Don’t use the language of criminal law for a constitutional process like impeachment

The impeachment inquiry into president Donald Trump’s Ukraine dealings has spawned much discussion of the US Constitution. But all the talk has also given rise to some confusion about what exactly impeachment is and what it is not.

The impeachment inquiry into president Donald Trump’s Ukraine dealings has spawned much discussion of the US Constitution. But all the talk has also given rise to some confusion about what exactly impeachment is and what it is not.

Impeachment is a constitutional process. It is not a criminal proceeding. While there are similarities between the two, they are not the same, and critical distinctions are being overlooked by Democrats and Republicans alike for different reasons.

Democrats emphasize criminality because they believe only evidence of the commission of a crime will convince the American people Trump must be removed. Take, for example, a recent “plea from 33 writers” in the New York Times, urging journalists to articulate carefully because “words matter.”

They write, “Please stop using the Latin phrase ‘quid pro quo’ regarding the impeachment inquiry. Most people don’t understand what it means, and in any case it doesn’t refer only to a crime. Asking for a favor is not a criminal act…Please use words that refer only to criminal behavior here.”

Apart from erroneously assuming that reporters are arguing the case for or against impeachment—rather than relaying information that is relevant to understanding the facts and process as it’s happening—this effort to correct actually leads everyone astray.

Presidents can’t be criminally prosecuted in office

Trump can be impeached and removed from office in this process, but he can’t be convicted of a crime as president. That is why, previously, special counsel Robert Mueller said he couldn’t charge Trump with obstruction of justice in relation to his investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 US elections. He presented the evidence to Congress for lawmakers to decide how to respond because impeachment is not initiated by prosecutors, technically.

More importantly, to be impeached a president doesn’t have to commit a crime specified in a statute, unlike in criminal law, which is highly specific in its enumeration of offenses and the elements that must be proven for a conviction. Impeachment lets the government investigate and remove corrupt officials. But there’s no list detailing precisely which offenses qualify for this process.

For example, the founding fathers discussed and discarded the term “maladministration”—James Madison thought it was too vague. Meanwhile, Gouverneur Morris, a Philadelphia representative at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, started out opposed to executive impeachment altogether but ended up convinced that the clause should actually be expansive to capture a wide range of potential presidential wrongdoing, including “corruption, treachery, incapacity, and other causes.”

