The trends that may end the “y’all” vs “you guys” debate

English speakers have been deprived of a truly functional, second person plural pronoun since we let “ye” fade away a few hundred years ago.

English speakers have been deprived of a truly functional, second person plural pronoun since we let “ye” fade away a few hundred years ago.

“You” may address one person or a bunch, but it can be imprecise and unsatisfying. “You all”—as in “I’m talking to you all,” or “Hey, you all!”—sounds wordy and stilted. “You folks” or “you gang” both feel self-conscious. Several more economical micro-regional varieties (youz, yinz) exist, but they lack wide appeal.

In reality, only two alternatives to the vague plural “you” disappear into American conversations without friction: “y’all” and “you guys.”

But here’s what’s hard to explain: The first, a gender-neutral option, mainly thrives in the American South and hasn’t been able to steal much linguistic market share outside of its native habitat. The second, an undeniable reference to a group of men, is the default everywhere else, even when the “guys” in question are women, or when the speaker is communicating to a mixed gender group.

“You guys,” rolls off the tongues of avowed feminists every day, as if everyone has agreed to let one androcentric pronoun pass, while others (the generic “he” or “men” as stand-ins for all people) belong to the before-we-knew-better past.

So why is this is happening now, when we have largely come to accept that language can change the way you perceive the world? And when most would agree that, as the University of North Carolina sociology professor Sherryl Kleinman wrote in a powerful essay published in 2002, the use of universal male pronoun is “another indicator—and, more importantly, a reinforcer—of a system in which ‘man’ in the abstract and men in the flesh are privileged over women?”

And especially when, as Christine Mallinson, a professor of language, literacy, and culture at The University of Maryland, Baltimore County, points out, “y’all” is sitting right there, offering us a lovely, ready-made solution to avoid calling everyone men?

Indeed, Mallinson has a couple of theories about the pronoun’s failure to take hold nationally or internationally. However, the professor, who has spent 20 years studying varieties of English, including Southern US English and Appalachian English, also believes that more people are beginning to see “you guys” as problematic for women, and for the gender nonconforming and trans communities, just as Southern culture is gaining cachet.

It may be time to get excited, y’all.

We’re out of excuses for “you guys”

In fairness, Mallinson is still willing to cut many people slack for uttering “you guys.” The pronoun may be a curiosity, or an insidious annoyance, for academics, she says, but they are a niche group. For most others, pronouns fly under the radar. We repeat what we hear in the “linguistic ether,” says Mallinson, without much thought. And because we choose pronouns so automatically, it can be hard to change habits, even with strenuous mental effort, as those now incorporating the singular “they” may have discovered.

For all the same reasons, however, doing the work to adopt new pronoun customs sends a strong message about one’s personal or cultural beliefs, Mallinson explains. So if someone values language that supports equality, but is unwilling to back away from “you guys,” they probably should be able to explain why. This is where this debate can get into sensitive territory.

One common defense of “you guys” that Mallinson encounters in the classroom and elsewhere is that it is gender neutral, simply because we use it that way. This argument also appeared in the New Yorker recently, in a column about a new book, The Life of Guy: Guy Fawkes, the Gunpowder Plot, and the Unlikely History of an Indispensable Word by writer and educator Allan Metcalf.

“Guy” grew out of the British practice of burning effigies of the Catholic rebel Guy Fawkes, Metcalf explains in the book. The flaming likenesses, first paraded in the early 1600s, came to be called “guys,” which evolved to mean a group of male lowlifes, he wrote in a recent story for Time. Then, by the 18th century, “guys” simply meant “men” without any pejorative connotations. By the 1930s, according to the Washington Post, Americans had made the leap to calling all persons “guys.” Some experts argue that the way we speak to each other on Twitter and other social media sites—with a detached, casual tone— has contributed to more recent meteoric rise in “you guys” in conversation, the Post also explains.

But, Mallinson argues, “guy” is a gendered word in any context.“You know, if I referred to you as ‘Lila, that guy,’ you would probably point out that was not accurate,” she tells me. Simply calling it gender-neutral because we use it that way is not a great rationale,” she adds. As her recent research into the history of feminist linguistic activism reveals, the exact same reasoning had been used to justify the generic “he,” until the women’s movement pushed the topic to the foreground in the 1960s and 1970s.

