The three things that make British elections so different from American ones

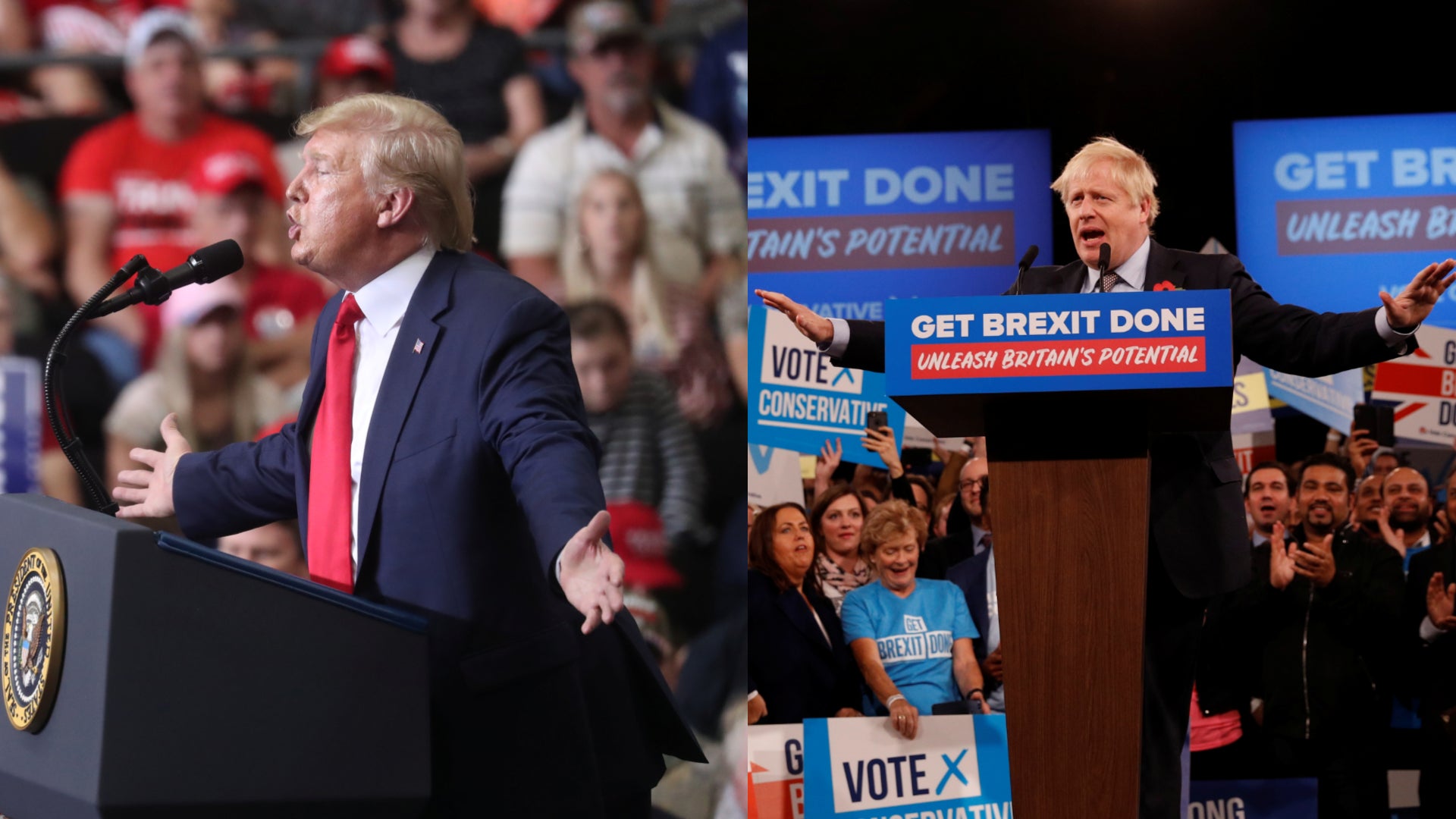

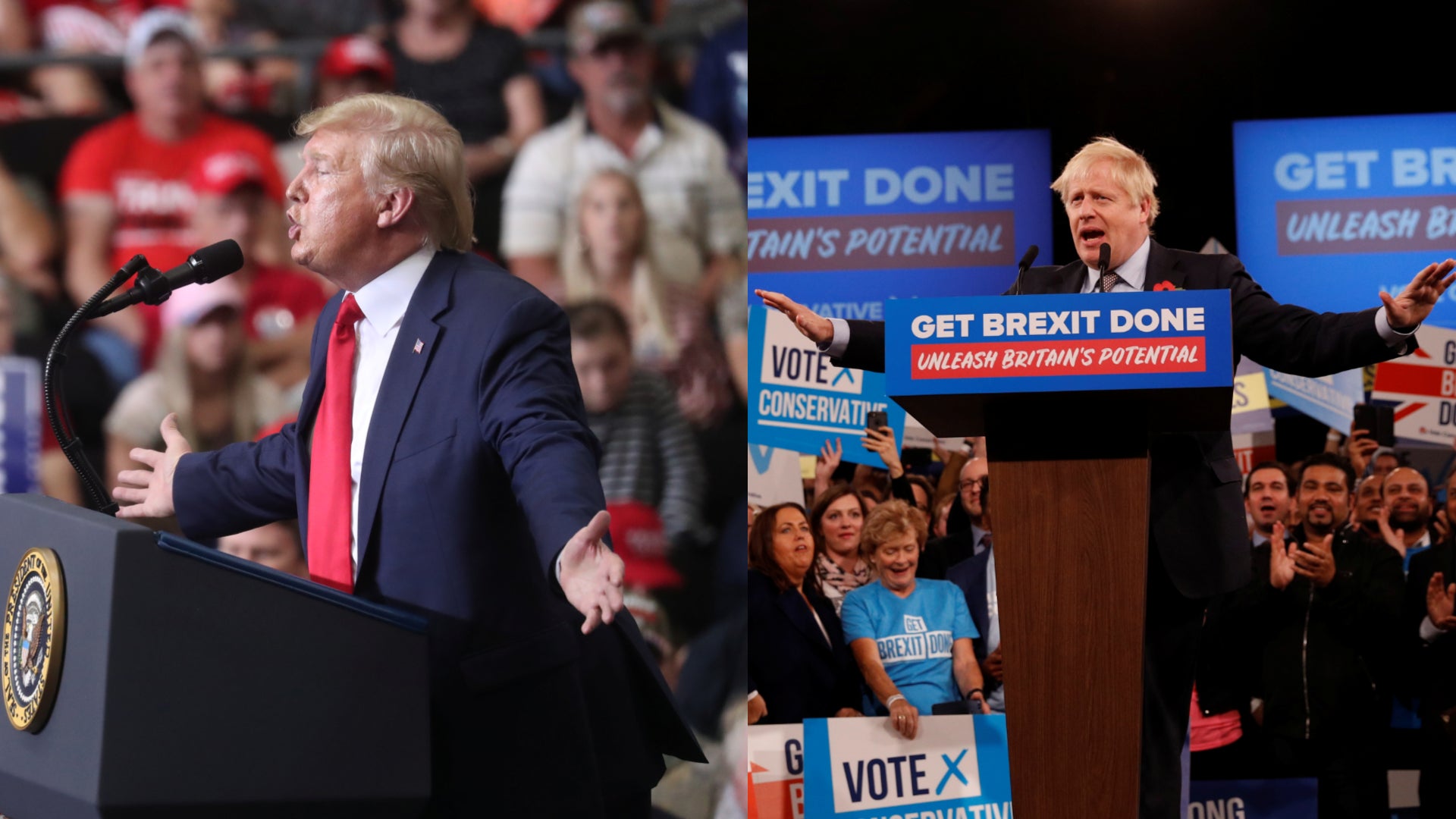

Yesterday, British prime minister Boris Johnson went to Buckingham Palace to ask Queen Elizabeth II to dissolve Parliament, protocol ahead of a general election scheduled for December 12th. That sort of pageantry is just one way that the US and UK election campaigns differ.

Yesterday, British prime minister Boris Johnson went to Buckingham Palace to ask Queen Elizabeth II to dissolve Parliament, protocol ahead of a general election scheduled for December 12th. That sort of pageantry is just one way that the US and UK election campaigns differ.

There are three major ways that British elections differ from American ones, making the process scarcely recognizable to voters on opposite sides of the Atlantic.

Money in politics

The first, and most important, is money.

In the UK, there are no limits on how much individuals and groups can contribute to candidates or parties. There are, however, strict limits on what candidates and parties can spend.

