The life-changing magic of the lucrative transformation economy

Twenty years ago, B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore coined the term “the experience economy” in their seminal article in Harvard Business Review and soon-to-be-reissued book of the same title. Pine and Gilmore wrote about how over centuries, consumers’ dollars—and workers’ hours—have shifted from commodities, to goods, then to services, and finally to experiences.

Twenty years ago, B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore coined the term “the experience economy” in their seminal article in Harvard Business Review and soon-to-be-reissued book of the same title. Pine and Gilmore wrote about how over centuries, consumers’ dollars—and workers’ hours—have shifted from commodities, to goods, then to services, and finally to experiences.

Consider the coffee bean. As a commodity, it fetches a uniform price on the market—$1.04 per pound, at the time of writing—or a few cents per cup. As a good—that is, after coffee beans are processed via roasting, grinding, and packaging—they’re worth more. Coffee becomes a service when someone else, say, a guy at a convenience store, brews that coffee for you. That’s even more valuable to consumers, worth maybe a couple of dollars. And when coffee becomes an experience—picture your favorite café, where the music is always good, the lighting is just so, and the barista remembers your order—it’s an experience, worth at least another dollar.

But what if that coffee is life-changing? What if, as is the promise of the Seattle-based Bulletproof Coffee—which is essentially coffee made with butter—it has the power to create a desired outcome in the consumer, to help them biohack to a happier, smarter, better-rested state of being? And what if you become a Bulletproof acolyte as a result, reading Bulletproof books, listening to the Bulletproof Radio podcast, and paying to attend Bulletproof biohacking conferences?

Then, that coffee has evolved to become part of what Pine and Gilmore call the transformation economy, where the product is not actually a $5.25 cup of “certified clean coffee blended with Brain Octane Oil and grass-fed butter” at all.

The product is a new and improved … you. And for that, Bulletproof and other players in the transformation economy are betting, you are probably willing to pay even more.

Welcome to the transformation economy

“Any company that says it wants to help make you healthy, wealthy, or wise is really in the transformation business,” says Pine. “Consumers are increasingly paying people to help them achieve their own aspirations.”

The transformation economy includes high-end retreats, coaches, gurus, and guides that promise a personal transformation, whether physical, professional, mental, or spiritual. (Or sometimes, all of the above.)

We can see this shift reflected in the decline of old-school status signifiers: High-end leggings and local, organic foods that imply an investment in one’s well-being and environment are more impressive than stilettos and imported champagne and caviar. When it comes to travel, forget wine-tasting in Bordeaux; go take ayahuasca in Peru. Come home transformed.

Because the transformation economy is a relatively new phenomenon, and one that includes aspects of various sectors, data about its size and rate of growth aren’t readily available. But there are indicators that can help quantify its rise.

Pine points to industries such as healthcare, wellness, and fitness as natural parts of the transformation economy—as well as the ne plus ultra: coaches.

“Anything with a ‘coach’ in it,” he says. “Whether it’s a life coach, whether it’s a fitness coach, whether it is a tennis coach or a golf coach … All coaches are in the transformation business.”

There are over 1,000 life coach jobs listed on the US jobs website Indeed, where the share of life coach listings has more than doubled since early 2016. Life coaches are also among the fastest-growing categories for the local job marketplace Thumbtack, where they have increased by more than 60% each year. There are now about 5,000 active life coaches available on the site.

Marketdata estimates that self-improvement was an $11 billion market in 2018, and that personal coaching alone will be a $1.3 billion business by 2022. The Global Wellness Institute estimates (pdf) tourists spent about $90 billion on retreats and spas with wellness as the primary motivation (and some $550 billion more on wellness activities during their travels) in 2017. And the global market research firm Euromonitor projects that spending on luxury experiences will outpace spending on luxury goods for the next five years. So it stands to reason that brands want to get in on the transformation economy, whether by sponsoring running clubs, retreats, or mass meditations.

Goop, Gwyneth Paltrow’s wellness juggernaut, is part of the transformation economy. So is the second coming of the Esalen Institute, once a countercultural think tank for the likes of Timothy Leary, Alan Watts, Joan Baez, and Aldous Huxley, and today the grounds for soul-searching executives from Silicon Valley.