Another common complaint about “y’all” is that it’s weighted with very specific cultural and geographical significance, she has found. People from outside of the South don’t want to appropriate another group’s language. (Full disclosure: As a Canadian, I confessed to Mallinson that I couldn’t imagine adopting “y’all,” because I would feel like an imposter.)

Mallinson has some sympathy for such hesitation. “People are very sensitive to wanting to make sure that they use language in ways that feel authentic to them,” she acknowledges, and we expect others to do the same. Note how we still haven’t accepted Madonna’s British inflection, which the Michigan native acquired when she moved overseas more than 20 years ago, she says.

Still, we might be able to get past this awkwardness by changing our mindset. Let’s see “y’all” as a feature of American English, she proposes, and a useful one at that. It’s not as though we haven’t adopted words from outside our own linguistic villages before. See “cool” says Mallinson, which once belonged exclusively to the Black American dialect, as just one particularly longstanding example.

Finally, we get to an uglier, perhaps more obvious truth: The biggest obstacle to “y’all” going national or international, Mallinson and others contend, may be biases against the South and Southerners. All the negative stereotypes about the region—that it’s backwards, or that its people are sexist, racist, unsophisticated, and undereducated—get “mapped on to ‘y’all,'” Mallinson finds. Consciously or unconsciously, non-Southerners may be letting prejudice keep them from accepting the obviously superior pronoun.

Granted, if “y’all” were used exclusively by a vile subculture, one could understand the urge to quarantine it. However, that’s not the case. Mallinson points to research from the University of Texas at San Antonio and Oklahoma State University, published in 2000, that shows “y’all” is used by 85% of Southerners, meaning it is spoken within every demographic and by people of every political stripe.

In areas outside the South, about 50% of Americans say “y’all,” too, the same research found. And though primarily associated with the South, “y’all” is also strongly linked with Black American culture. (Parsing how much that has to do with “y’all”’s Southern origins might not possible, says Mallinson, since the histories and migrations of US dialects are tightly intertwined.)

In short, if “y’all” were a political candidate, it would have a wide and sturdy base, but it would still have an electability problem.

The South is rising

Recently, an acquaintance of mine was pretty blunt about her reason for not wanting to take up “y’all” instead of “you guys,” when I raised the topic. “When I hear someone say ‘y’all,’ I think they sound stupid,” this native New Yorker said, proving Mallinson’s point. At the same time, she was not offended to be one of “the guys” when addressed that way, she insisted.

Her reaction epitomized what’s so curious about “y’all” versus “you guys,” and why things may be about to change. Americans are in the midst of some deep soul-searching about the divisions in their country, and what it means to make space for all groups and identities, without exception. “Y’all,” with its gender-agnostic friendliness, does just that.

The South appears to be shedding some of its stigma, but for reasons that have nothing to do with politics. “Southern cultural exports are having an ever-stronger influence on American culture more generally, and the question might even be asked whether products such as country music, soul food, and even country accents are even remarkably Southern anymore,” Mallinson writes in a chapter of The Routledge History of the American South.

Another way we know the South is rising in the national consciousness, besides the recent explosion of interest in country singer Dolly Parton? Consider the arrival of the Yee-Haw Agenda.

Despite its title, this trend is largely about aesthetics, namely, “the surge of progressive Southern, country, and cowboy styles crossing from the fringe (no pun intended) into the mainstream,” says Texas Monthly. It’s about embracing western fashions and coincides with renewed interest in celebrating the erased history of Black cowboys and Black country western music in America.

