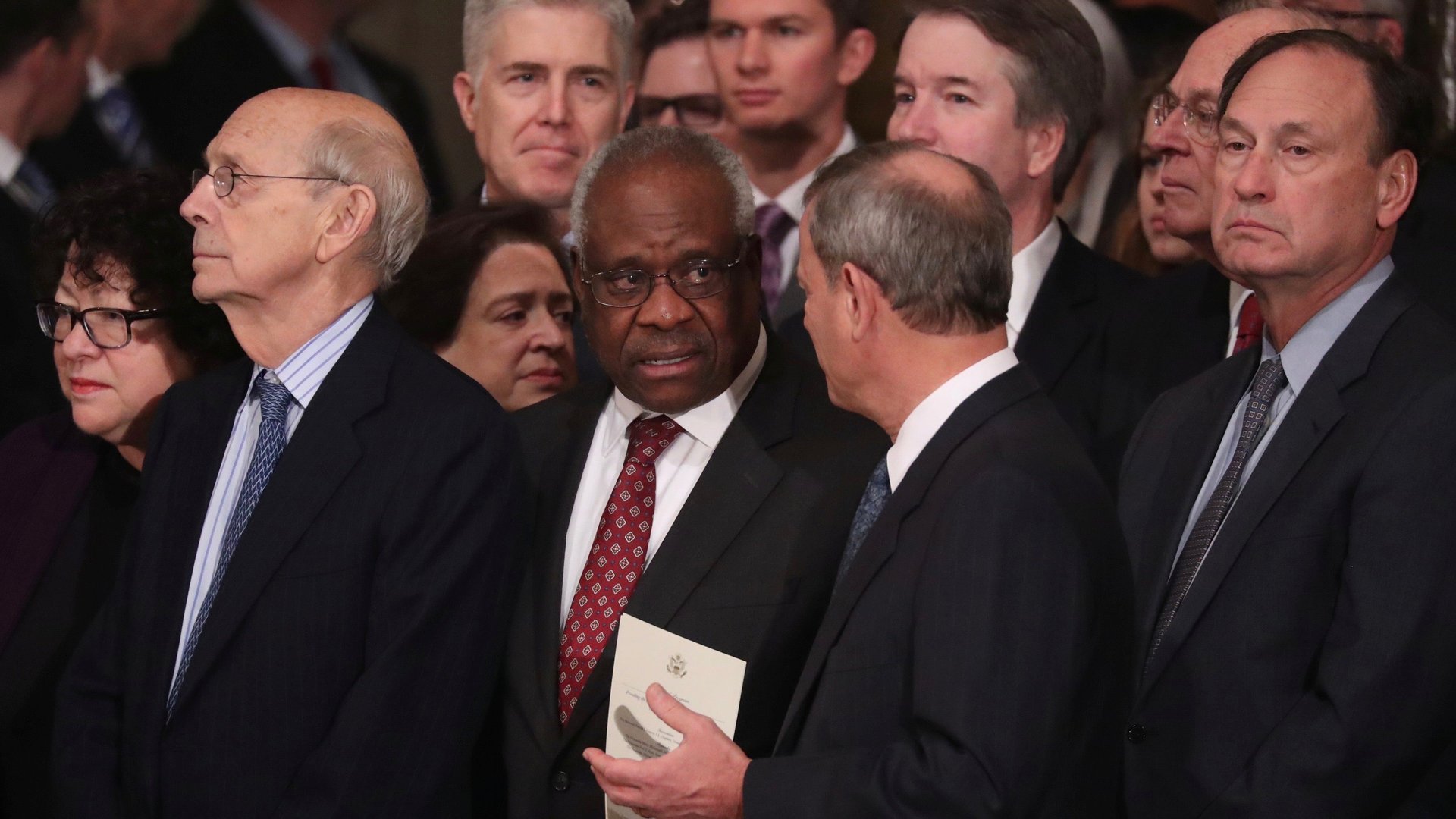

The current US Supreme Court justices are an unusually lively bunch. With the notable exception of one, Clarence Thomas, the bench is especially “hot” right now, and that’s not necessarily a good thing.

The current US Supreme Court justices are an unusually lively bunch. With the notable exception of one, Clarence Thomas, the bench is especially “hot” right now, and that’s not necessarily a good thing.

“Supreme Court Justices now speak more while the parties [at oral arguments] speak less, they interrupt both their colleagues and the parties (especially women) more frequently than in the past, and some of their questions advocate for positions rather than seek information,” explains a forthcoming paper in the Boston College Law Review by Terry Skolnik, an assistant professor of law at the University of Ottawa in Canada. “A hot bench raises crucial concerns about the nature of oral argument and appellate judges’ role in a constitutional democracy.”

The reason talkative justices are a worrisome development is that oral arguments are the only time that lawyers on an appeal get to speak. Everything else is handled in written briefs and correspondences with limited word counts. Arguments are thus a rare opportunity for an appellate attorney to tell the justices what most matters in the case before them. But to do that, the lawyers need a chance to get a word in edgewise and, of late, the justices have just been talking too much.

The court has already acknowledged the problem and instituted new measures to prevent it. For the new term, which began this month, justices began to follow newly instituted guidelines. They now have to try to keep quiet for the first two minutes of an attorney’s allotted argument time, which is usually 20 to 30 minutes. “The Court generally will not question lead counsel…during the first two minutes of argument,” explains a booklet issued by the high court to guide arguing attorneys. “The white light on the lectern will illuminate briefly at the end of this period to signal the start of questioning.”

If this concession doesn’t seem like much, consider the fact that last term, one attorney was interrupted 11 seconds into his time, by justice Sonia Sotomayor. He said one sentence before the justice began questioning him. And she was not the only one hot to talk. As Empirical SCOTUS notes, “there were 33 instances last term where…counsel spoke for 30 seconds or less to open an argument before a justice began with questions.” Over the whole term, the average amount of speaking time for introductory remarks was slightly more than 54 seconds.

Some of the justices are more inclined to jump in than others, however. Sotomayor was most likely to ask the first question last term, and the average speaking time she gave attorneys before interrupting their introductions was 39 seconds. The chief justice, John Roberts, was also pretty quick on the draw, jumping in after 49 seconds on average when he asked the first question, although he did so far less often than Sotomayor.

For justice Thomas, his colleagues’ eagerness to speak at oral arguments has long been a source of consternation. Thomas is famously silent at hearings and the occasions when he engages attorneys, rather than listening, are so rare as to make headlines. In June, when asked at an event at the Supreme Court Historical Society whether justices should be querying more, Thomas objected humorously, pleading, “Oh God, no, don’t say that.”

Jokes aside, Thomas may be right to express concern. As Skolnik notes, justices are supposed to present at least the appearance of objectivity. Using oral arguments to state their positions undermines that sense of fairness people rely on, the law professor argues.

Practically speaking, there are consequences to this questioning for parties. The proportion of questions asked ends up affecting outcomes, and more isn’t better in this situation. “The party who is asked the most questions is least likely to win their case,” Skolnik writes. “For that reason, Chief Justice Roberts [has] remarked that ‘the secret to successful advocacy is simply to get the Court to ask your opponent more questions.’”