Rich-world megatrend: older workers are keeping the young out of jobs

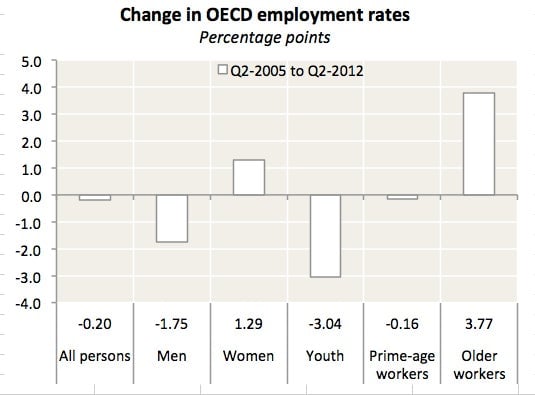

While unemployment has soared in Europe and elsewhere, at least one group has weathered the unemployment crisis fairly well: older workers.

While unemployment has soared in Europe and elsewhere, at least one group has weathered the unemployment crisis fairly well: older workers.

Then again, that may be a bad thing.

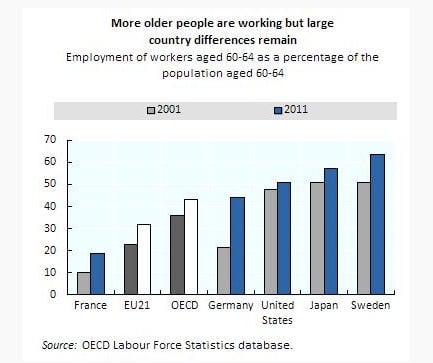

The percentage of people over 60 in the workforce has climbed steadily over the past decade. Partly it’s about 60 being the new 50, but it’s also about rising costs of living, a lack of savings, and people clinging to jobs out of fear over disappearing pensions. Between 2001 and 2011, the employment rate for people between 60 and 64 years of age in OECD countries increased to 43.1% from 35.8% (chart below). For people between 65 and 69, it rose to 22.8% from 17.5%, over the same period.

This spells bad news for young people. Already it’s been a brutal last seven years for them in which the job market has been particularly unkind.

Young people are increasingly nervous about their future, as you might have noticed over the past year from the Occupy protests and the young people rioting in Greece and Spain. A survey by One Young World, an international activist youth organization that’s currently meeting in Pittsburgh, found that just 30% of young people in Europe and the US believed they would enjoy a better quality of life than their parents. By contrast, 72% of young Chinese and 69% of young Brazilians were confident of a brighter future. Both Brazil and China have low unemployment rates.

In Europe, the situation is pretty bleak. While unemployment rates for under-25s in some European countries top 50%, employment rates of the over-60s have boomed. In France, the employment rate for people between 60 and 64 has nearly doubled over the past decade. It’s the same story in Germany, while the rate has more than doubled in the Netherlands and tripled in the Slovak Republic.

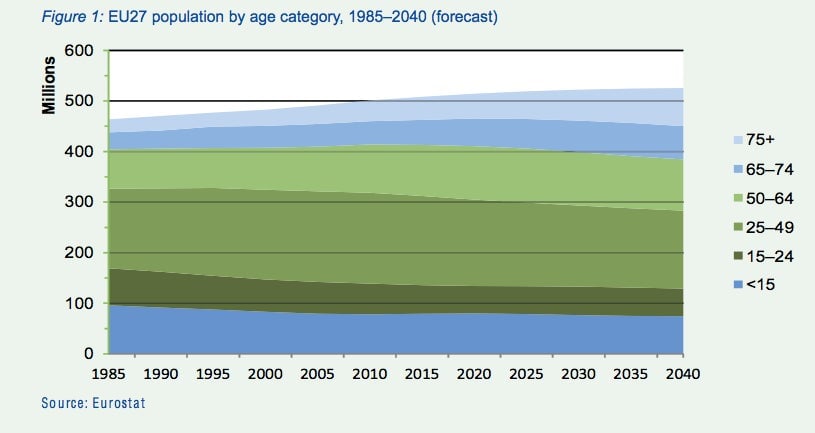

Partly explaining the surge is the fact that societies in Europe are aging. The number of working-age people (15-64) peaked in 2010-2011. Meanwhile, the number of people aged 65 and over is expected to increase 20% (PDF, page 1) by 2020.

This is all fuel for the argument—which the OECD itself has been making—that rich countries need to raise their retirement age. As the figures show, retirement ages are rising by themselves. Recognizing that reality would allow countries to start paying out retirement benefits later, and plug some of the frightening fiscal deficits that contributed to the lack of jobs in the first place.