In the year before an election, political parties running candidates in Great Britain’s 632 constituencies (which excludes the 18 seats in Northern Ireland) can spend about £19 million ($24 million) each. Candidates themselves can spend based on how many electors there are in a constituency and whether they are urban or rural (they can spend more to reach rural voters). On average, candidates spend about £15,000 during the campaign, according to Justin Fisher, a professor of political science at Brunel University.

During the campaign for the UK’s 2017 general election, political parties, candidates, and non-party campaigners spent around £40 million. In the 2016 US election, presidential candidates, Senate and House candidates, political parties, and outside interest groups spent a whopping $6.5 billion trying to influence federal elections.

“There is no comparison to the amount that can be spent in US politics,” Fisher said. “The problem with British politics is there’s too little money. The problem with American politics is there’s too much.”

The UK’s strict spending limits means there is less incentive to give to parties and candidates, so they raise far less money than in the US. Third-party political groups, what might be classified as political action committees (PACs) in the US, are not major players, with Fisher calling their spend “relatively modest.” Also, money that a British party spends campaigning for the European Parliament elections, local elections, or by-elections counts towards their spending limit in a general election.

The parties also operate very differently. “British parties are effectively year-round, in and out of election-year organizations in a way American parties aren’t,” said Samuel Power, a lecturer at the University of Sussex.

For example, the Labour Party raised £56 million in 2017, but spent only £11 million on the election, Power said. The Conservatives raised £46 million and spent £18 million on the election that year. In the US 2016 election, the Democratic party raised $1.3 billion, most of which it spent. Ditto the Republicans, who raised $969 million and spent $934 million.

Fisher says the vast differences in money spent stem from contrasting philosophical approaches: the US favors liberty—the freedom of expression, which includes financial donations—while the UK favors equality. “Most European elections, and the UK is an example of this, are based on the principle of equality, of trying to ensure that the spending does not unduly advantage one side or another,” he explained.

In the US, individual donors can give $2,800 per candidate for primary and general elections, and more for parties, committees, and other politically active groups. According to Paul Waldman at the Prospect, this is “the worst of both worlds.” The lack of spending limits mean candidates always fear being outspent, but they can only raise money from individual donors in relative small increments, so “they have to keep asking and asking and asking.”

In the US, with the presidential race still one year away, candidates have already raised $624 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

The media’s role in elections

The second big difference between US and UK elections, and the most noticeable for anyone who has lived in both places, is Britain’s ban on political advertising on commercial television and radio. The parties are instead given free time to screen short pre-election broadcasts on television.

There is also the quirk of “purdah,” a term that derives from a practice in some Muslim and Hindu societies of screening women from men or strangers, especially by means of a curtain. In election parlance, it refers to the period between the time an election is announced and the election itself, during which the civil service and government officials are heavily restricted in what they can say and do in an effort to not give the incumbent party an advantage.

Political advertising is a key part of what makes US campaigns such a massive money pit. As Maggie Koerth-Baker reports in FiveThirtyEight, in 2012 ads made up more than 70% of Barack Obama’s campaign expenses and 55% of Mitt Romney’s; in 2012 and 2014, the average Senate campaign spent 43% of its budget on ads and the average House campaign spent 33%. American candidates spend so much on ads because they work: “For House seats, more than 90 percent of candidates who spend the most win,” writes Koerth-Baker.

Another big difference in media rules is that UK broadcasters are required by law to give equal time to all the major parties, attempting to balance time spent reporting on Conservative prime minister Boris Johnson with stories and responses from Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, for example.

In the US, it’s essentially a popularity contest. According to data from tracking firm mediaQuant, Trump got $5.6 billion in “free earned media” coverage during his campaign, more than all of his Republican and Democratic rivals combined.

These strict rules in the UK are breaking down when it comes to social media advertising. Parties don’t have to have include an imprint on such ads as they do in printed material, stating where it came from. Parties have been spending more and more in online advertising, which is considerably less regulated than TV, radio, and print.

The length of campaigns

The third major difference is the time devoted to campaigns.

In the UK, elections are far shorter than the US. The last US presidential campaign lasted nearly 600 days—roughly speaking, forever—as measured from when the first candidate, Ted Cruz, announced his run. The official campaign period in the UK is 25 working days, or roughly five weeks.