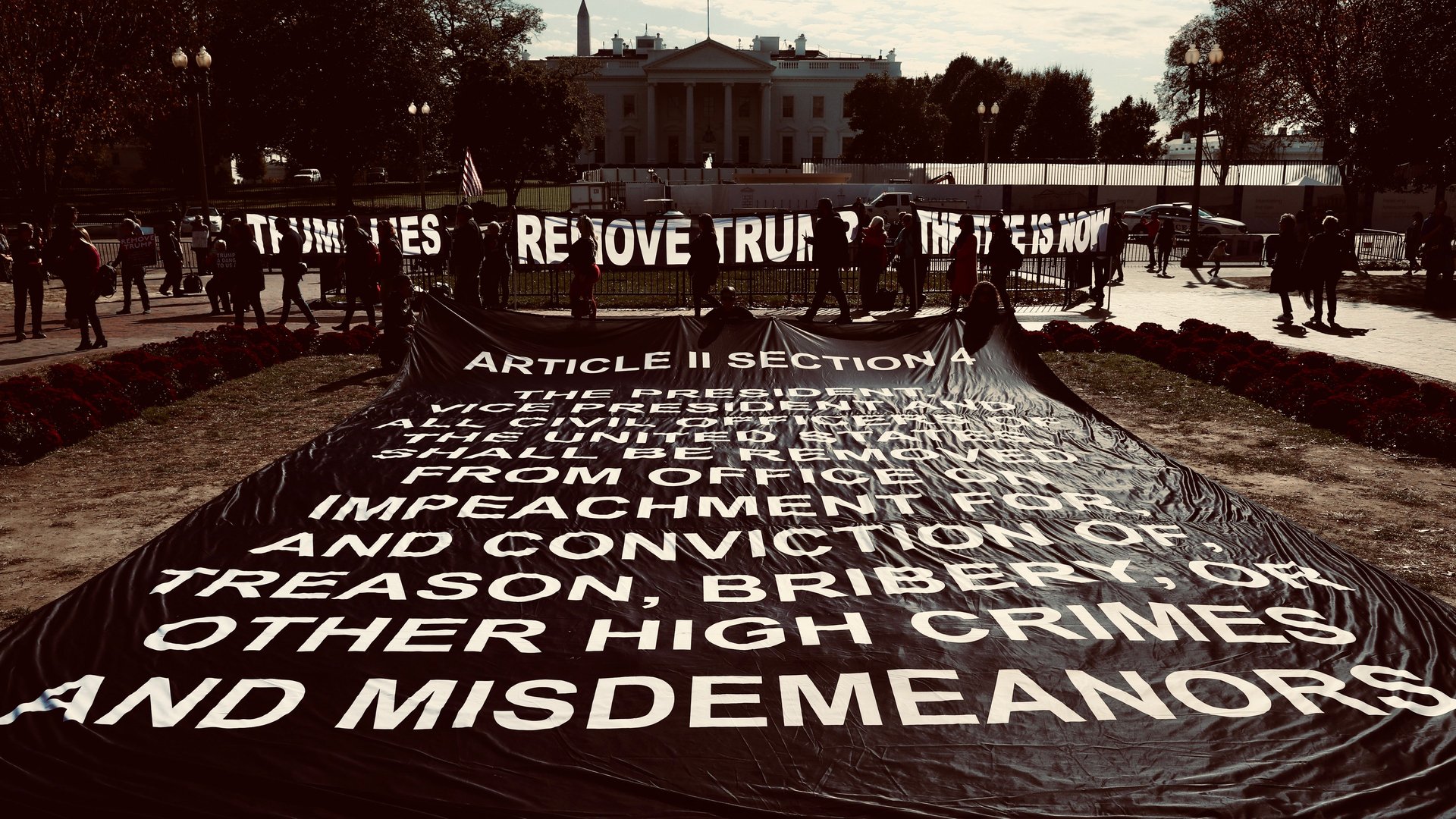

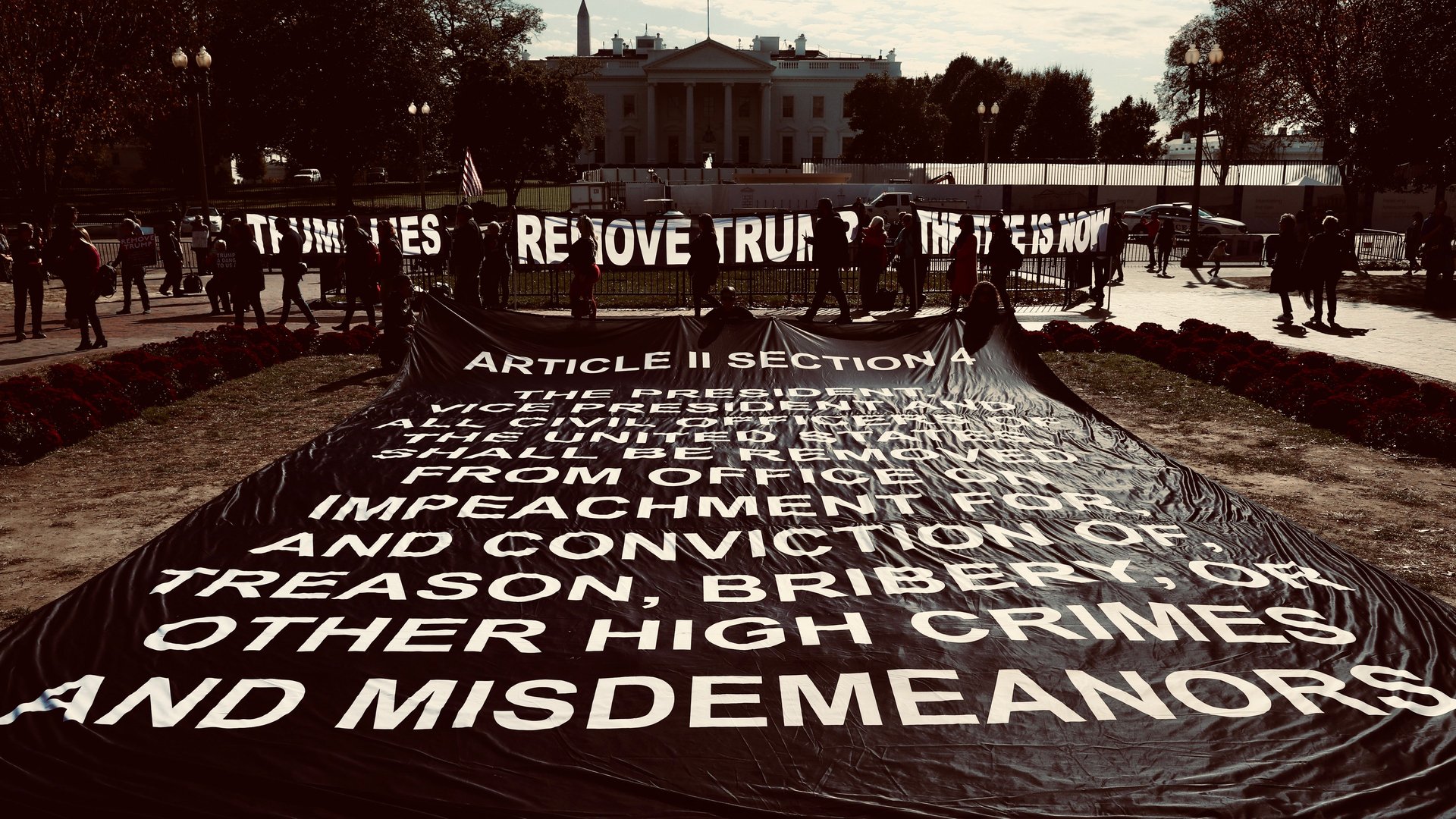

The final version of Article II, section 4, of the Constitution provides:

The President, Vice President and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

As a leading member of the final constitutional style committee, Morris even secretly slipped in a small update to the final version of the Constitution that went unremarked upon and ended up ratified. William Treanor, dean of the Georgetown University Law Center and author of an epic paper outlining Morris’s linguistic treachery, argues that the “Scrivener of the Constitution” removed the words “against the United States” from the end of the impeachment clause to ensure that the executive could be removed even if his offense was not governmental but personal.

Impeachable offenses haven’t all been enumerated

Since 1787, debate about what exactly counts as impeachable has raged. And the answers are still not obvious.

Presidential impeachment doesn’t happen often, and the Constitution doesn’t provide total illumination, which means we don’t yet know all the offenses that might qualify. However, constitutional law scholars generally agree that “misdemeanors” in the clause doesn’t refer to petty offenses in the criminal law sense, but rather to any kind of serious malfeasance that interferes with presidential duties or endangers the nation’s interests.