Many of those executives have invested in transformational services, too, either through one-on-one training, or by hiring high-profile coaches and speakers like researcher, author, and motivational superstar Brené Brown (whose cult status was recently spoofed in the Amy Poehler movie Wine Country) to train their employees. In the case of companies like Lululemon, that includes sponsoring employee immersions in programs such as the Landmark Forum, which promises “positive, permanent shifts in the quality of your life.” TOMS founder Blake Mycoskie recently told Inc. magazine about how his nine-day stay at the Hoffman Institute—a self-described “organization dedicated to transformative adult education”—helped him recognize a “vicious cycle” in his work habits. His wife also espouses its miracles to her 11,800 Instagram followers.

And it’s not just millennials with Instagram life coaches investing in personal transformation. Aging baby boomers—with their extra time and money—are also driving the shift. With his 2018 bestseller How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us about Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence, superstar author Michael Pollan, 64, has become a champion of psychedelics as a method for facing one’s own mortality.

“You get to that middle place [in life] and that which you take for granted might not be here tomorrow,” Andrea Lukens, a recent empty-nester who traveled from San Francisco to Los Angeles for a 2017 Goop summit with tickets ranging from $500-1,500, told me then. “It’s accepting responsibility for yourself and your body—and your journey.”

While many of the players in the transformation economy are new businesses leveraging recent trends, some companies have been at it for decades. Weight Watchers, now known as WW, has been selling transformation since its first meeting in 1963.

Why now?

“The desire for transformation is so off the charts,” Jan Birchfield, an executive coach and spiritual healer who founded the Antara Retreat in Taos, NM, said. “People are starving. In this last year, the pace at which we grew was startling, and I can feel it.”

Many factors have pushed personal transformations into the realm of capitalism—not the least of which is the progression of the US and other developed economies.