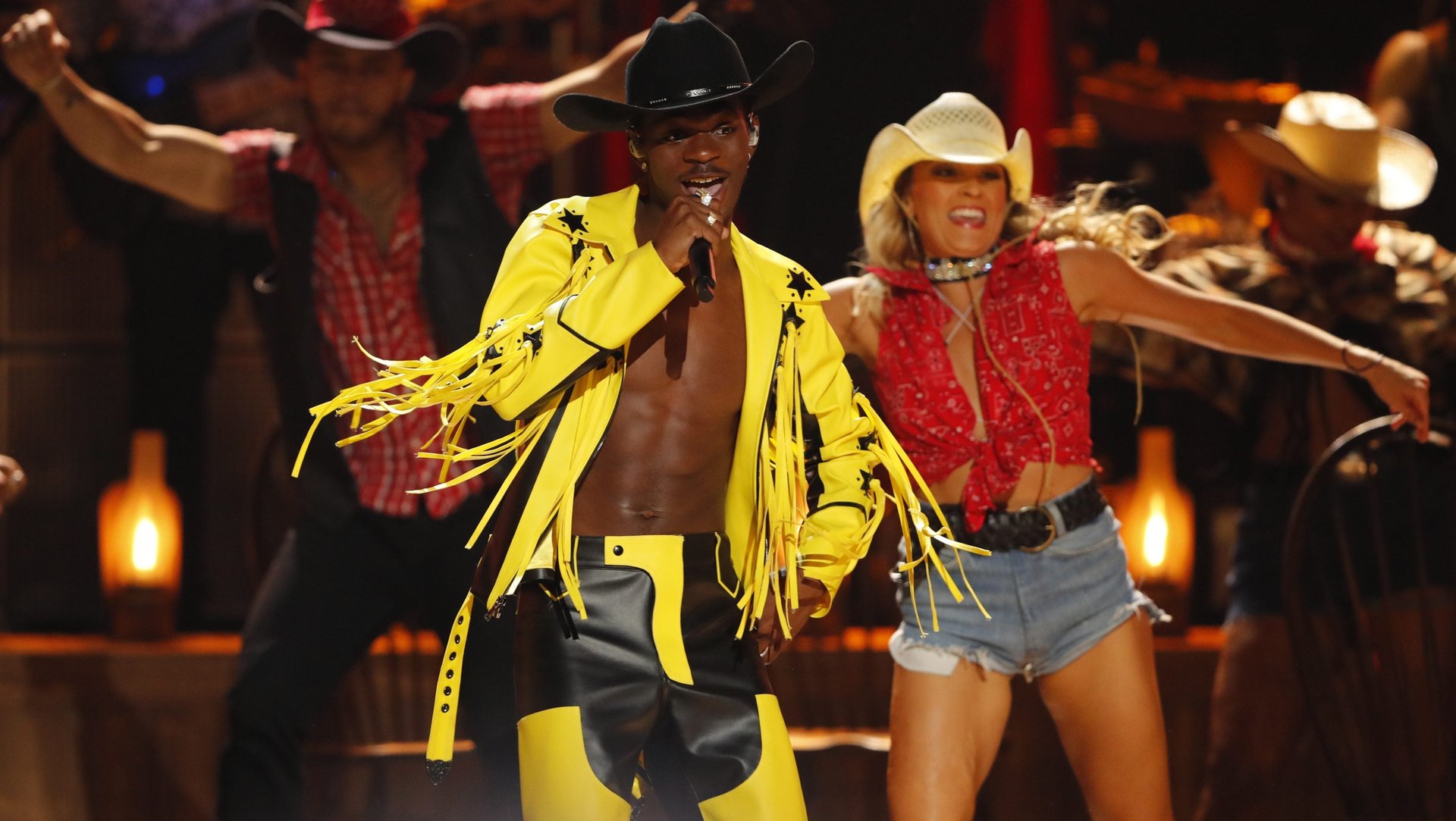

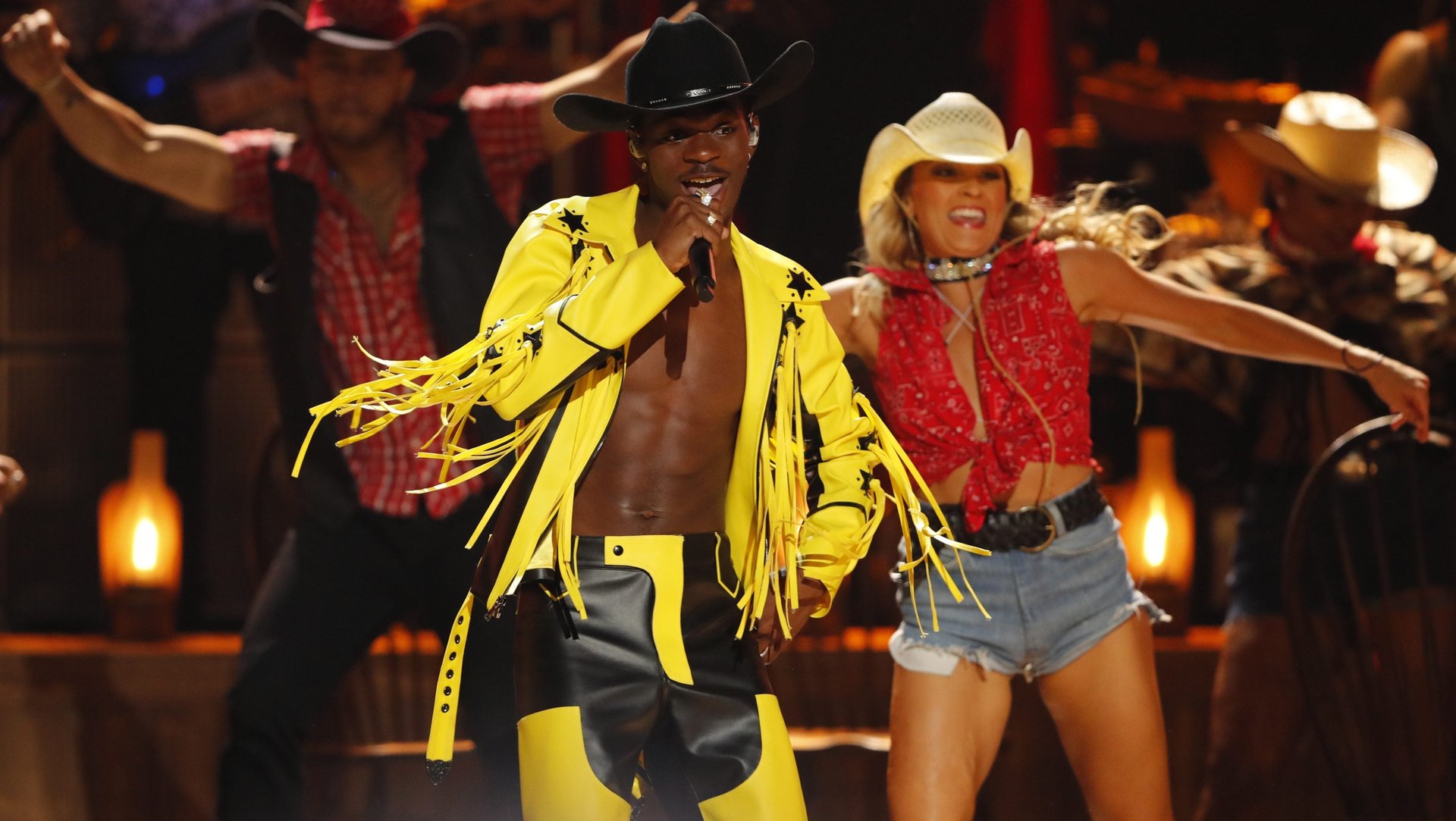

Several musicians, including Solange and Cardi B, have at times represented the Yee-Haw Agenda this year, Rolling Stone reports, but Lil Nas X, with his blockbuster country-trap song “Old Town Road,” is the most prominent face of the movement. As it happens, in a recent defining cultural moment, when Lil Nas X hinted at his sexual orientation before later confirming that he was gay, “y’all” was front and center:

Mallinson is hopeful, too, that the more individuals, organizations, or governments continue to examine language for gendered messages, whether to prevent discrimination in the toy aisle or to accept gender as a spectrum, the more “y’all” stands a chance of being accepted by the masses. “People think about language as being a superficial thing,” she says, “but the #MeToo movement proves that a hashtag can be a marker of a major social movement.” With the words we choose, she adds, we can all play a role in such broad changes.