The one thing that isn’t seriously disputed—but is widely misunderstood and subject to spin—is the fact that impeachment isn’t a criminal process. While the president can be subject to the typical criminal proceeding for actions that are also impeachable after he’s out of office, impeachment is merely a mechanism for governmental censure. It doesn’t threaten life or liberty, like conviction for a crime, and is therefore much less severe (although, of course, it is also deadly serious). The process exists to protect citizens and the government from bad actors more than to punish them.

Yet Republicans adopt the language of criminal law because the bar for conviction is extremely high and requires proof of “state of mind,” an intent to commit a crime. By resorting to linguistic tricks, they can admit that Trump may have done wrong but that he did not mean to and, as a result, isn’t guilty. Emphasizing criminality thus helps the president’s supporters diminish the import of his actions.

It also allows them to decry the impeachment inquiry as unjust for failing to follow the rules of a criminal investigation and depriving the president of due process. These claims are disingenuous because the process undertaken by House Democrats does conform to constitutional requirements but the complaints create confusion for Americans attempting to make sense of contradictory arguments from the right and left.

Indeed, it sometimes seems the one thing Democrats and Republicans have in common when it comes to the impeachment process is this mistaken understanding. While criminal process makes for a convenient analogy to explain the president’s predicament, it’s not a perfect fit and, most critically, isn’t entirely accurate.