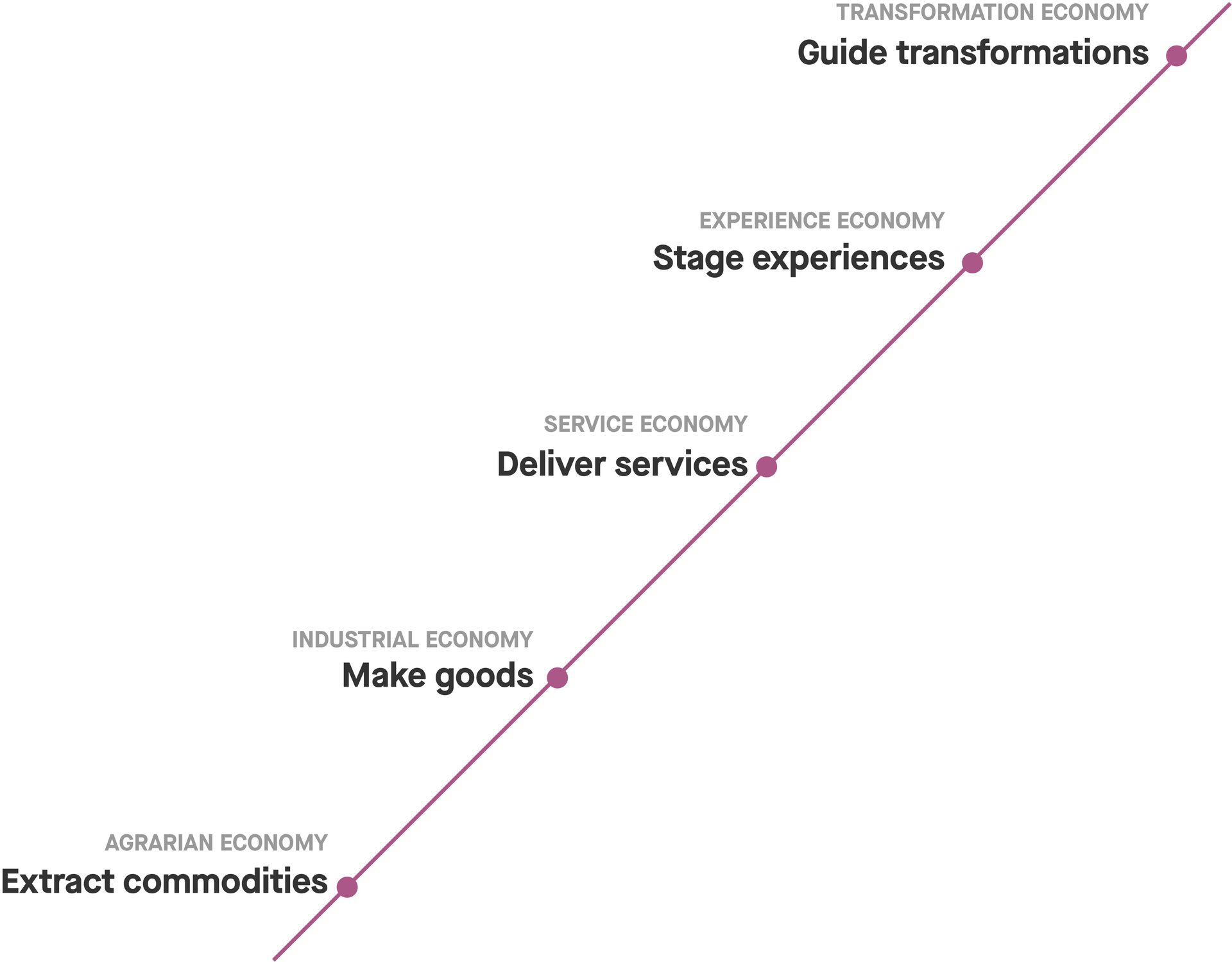

When the US was founded, its economy was primarily agrarian, based on the commodities we could grow and pull out of the ground. With the Industrial Revolution, value was added to those commodities and became an industrial economy based on tangible goods. In the latter half of the century, the US became a service economy, when activities done on behalf of customers overtook manufacturing. Now, Pine says, “we’ve shifted into an experience economy, where goods and services are no longer enough, and where we’ve got enough stuff.”

And as we increasingly Marie Kondo our closets and value our experiences over our possessions, we want those experiences to be not only enjoyable (and Instagrammable), but meaningful.

This search for meaning and connection is likely related to the rapid decline of religion in the US. A Gallup poll from July found Americans’ confidence in churches or organized religion has reached an all-time low. As Derek Thompson recently wrote for the Atlantic, many Americans, left without the sense of belonging a weekly congregation can provide, are looking to ease their “modern existential anxieties” elsewhere.

We are always on, and burned out—and many of us no longer find relief in religion.

“[Religion] is a bundle: a theory of the world, a community, a social identity, a means of finding peace and purpose, and a weekly routine,” writes Thompson. “Those, like me, who have largely rejected this package deal, often find themselves shopping à la carte for meaning, community, and routine to fill a faith-shaped void.”

And shop they do.

LVMH, the luxury goods behemoth, sees the writing on the wall. In 2018 the company acquired the hotel and tour operator Belmond and its 46 global properties, which offers experiences such as watching elephants visit a watering hole at dawn at a Botswana game reserve, boxing with Muay Thai instructors in Koh Samui, Thailand, and attending an offering ceremony with an Andean shaman in Peru’s sacred valley. Exclusivity and price tags would qualify these experiences as luxury—but if Belmond does its job right, they might even be transformative.

Nike is mainly in the shoe business but the company is tapping into transformations too, with its Nike Run Club app, which promises a “Nike coach” that starts with the runner’s goals and adapts as they progress. New York City marathon runners can even apply for Project Moonshot—a 16-week $262 training program that just wrapped up its third year.

Even Suzy Batiz, whose bathroom spray Poo-Pourri has given her an estimated $240 million net worth, says she is really in the transformation business: “I’m only about transformation,” she says. “That’s just what I do. That’s my whole life. I transform poop into smelling good.”

It makes sense that marketers are ready with lots of transformational opportunities. After all, there may be no higher compliment for a vacation—or a meal, class, or workout for that matter—than to call it “life-changing.”

“Once marketers get ahold of it, they can ruin any concept,” says Pine, adding that he steers the companies he advises away from using the word “transformation,” and instead toward “coaching” and “outcomes.”

Isn’t this all just wellness?

To be sure, there’s a lot of overlap between the wellness industry—with all its yoga mats, face oils, supplements, and spa treatments—and the market for personal transformations.