How do language norms change?

Still, what happens next for “y’all” is, in reality, anyone’s guess.

Researchers from the Universitat de Barcelona and the University of London recently investigated how one variant of language “wins” out over another when the two compete for validation. Their study, published in Science in 2018, used experiments with more than 100 participants to test whether a small group of actors hired by the researchers could overturn a linguistic norm in a computer game that required several people to form a consensus on a naming convention in order to claim victory.

Andrea Baronchelli, one of the authors of the paper, tells Quartz that the results supported the critical mass theory, which says that social movements can begin to effect change once they’ve accumulated a certain percentage of supporters, even when that number remains a relative minority. “Depending on the model you use, that figure can range between 10% and 30%,” says Baronchelli. Their experiments found that when 25% of a given population were “committed agents” purposely working on instituting a new norm, it was enough to bring about a “global” change within that group.

A committed agent, Baronchelli further explains, is someone who uses the variation of choice exclusively, without being influenced by the environment or social contagion, says Baronchelli, and even makes a point of talking about their linguistic choice when they hear someone make what their convictions tell them is the “wrong” one. Uncommitted agents, by contrast, might flip back and forth between the variants and wouldn’t press the issue in a conversation.

He cautions that his research used specific examples and the conclusions may not be universal. However, in the case of “y’all,” one could imagine one that despite its considerable popularity outside the South, it has yet to get as much traction as”you guys” because not enough people have advocated on “y’all”‘s behalf. It needs activists. Yet, exactly how you build a committed minority group in the name of social change is still a million-dollar question, says Baronchelli. Theories exist, he says, but “as humans don’t have an answer to that.”

We do know what has worked for linguistic activists in the past. Mallinson points to the story of “Ms.,” for instance, which rescued women from needing to identify their marital status with Miss or Mrs, fairly recently. “Ms.,” coined in 1901, was revived in the 1960s by a “one-woman lobbying force,” as the New York Times called the civil rights worker Sheila Michaels. But it didn’t really go supernova until it was championed by celebrity feminist Gloria Steinem, who started Ms. Magazine in 1971.

Note, however, that Steinem explicitly spoke about the honorific “Ms.” in interviews; she was a “committed agent,” if you will. “If somebody who is really popular at the moment started talking about why [“y’all”] was important to them, I think people might take notice,” says Mallinson. Maybe there’d be some jokes or mocking of “y’all,” but the net effect might still be beneficial, she believes.

Consumer corporations could “lead the way,” says Mallinson, as they continue to see the commercial value of inclusive language. And online social media, or memes, might be able to play a role. Dictionaries or copy editors at major newspaper would eventually catch up as lagging indicators of the language norms already widely used. (It wasn’t until the late 1980s when the New York Times added Ms. to its stylebook.)

Then there’s the lesson from Sweden, where the gender-neutral third-person pronoun “hen” is used in court rulings, the media, and books, according to The Guardian, even though it was only coined in the 1960s. At that time, a linguistics professor wrote a newspaper op-ed introducing the gender-blind word, proposing it be used when gender is irrelevant and to avoid Sweden’s version of the construction “he or she,” han or hon.

In the beginning, “hen,” which had been adopted by Sweden’s transgender community in the 1990s, sparked a backlash when it went mainstream. Somewhat impossibly, the apparent tipping point for “hen” was the publication of an extraordinarily popular children’s book called Kivi & Monsterhund, published in 2012. Nevertheless, it’s now widely understood and surprisingly commonplace: at least one study suggests it may even be changing the way people people see gender and LGBTQ identities.

Perhaps “y’all”—which isn’t even a neologism and thus should be easier to install—needs some help from kids’ lit? Or, the kinds of parents who bought that Swedish book and who sent their children to gender-neutral kindergartens?

Alternatively, maybe “y’all” can hitch a ride on the star that is the singular “they”, which has gained serious traction in the last few years. “It could if people who care about these issues are linking the two of them together in their minds or in their linguistic practices,” Mallinson muses.

Again, it’s all speculation. But at least it’s clear that “y’all” is in a solid place at the right moment in history to make “you guys” vanish. It just needs y’all to engage.