But while wellness is about achieving or maintaining an ongoing state of well-being, transformation is about aspiring to something beyond one’s current condition—whether that’s inner peace, rock-hard abs (and no back pain!), inbox-zero, or the confidence to speak up in meetings.

And part of what distinguishes a transformation (say, a silent meditation retreat) from a mere experience (a few days at a resort), argue Pine and Gilmore, is a focus on the outcome and the customer—or, in their parlance, the “aspirant.”

But selling personal growth is just one aspect of the transformation economy.

A new lens on business

There’s a significant business-to-business opportunity here too, says Pine, arguing that management consultants are among the earliest adopters of this new way of thinking about their services—and charging for them.

“You are what you charge for,” Pine frequently says, by way of determining which economy—industrial, service, experience, etc.—a company is participating in. For example, if you charge for tangible things, you’re in the goods business. If you charge for the activities your people perform, you’re in the services business.

And you’re only truly in the transformation business, says Pine, if you charge for outcomes. A global consulting firm like Bain & Company might charge for increased market capitalization resulting from its services. Similarly, some US universities now offer income sharing agreements, or ISAs, which are essentially student loans to be paid back as a percentage of one’s annual income.

Of course, this sort of model is rare among life coaches or personal trainers, who typically charge for their time (and are by Pine’s definition therefore in the experience business). But Pine argues that as these experiences become more common and less differentiated, the people providing them should think in terms of transformations. All of which is to say, they should consider their clients’ desired personal outcomes—their aspirations—and if possible, to charge for them. At the very least, they should promote them.

We see this in the rise of ballet-inspired barre classes, which are uniquely results-driven, with excruciating micro-movements designed to achieve taut arms, strong abs, elevated buns, and lean legs. No one does these classes because they’re fun or therapeutic.

From a consumer perspective, the transformation economy represents a slightly different way of thinking about how we spend our time, and our money. Oftentimes, we want our goods and services as cheaply as possible (thanks, Amazon!), so we can spend our money on experiences that we value. The metric for valuing experiences, says Pine, is whether we consider them time “well-spent.” The metric for transformations, he says, is time well-invested.

“I’m investing this time right now to pay benefits now and into the future. So it’s the compound interest of that time,” says Pine. “When it’s the transformation, it’s even more valuable than it is with an experience.”

What are we all aspiring to?

Beyond taut arms? Self-actualization, which is to say, the full realization of one’s personal potential. This, of course, is not a new idea—but charging for it is.

When the Esalen Institute, arguably the epicenter of the transformation economy, was founded in 1962 on an astonishing stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway in Big Sur, California, it was deeply countercultural. Esalen, which is still run as a non-profit, didn’t establish a single spiritual or philosophical leader, but instead hosted a variety of radical thinkers that included Abraham Maslow, Ida Rolf, and gestalt therapy founder Fritz Perls to study there, and lead lectures, seminars, and workshops. Their commonality was what was then called the Human Potential Movement, which Calvin Tomkins described in 1976 as a “somewhat amorphous but rapidly growing effort to tap unsuspected resources of energy or perception or sensory awareness in all of us.” In other words, self-actualization.

Esalen is a spectacular 27-acre property with cabins, gardens, and tubs fed by natural hot springs overlooking the Pacific. In accommodations ranging from shared floors with sleeping bags ($675 for 5 days) to private double suites with oceanfront verandas ($6,252), it today hosts some 20,000 visitors—or “seminarians”—for workshops including “The Transformational Enneagram,” “Come As You Are: Transform Your Sex Life,” “The Neuroscience of Resilience,” and “Relational Gestalt Practice.” (It also inspired the hippie-laden lawn where Don Draper has his Coke-ad epiphany in the finale of MadMen.)

Over two espressos on a recent Sunday morning in Los Angeles, Esalen CEO Terry Gilbey told me that today, as in 1962, Esalen is still working to maximize human potential—but that means something slightly different in 2019.

In an age when technology makes all constantly on and available, he said, this chapter of the human potential movement focuses less on potential and more on just being human.

“How do we connect as humans? That is probably what I hear and witness as the most fundamental impact we begin to have,” says Gilbey. “It is around connection over connectivity… In our greater isolations of time, resources, polarization, environmental challenges, technology, we are missing that human piece.”

Today, Esalen’s proximity to Silicon Valley situates it as a close refuge for those responsible for much of that connectivity. A recent New Yorker story described an invitation-only weekend in 2016 for high-level tech executives from companies including Facebook, Slack, and Tinder to retreat and convene.

“I didn’t spend a lot of time in the hot tub—I got more out of just talking to everyone, honestly and openly, without us being distracted by our phones,” a co-founder of a mobile app told the New Yorker. “Afterward, I started thinking, Maybe our goal should actually be less time on the app … Maybe the best way to serve our customers is to get them off the phone, building relationships in the world.”

Esalen has a history of this sort of soft-power influence, or what was called “hot tub diplomacy” after the institute organized a series of US-Soviet meetings in the 1980s, hosting diplomats, psychologists, astronauts, scientists, KGB agents, and ultimately, Boris Yeltsin on his first trip to the US.

When I asked Gilbey—who took over as Esalen’s CEO in 2018 after former Google product manager Ben Tauber held the post for just over a year—about the institute’s current relationship with the power players of Silicon Valley, he said it remains focused on transformation from within.

“We are just on the doorstep of Silicon Valley. It’s obviously an area that is incredibly impactful to humanity at the moment globally,” he says. “The question is, in my mind, less about necessarily trying to change what happens externally, but more about how do we change internally.”

Though increasingly, consumers are looking externally for help with that change.

What could go wrong?

With handing our self-actualization over to profit-seeking corporations? Nothing!

In all seriousness, Pine says the transformation economy is predicated upon companies—whether mega-management consultant firms or life coaches working from home—asking themselves about consumers’ aspirations. So an obvious risk is that rather than orienting their actions to achieve their customers’ goals, they’ll think instead about their corporate ones.

“Companies may try and infiltrate into a transformation what they want you to achieve, not what you want you to achieve.”

Pine says this happens all the time with the businesses he advises. He’ll ask them to note customers’ aspirations and they write something like, “become loyal customers.”

“It’s like ‘no, no, no, no.’ That’s what you want. Who cares from the consumer perspective? What do they want?” he says. “If you do a good job of giving them what they want, they will become loyal customers. But that’s not the aspiration that they are seeking.”

“I drank the Kool-aid for a while”

Take Becca Walters, a 32-year-old SoulCycle instructor and tour guide in New York City. Walters said she had initially been thrilled with her experience with the Landmark Forum in January. Landmark, founded in 1991, is based on Werner Erhard’s EST (Erhard Seminars Training)—an early and controversial piece of the human potential movement that included intensive weekend seminars akin to a boot camp for the mind, yelling included. (If you watched The Americans, you may remember when Philip got into EST.)

Walters described her Landmark experience as “a weekend of group collaborative coaching” with about 160 other people in New York, which she attended after one of her regulars at SoulCycle, who had become something of a mentor, signed her up and covered the cost on her behalf.

“At the time, it was great for me. That whole idea of being present, and just taking in what’s right in front of you, I definitely learned that from them.” But in the years since, she said she’s been disappointed by the company’s recruiting practices.

“I drank the Kool-aid for a while after, but it’s just become very, very diluted. The follow-up has made me feel a little turned off by how pushy they are … I’m very disheartened by how much they call me and tell me that I have to sign up for the next course,” she said. “Their follow-up goes exactly against who they are and therefore put a really bad taste in my mouth.”

Landmark says it has had 2.4 million customers, and most of them are pleased. “We regret to hear that any of our customers were left with anything less than an exceptional experience,” the company said in an emailed statement.

It was partially Walters’ training as a professional coach—she completed two of four courses in a coaching program at New York University’s School of Professional Studies—that helped give her the confidence to leave Landmark behind. When NYU announced that it would be discontinuing her program and instead offering a masters degree in coaching, Walters decided it was time to take a step back from all the transformational training.

“Here’s what I really think is the bottom line about all this transformation stuff. I think it’s way too saturated, and what’s happening is people are no longer able to trust their own abilities.” she said. “I spent a lot of time trying to add, add, add, add, add—add knowledge, add jobs, add relationships, and now I’m just at a place where there’s too much adding. I can’t read any more books. I can’t take any more classes. I need to just sit back, and actually let my life happen.”